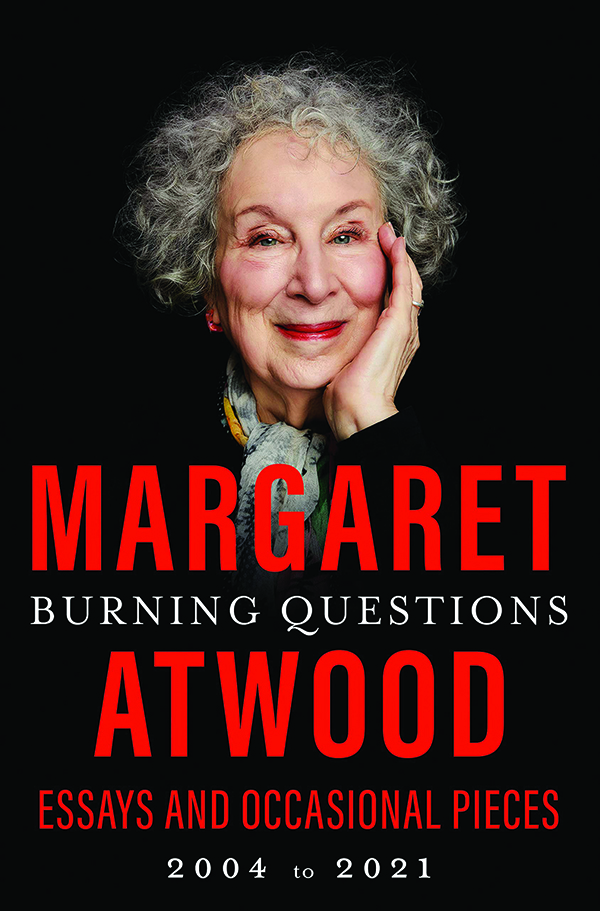

It occurred to me while reading Margaret Atwood’s new essay collection, Burning Questions, that I had almost no idea who Atwood was before reading this book.

Of course, I knew that Margaret Atwood was a writer, and I knew that she wrote the now-inescapable novel/stage play/ballet/opera/Halloween costume/television program The Handmaid’s Tale. I knew, without knowing how I knew, that she was raucously anti-Trump and that between 2016 and 2019, there was a nonzero chance she’d enjoyed several appearances as the feminist talking head on DNC-approved news programs.

I haven’t bothered to fact-check that last bit, but I’m confident it’s true. How could it not be? Perhaps it goes without saying that the Margaret Atwood I thought I was familiar with was the Margaret Atwood of my imagination: What she represented, particularly during the Trump administration, cast a shadow on who she really is.

Atwood, I think, anticipates this flattening of her identity from her readers, though. The new book opens with a meandering and forgettable address at Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication. There is one line, however, that did stand out to me. She says, “I’m an icon. Once you’re an icon, you’re practically dead, and all you have to do is stand very still in parks, turning to bronze as pigeons and others perch on your shoulders and defecate on your head.”

Atwood’s reasoning for including this line was to preempt any nervousness from the people in the audience when this address was originally given. This description of what it’s like to be an icon is accompanied by a long list of other reasons not to be threatened by her: She’s a Scorpio, she’s quite short, and she’s just like everybody else, except, as luck would have it, we know who she is.

Most of the essays in Burning Questions, which range from book reviews to speeches to bits of advice to lamentations about Trump to eulogies for friends, are written in this style. They’re personal and likable: I did not end this book with some special disdain for Atwood, even after 600-odd pages of missives, which is impressive. But they’re also unremarkable. Some of the essays are poorly structured, with their theses hidden from plain view, even after one or two read-throughs. There are others that make no point at all — they simply end. Some are laden with cliches, either in language or in message. Some offer confused anecdotes and analogies for what feels like no reason at all.

None of her writing is awful; just nothing stood out as very good. I couldn’t help but imagine someone my mother’s or grandmother’s age writing some of these pieces and presenting them to a hypothetical writers’ group. Nobody would say, “Quit writing.” But most certainly, everyone would caution, “Don’t get your hopes up.”

The Margaret Atwood that I had dreamed up was perhaps politically at odds with me, even politically naive, but in my mind, she had earned her status as a literary icon. I assumed she’d be someone I disagreed with on some points but would feel enriched by reading her work.

About halfway through the book, I started reaching for explanations for why I was underwhelmed, for why it seemed that this book lacked something.

On page 364, I wrote in the margins: Perhaps Atwood’s status could be chalked up to just how prolific she is?

I could understand why she was a celebrity, but not an icon. Celebrity felt sensible. One hit is usually enough to catapult someone into stardom — especially a hit like Handmaid was and continues to be. She’s had several.

But “star” and “literary icon” are two very different things. J.K. Rowling is a star (or was, until very recently). Atwood is something else entirely. So, the breadth of her oeuvre it must have been.

Atwood has been writing for nearly 50 years and has published 18 books of poetry, 18 books of fiction, 11 books of nonfiction, including essay collections, nine collections of short fiction, eight children’s books, two graphic novels, and several smaller collections of poetry and fiction with independent presses. In the introduction of Burning Questions, she describes a phase where she was publishing something like 20 essays a year, and for a brief period, an even higher number than that.

At some point, you will your way into the zeitgeist if you just refuse to go away. This is true today, in 2022, even in a sea of blogs and digital publications and social media stars. Now imagine that same type of grit in 1961, when she began writing.

But as I continued to read, I started to have doubts about that hypothesis. I started to suspect that really, her status is a byproduct of her political positioning. I started to suspect that few people know who Margaret Atwood is — as a writer or as a person. At some point, the public decided what her significance should be, and it stuck. It wouldn’t have mattered if she wrote 50 books or 14 or three: That’s what “icon” means. It’s a flattening, where some will perch on your shoulders and others will defecate on your head.

As one might be able to guess, in no essay did this shine through quite as much as her reflections on the 30th anniversary of The Handmaid’s Tale, in which she details the ebb and flow of its reception and the political fandom that slowly grew around it. She describes how Americans wondered, “How long have we got?” and projected their private fears about their country onto it and how often people assume she is some kind of prophet. With this type of sustained attachment, this type of politically motivated fandom, it’s no wonder she’s a literary icon. It has nothing to do with her writing at all.

In an essay cheekily titled “The Writer As Political Agent? Really?” she writes, “I don’t believe that writers are political agents. Political footballs, yes; but political agent implies a deliberately chosen act that is primarily political in nature, and this is not how all writers work.”

And Margaret Atwood, it seems, has become just that: a political football.

Katherine Dee is a writer and co-host of the podcast After the Orgy. Find more of her work at defaultfriend.substack.com or on Twitter @default_friend.