More than once, while reading Indigo by Padgett Powell, one of America’s greatest living writers and sadly a certifiable unknown to most of the reading public, I had the urge to stand up from the corner couch of my local coffee shop and slap away the book from the unenlightened reader sitting across from me. “This,” I’d say, holding up my advanced copy of Indigo, “is what you should be reading. Padgett Powell is one of the last ones left!” Thankfully, I was able to restrain myself and resume the very sane behavior of maniacally cracking up after every third sentence and muttering to myself, “That Powell, boy, he’s straight-up nutso.” You could say I was possessed by Powell’s prose, which is the response he induces in his cultish admirers, a collection of writers and deranged readers who’ll tell anyone who’s had the misfortune of being cornered by them at a literary event or bookstore that Padgett Powell is an old-school American genius.

So, who is he? Let’s get the necessary biographical information down first so we can proceed to what matters. Padgett Powell is a 69-year-old man from Gainesville, Florida, who’s written seven novels, three short story collections, and a lone essay collection, the long-awaited Indigo. He taught for over 30 years at the University of Florida and has influenced such literary luminaries as Ben Marcus and Sam Lipsyte, which has earned him that dreaded label of writers’ writer. The truth is that Powell is far too good, far too stylish, far too wacky, and certainly far too American to have achieved anything but cult status. But his 10 books, written in his idiosyncratic style, a hysterical Southern gothic mashup of pathos and hijinks, are singular literary creations and the work of a beautiful weirdo the likes of which are nearly an extinct species in the literary world.

Powell, who flamboyantly showed up on the scene in 1984 with Edisto, a hilarious debut novel narrated by a 12-year-old with the wit and vernacular of a Southern dandy triple his years, has mined Southern strangeness with great success going on 40 years now, but Indigo, a delectably all-over-the-place collection of nonfiction, might be his best yet. To the cultists, Indigo will be catnip and further proof of Powell’s greatness, but the uninitiated will encounter a writer of almost incomprehensible style and masculine swagger, a combination today’s woke readers prone to wilting at the slightest aggression might not know what to make of. Powell’s literary type has all but been banished, so it’s a miracle, really, that this book, collecting rough and rowdy tales of an older and weirder America, even exists, and it will be fascinating to see how an elite literary readership groomed to resist this sort of thing will respond to it.

The opening piece, “Cleve Dean,” one of several standouts in Indigo, finds Powell profiling “a farmer and a pulp wooder who disappeared from the sport of arm wrestling for nearly ten years after being on top of it for eight,” and begins: “Against its reputation as a pastime of drunks, against the notion that it is stupid, arm wrestling does most efficiently what sport is asked to do, which is translate the muddle of success and failure in life into something knowable: who wins and who doesn’t and why. In these terms, arm wrestling looks consummately elegant, the locked jaw and the grunting sublime. Your arm, your will, and victory or loss.” This passage contains more truth, style, and grit than most of what passes for literary fare today. And yes, grit matters, as any of Powell’s rabid fans will attest.

In “Cleve Dean,” Powell positions himself in his usual role of foolish genius, a character with amazing verbal dexterity and endless curiosity, even love, for the kooks and freaks he seeks out and profiles. This narrative style has no use for lifeless elite spaces chock-full of affectation and irony. Powell heads to Stockholm with an overweight arm-wrestling legend looking to reclaim his throne and shows just how easy it is to be pulled into the story of someone who isn’t paralyzed by crippling self-awareness.

In “Spode,” Powell profiles his beloved dead dog: “Here’s the deal: dogs like this one are not afraid of anything, and men afraid of things, as I am (of everything), take great solace and cheer from being just near that which is not afraid (and if that which is not afraid loves you, it will haunt you the rest of your fearful life).”

Indigo is a wonderful retrospective of Powell’s obsessions, but it also shows a glimpse of what the writing life was like back when literary writers didn’t have to moonlight as pundits or cultural critics and feign interest in political matters. The modern take artist still clinging to literary pretensions will shudder with jealously when Powell bums around New Orleans on a writing assignment that apparently required of him nothing more than drinking and chasing down some gumbo, another of the writer’s favorite topics. There is even a pieced titled “Gumbo,” which, unsurprisingly, is part love letter to the Cajun delicacy and part cookbook. When Powell goes into the history of gumbo, as well as his own personal history with the dish — “I found out what gumbo is and have been making it for thirty-five years” — one thinks, “Writers used to get paid for this!” In addition to the all-important gumbo, Powell tackles the squirrel, “a majestic creature, superior to your athleticism and to your wits on your feet,” in the aptly titled, “Squirrel,” and which lays a strong claim to be the greatest piece of literature about a rodent.

These playful, hilarious pieces are crucial representations of Indigo’s spirit and ethos. Powell shows the tremendous potency of writing about culturally insignificant topics that are nonetheless close to one’s heart; to many of us, this is the writing that truly matters. It’s hard to imagine anything with less potential for virality than gumbo or a squirrel, but in the hands of a master like Powell, these trivialities are elevated to the transcendent.

Indigo isn’t merely a love letter to the fertile soil found in the hidden corners of America but also to Powell’s favorite writers and mentors. It is rare to see a writer talk earnestly and even emotionally of his literary forefathers, but in the second-to-last piece in the collection, in which Powell breaks down at a reading of the aging Southern literary giant, Peter Taylor, “the kind of writer one discovers by overhearing better-known writers talk about writers,” one gets the sense he isn’t only getting emotional over a short story but preemptively mourning a literary landscape that was already on its way to disappearance. The other writers remembered in Indigo are Don Barthelme, Flannery O’Connor, Grace Paley, Denis Johnson, and William Trevor, all of whom are dead. But Powell remains. He is the last one left.

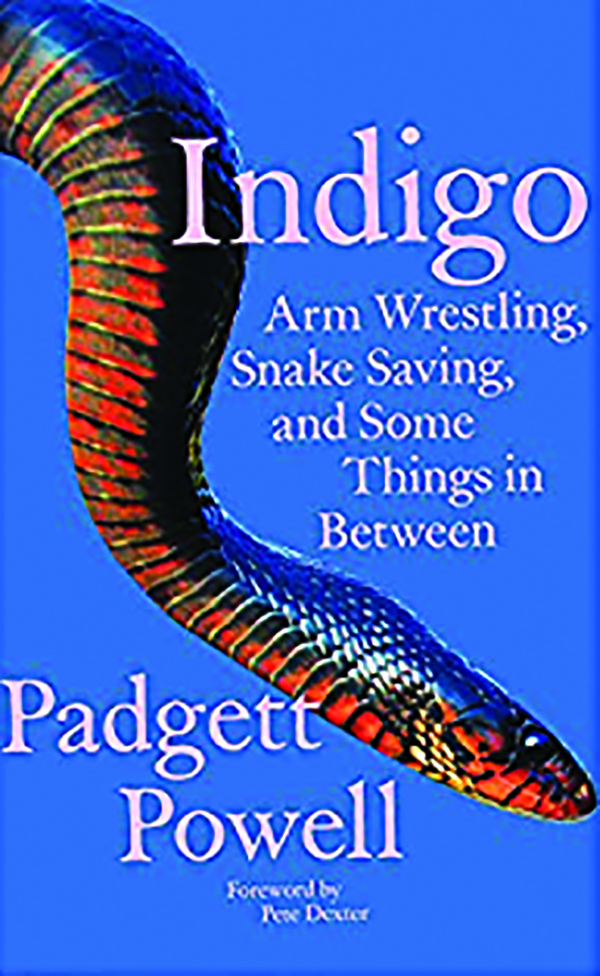

The book ends, fittingly, with Saving the Indigo, in which Powell is searching for the indigo, “a thinking snake” he encountered for the first time in 1964 as a 12-year-old boy but is now a protected species and nearly impossible to see in the wild. In his quest to find and hold a wild indigo, Powell traverses his home state of Florida, meeting with fellow snake obsessives and conservationists, until, finally, his moment comes without much fanfare, “the snake crawling right to him” when he least expected it: “And I see that I have a style: I will not rush an indigo snake if I do not have to. You do not knock the door down and handcuff a reasonable man. You ask him to come into the station, and he will.” Padgett Powell does indeed have a style, one that has always been rare and is getting rarer. He is a slippery snake of a writer, reappearing from the mossy crevices to remind us when we least expect that he is still around, still writing.

Alex Perez is a fiction writer and cultural critic from Miami. Follow him on Twitter: @Perez_Writes.