The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, presents the work of a complicated man. Caeiro was born in Lisbon in 1889, but he spent most of his life in the countryside. He received almost no formal education, but he was a passionate poet. At 25, he died of tuberculosis. Looking back, we can only be sure of one fact regarding Caeiro: He did not exist.

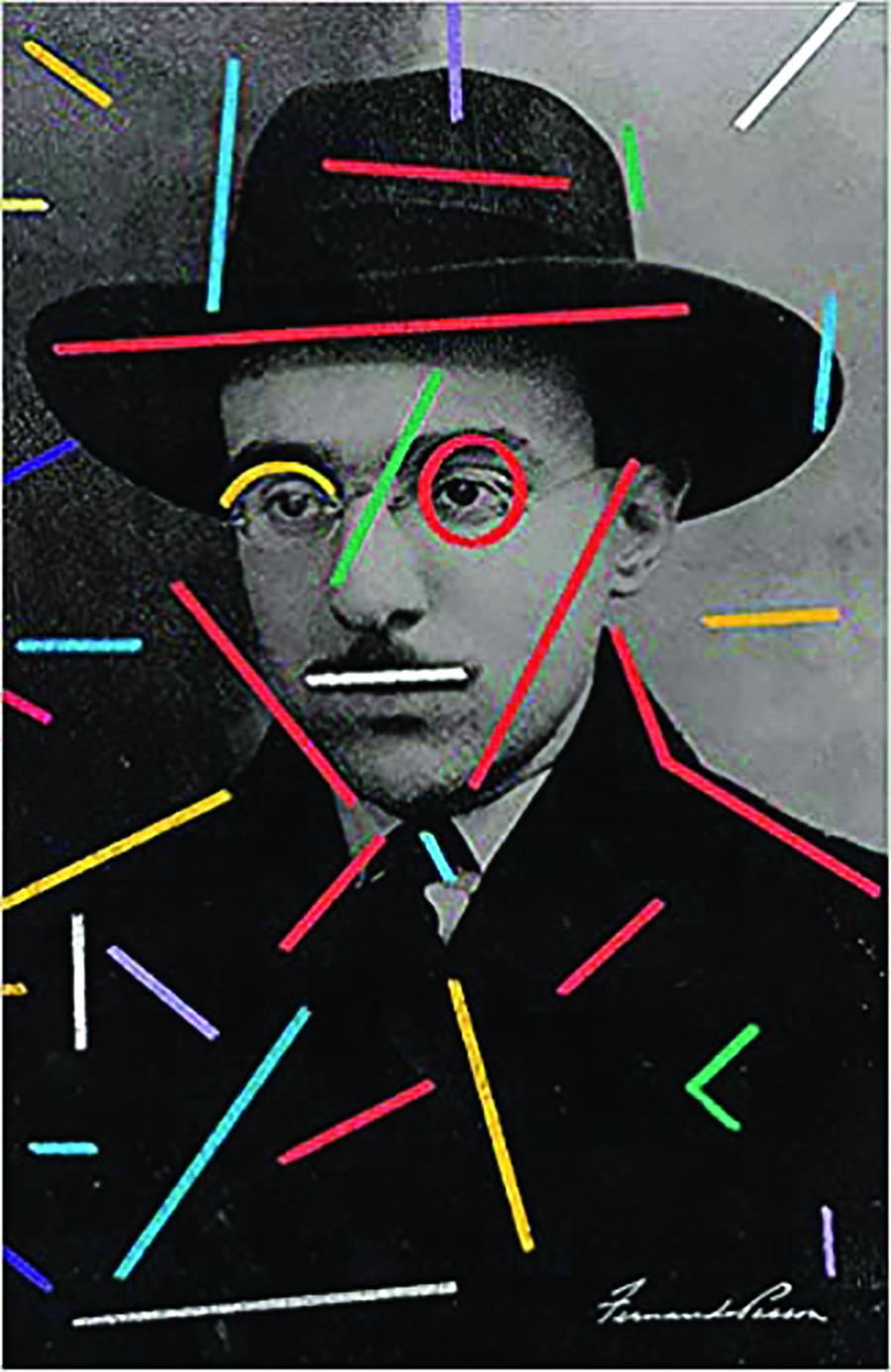

Or, more accurately, he was a fiction. A Portuguese poet named Fernando Pessoa made him up. Pessoa was an odd bird, a flaneur who haunted the cafes of early 20th-century Lisbon, sipping wine, scribbling poems on napkins, and leading dozens of lives between his ears. If his literature has a central precept, it is that there is no such thing as a stable, central self.

As if to prove it, he invented 72 literary personae, calling them heteronyms to emphasize their autonomy. As Pessoa explained, “[Heteronyms] are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own, with feelings I do not have, and opinions I do not accept. While their writings are not mine, they also happen to be mine.” Each heteronym had a detailed family history, a plausible personality, and a literary style Pessoa labored to make distinct, though they all share Pessoa’s penchant for metaphysical bluntness. They collaborated, feuded, and met in the street.

Among the 72 heteronyms, three predominated: Alvaro de Campos, the explosive futurist, Ricardo Reis, the gloomy Epicurean, and Caeiro, the shepherd poet revered by all the other heteronyms, who called him “master” and “genius.” Caeiro was Pessoa’s favorite. He claimed Caeiro visited him as though in a vision.

Pessoa kept most of this a secret. Though he helped bring literary modernism to Portugal in the 1910s and earned the respect of Lisbon’s intelligentsia, few guessed the ambition of his project. He published only a few books of poetry during his lifetime, and these to scant acclaim. To the eyes of strangers, he was a dapper nobody. In the eyes of literary acquaintances, he was a shy modernist, a fitful poet, and a drunk. He died in 1935.

After his death, a trunk was discovered in his apartment crammed with 25,000 scraps of paper. They included a hodgepodge of poems, astrological charts, and prose, signed by the various characters of Pessoa’s teeming imagination. The oeuvre is so vast, and Pessoa’s handwriting so poor, that scholars are still deciphering it. Every time a new edition of Pessoa’s work emerges, it is fatter than the last.

The latest of these editions to appear in the United States, The Complete Work of Alberto Caeiro, is a big book, fattened by facing page translations and reinforced with Pessoa’s prose on Caeiro. Thoroughness is one of its main virtues. If you want to understand Pessoa’s most famous heteronym, this book is a good place to start.

On the surface, Caeiro is a simple shepherd poet, ignorant and unliterary. You might get the impression of a bucolic man made happy by simple pleasure, but this would be misleading. Pessoa was obsessed with artifice, and Caeiro is his most strenuous pose. Though Caeiro’s poems are rudimentary in vocabulary and syntax, each stanza packs a philosophical punch. His message is fairly simple:

The only hidden meaning of things

Is that they have no hidden meaning at all.

It is stranger than all strangenesses,

Than the dreams of all the poets

And the thoughts of all the philosophers,

That things really are what they seem to be

And there is nothing to understand.

Pessoa called Caeiro’s work “a vaccine against the stupidity of the intelligent.” Rocks are rocks, trees are trees, and that is how it should be. Human beings would be better off if we had not been cursed with the ability to think. Caeiro wants to see without thinking; thinking he dismisses as “a sickness of the eyes.” He has nothing but scorn for other poets, who write about “what isn’t there.” Perhaps the most shocking thing about Caeiro’s work is its rejection of metaphor, which is the bedrock of poetry. A poet, you might say, is somebody who shows you that X is Y:

The poets say the stars are … eternal nuns

And the flowers devout penitents for a single day,

But … after all, the stars are just stars

And the flowers are just flowers,

Which is why we see them as stars and flowers.

Caeiro repeatedly tells us that X is not Y. X is just X, and only an idiot would say otherwise. In a sense, Caeiro tries very hard not to be a poet, and the resulting poems are skeletal but strangely alluring. There are almost no sensory details. He will tell you he’s looking at a tree, but he won’t describe it. He claims to scorn thought, yet his stanzas are cerebral and rigid.

Translators of Caeiro have their work cut out for them. How can you capture the spirit of a grumpy anti-poet who doesn’t believe in metaphors? We want translations to be beautiful, but in a letter to a friend, Pessoa admitted, “Caeiro writes bad Portuguese.” Even the poems reject the idea of beauty:

Beauty is the name given to something that doesn’t exist,

The name I give to things in exchange for the pleasure they give me.

So why do I say of things: “They’re beautiful?”

To reframe the question: How would you translate a grumpy anti-poet who A, never existed, B, wrote bad Portuguese, and C, was nevertheless a great poet?

Costa and Ferrari make a brave effort, but compared with the sturdy translations of Richard Zenith, who published a book of Pessoa’s selected verse in 1998, these translations can be flimsy and vague. Take two versions of the famous line, “Ha metaphysica bastante em nao pensar em nada.” While Zenith writes, “To not think of anything is metaphysics enough,” Costa and Ferrari say, “There’s metaphysics enough in not thinking about anything,” which hews closer to the Portuguese but limps awkwardly as a line of English verse. Costa and Ferrari’s translations can also contain redundancies. In one poem, a butterfly floats into a room through an “open” window. What other kind of window can admit a butterfly?

There are moments when Costa and Ferrari turn the better line. Where Zenith says, “To think is to have eyes that aren’t well,” which is prosy and slack, Costa and Ferrari say, “Thinking is a sickness of the eyes,” which is cutting and memorable. In a poem about the life of Christ, God is “a stupid dove, / The only ugly dove in the world / Because it was neither of this world nor a dove.” Here, the rude simplicity of these lines matches the bludgeoning tone of the poem. This book is full of remarkable lines and poems that will stay with you for a long time.

Pessoa worked through the din of modernism, but in some ways, he was ahead of his time. To paraphrase Zenith, plenty of postmodernists talk about the experience of utter dissociation, but Pessoa actually lived it. In his work, the only thing nobler than consciousness is the consciousness of consciousness. The self is merely a stage where personalities mingle. His literary cosmos is populated with artificial people who are obsessed with artifice.

It is hard not to see Pessoa’s life as a tragedy of solipsism. It seems like his heteronyms were more real to him than any breathing human being. He had only one romantic relationship, with, aptly, a girl named Ofelia. He sabotaged the romance by writing letters to her under a heteronym — letters that denigrated Fernando Pessoa. He believed that human connection could only be a hindrance to his art because it would take him out of his own head.

In Portuguese, “pessoa” means “person.” The irony of this name is clear. Just as Caeiro tried not to be a poet, Pessoa spent his life trying not to be a person. He preferred seeing himself as a cosmos. What is more human than that?

Forester McClatchey is a poet from Atlanta, Georgia.