During the time of the coronavirus, many ordinary activities suddenly seem quaint. Can you imagine being fitted for a suit right now or sampling a bottle of wine at a swanky restaurant? By the same token, many of the works of fiction that were released at about the time the pandemic took root in America have also acquired a musty, instantly dated vibe. What sort of world are they describing? Not ours — at least not right now.

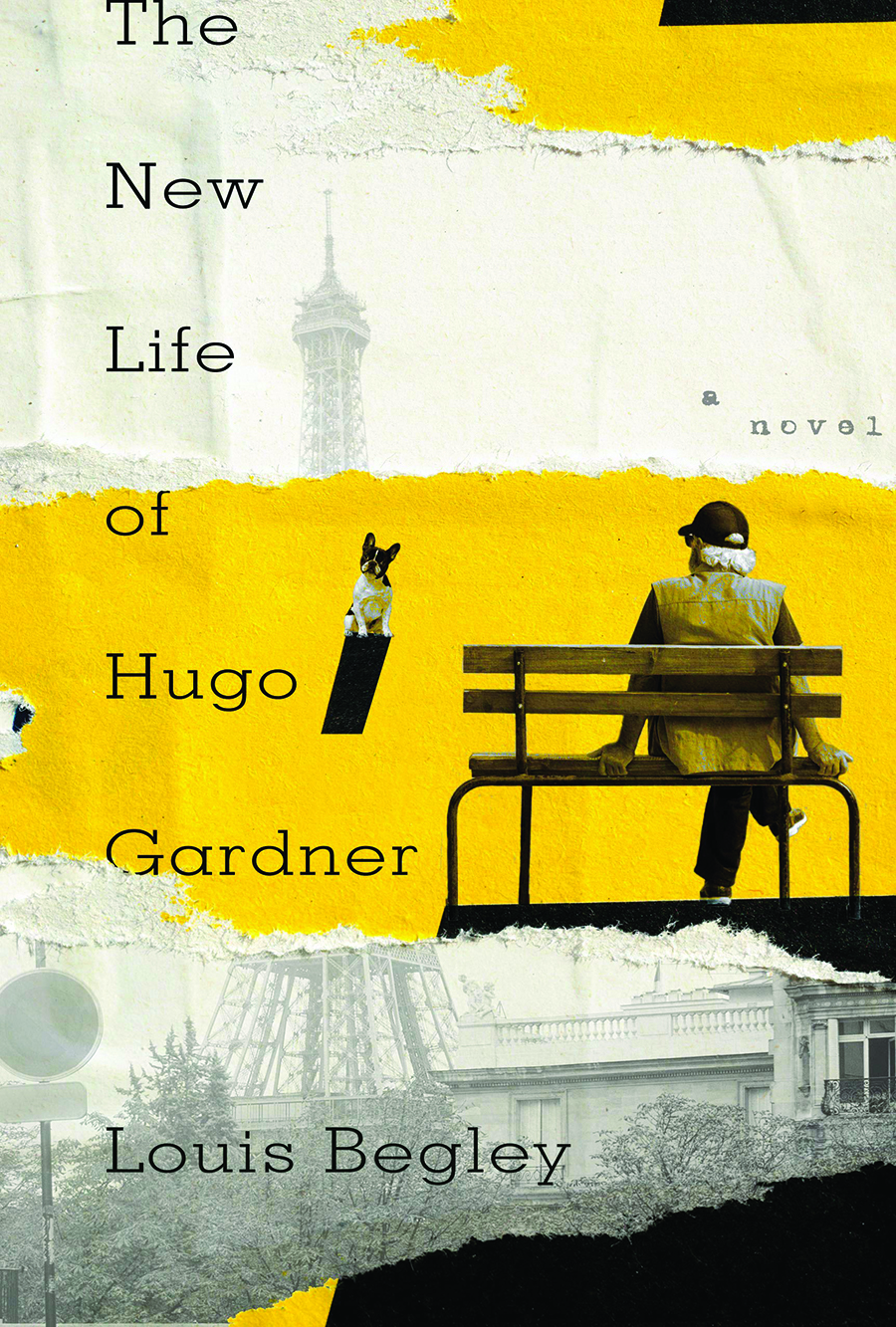

Happily, Louis Begley baked an intentionally old-fashioned quality into his elegant, companionable new novel, The New Life of Hugo Gardner. Indeed, the latest work by the 86-year-old author of Wartime Lies and About Schmidt would likely have read as fairly crusty even if it had been published prior to the pandemic.

For starters, although the novel unfolds during the 2016 presidential election, Begley makes use of certain signifiers of success and status that no longer pack the punch they once did. The novel revolves around the late-in-life romantic angst of 84-year-old Hugo Gardner, who, in the novel’s opening pages, receives word that, in what he perceives to be a supreme act of unmotivated churlishness, his wife of many decades, Valerie, is seeking a divorce.

Yet if this bombshell crushes Gardner’s sense of self-worth, it isn’t obvious from the carefully worded first-person narrative. You’ve heard of the unreliable narrator? Begley gives us the full-of-himself narrator. To be sure, Gardner has the sort of social credentials that, a generation or two ago, would really have counted for something. He informs us that his great-great-grandfather and great-great-uncle were both bishops in the Episcopal Church, and his father a partner at the investment bank Morgan Stanley. Gardner’s own chosen profession, following his obligatory college career at Harvard and two-year term in the Army, is comparatively down-market. Attracted to the “glamorous new Time-Life Building” and seeing an opportunity to make use of his “fluent French, learned at school and polished to a high sheen during the Fontainebleau years,” Gardner is installed at Time magazine, where, over the course of a long and satisfying career, he has ascended to such lofty heights as bureau chief in Paris and, eventually, managing editor.

Rather pitiably, Begley has the long-retired Gardner make endless references to his adventures in journalism at what was once the toniest of the major weekly news magazines. At one point, Gardner ponders how one of his two children with Valerie, his son Rod, currently employed at a relatively lowly law firm, could have done better given his top-notch family pedigree. “The fact that my father had been a leading partner at Morgan Stanley and that I ran Time, a position generally considered one of influence if not power, would not have been disregarded.”

Begley, whose literary career kicked off while he was still active at the law firm Debevoise & Plimpton, clearly delights in evoking his hero’s cultivated milieu. This is a book in which the narrator casually tosses off one high-flown cultural reference after another. At one point, he speaks of listening to an audiobook version of Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, comparing Valerie to that novel’s traitorous wife, Brenda Last. The book has lines like this: “The story begins in New York, in 1977, at a Council on Foreign Relations meeting for Cy Vance, to which someone brought as a guest a Paris Match colleague, a correspondent dividing his time between the city and D.C.”

Gardner may be a man of exquisite, if easily parodied, tastes, but when it comes to the women in his life, he finds himself in a state of perpetual mystification. He expresses bafflement at his estrangement from not only Valerie but also his daughter Barbara. “I was bewildered by her behavior, unable to recall when, or through what action or inaction, I had so offended her,” Gardner says. Strikingly, no serious attempt is made to unravel any of the characters’ grievances against him. That includes Valerie’s decision to forsake her husband for a wet-around-the-ears restaurateur, which is merely treated with amusing derision. Equally inscrutable is Jeanne, a chic French woman from Gardner’s past with whom he rekindles a romance following his divorce. Echoing novels by several of his now-deceased peers, including Philip Roth and John Updike, Begley writes with abandon of his elderly protagonist’s love life, resulting in some purple passages in his otherwise peerless prose.

Yet Begley’s decision to limit the novel to Gardner’s perspective confirms our impression of him as a man whose time has come and gone — a relic, an artifact. This is why the references to his antipathy for both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton seem so jarring and weirdly out of place. It’s like listening to a figure as ancient as Elliot Richardson inveigh against the contemporary political scene.

In fact, the novel is at its weakest when Gardner delivers various screeds against the Right, including what he imagines to be Republican voters’ nostalgia for a nonexistent past: “The mortgage on the one family house the family lives in has been almost paid down; the shiny Chevy in the driveway is owned free and clear,” Gardner says, condescendingly. But surely, Begley intends to present Gardner as the king of nostalgia: for the excitement of his time at Time, for the ardor of past love affairs.

It isn’t a new life that Gardner seeks but his old one, and all of its urbane accouterments.

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including The Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Humanities.