There was a time when despots were content to be despots rather than philosopher-kings. The military dictator General Mariano Melgarejo, for example, is supposed to have once explained his title to the office: I’m going to rule in Bolivia as long as I like, and if anyone tries to stop me I’ll have him hanged from the nearest tree. As he was reputed personally to have shot his predecessor, General Belzu, immediately afterwards asking the crowd that had just acclaimed Belzu as a hero whom they were shouting for now, his threat was taken seriously. He was not a man to be trifled with.

Latin American literature would have been much the poorer without despots (at least three Nobel laureates have been inspired by them), but this is not the kind of dictator literature that Daniel Kalder examines in The Infernal Library. Instead, books by rather than about despots are his subject, and by its end one is full of admiration for a man who, over a period of many years and with dogged perseverance, has plowed through whole shelvesful of what must be among the dullest prose ever written. I am no enthusiast for the concept of the banality of evil, but if it has application anywhere, it is here, in books by dictators, especially totalitarian dictators. It is a sobering thought that men who consigned millions to their deaths usually expressed themselves in print with mind-numbing woodenness, waging war on imagination and triumphing in the struggle. Whether they were below average in natural literary ability is a question that cannot be answered without a scientific trial controlled for upbringing, intelligence, level of education, and so forth, but it is clear that they had little regard for the welfare of the reader and it is even possible in some cases that they desired nothing more than to drive him mad with boredom while also compelling him to read and memorize what they had written (or had had written at their behest, for not all dictators actually wrote what appeared under their names). Here, indeed, was something to satisfy the most refined sadist: to torture people with banality piled on cliché piled on falsehood.

For those of us for whom books and reading have been an integral part of existence, perhaps even thinking ourselves superior because of it, it is well to be reminded that literacy and authorship are not in themselves unequivocally good. Kalder points out that if Stalin had remained illiterate, as he might easily have done, the world would have been saved a lot of trouble; nor would the world have been much the poorer without Mein Kampf or Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung. The country churchyard may contain many a mute inglorious Milton, but it might likewise contain many a mute would-have-been Hitler.

The prestige of the book as a cultural artifact has declined steeply of late, as is daily observable almost everywhere, but in the totalitarian century it was undiminished. Every tyrant wanted to publish a book; to have written one (or at least have his name affixed to it as the author) was proof of intellectual gravitas. In the Romania of the Ceausescus, for example, Elena’s great work, a dissertation called Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene, was widely available, even when most other commodities were in short supply. As with Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, this was a book more to be seen with than read; it was the proof of loyal belief in the Ceausescus’ superior intellect (Elena’s husband, Nicolae, was known as the “Danube of Thought”).

According to Kalder, it was Lenin who was the founder of dictator literature, and if he was not yet a dictator when he started writing—it was 20 years, in fact, before he became one—his style was from the first perfectly suited to that of a totalitarian panjandrum for whom debate was treason or worse. To the very slight extent that his prose is readable at all, it is because of the hatred, scorn, and contempt of others that it breathes from first to last. It was as if he had bile, not blood, flowing through his veins. No one who has read Lenin’s prose will find it at all surprising that one of his favorite literary genres once he achieved power was the death warrant.

Yet there was another side to Lenin. Underneath his adamantine exterior there beat a heart of the purest utopian mush. Once the cleansing sea of blood that he spilt had receded, a fairytale world would emerge in which Man would become truly Man (as against what he had been before) and live thenceforth in perfect harmony. How anybody older than 14—let alone someone as intelligent as Lenin—could have believed such a thing is a mystery, but he did believe it.

When it comes to bile among dictator-authors, perhaps only the Albanian Enver Hoxha could equal Lenin and Hitler. Stalin, for whom Hoxha retained the kind of reverence Muslims reserve for Muhammad, was the only person who, in his opinion, never betrayed him: Everyone else he ever knew turned out to be a traitor. As one might expect from a man who is said to have strangled one of his own ministers with his bare hands, there was for him no such thing as honest disagreement—and, actually, there is a plausible warrant for this belief in Marxist epistemology. Hoxha’s prose, like Lenin’s, oozes murder.

However, it would a mistake to think that there is absolutely no variety in dictator literature. Kalder, who occasionally descends to the demotic facetiousness that so many authors now seem to feel it necessary to adopt in order not to appear too elitist, is a good literary critic and makes proper distinctions between his authors. The book would have been a dull one if one dictator’s writing had been as bad as another’s, and bad in precisely the same way, but it was not. The fact that Kalder sometimes finds merit in a dictator’s writing—usually, it must be admitted, before he became dictator, for power corrupts words among the many other things that it corrupts—is testimony to his laudable open-mindedness. His judgments are not facile.

He does not, for example, present Stalin as an intellectual nullity who somehow found himself, as if by pure chance, ruling a sixth of the world’s land surface for a quarter of a century. One of Stalin’s early poems entered anthologies of Georgian poetry before he had reached the kind of prominence in which he could dictate what went into anthologies; he read voraciously and with great care, and had an excellent memory; he was an artful exegete of Lenin’s words to produce any conclusion he wanted, as and when he wanted it; his prose style, which a native Russian speaker told me was the best of all the old Bolsheviks’ (not a high standard, admittedly), had at least the merit of directness and comprehensibility without, of course, elegance, to which it had no pretensions; and he certainly had a high enough opinion of the importance of literature to kill many authors, cunningly sparing others to heighten the tension among the literati. Like many another powerful autodidact, he was coarse and cultivated at the same time; he had a deep insight into the lowest characteristics of human nature, which, with his great intelligence, he used in the service of absolute evil.

Of all the dictators whose writings are examined in this book, by far the most talented—from the literary point of view—was Mussolini. One is reminded of what Valéry said of Napoleon: “What a pity to see a mind as great as Napoleon’s devoted to trivial things such as empires, historic events, the thundering of cannons.” I do not mean to draw an exact comparison, of course, but if Mussolini had not set his heart upon dictatorship he might well have been a significant writer. His First World War diary, for instance, has examples not only of fine writing, but of finer feeling:

This, in its economy, is about as far removed from Fascist bombast as it is possible to imagine. Or again:

It seems, then, that Mussolini squeezed the talent and humanity from himself in his thirst for power. This was something that other dictators did not have to do.

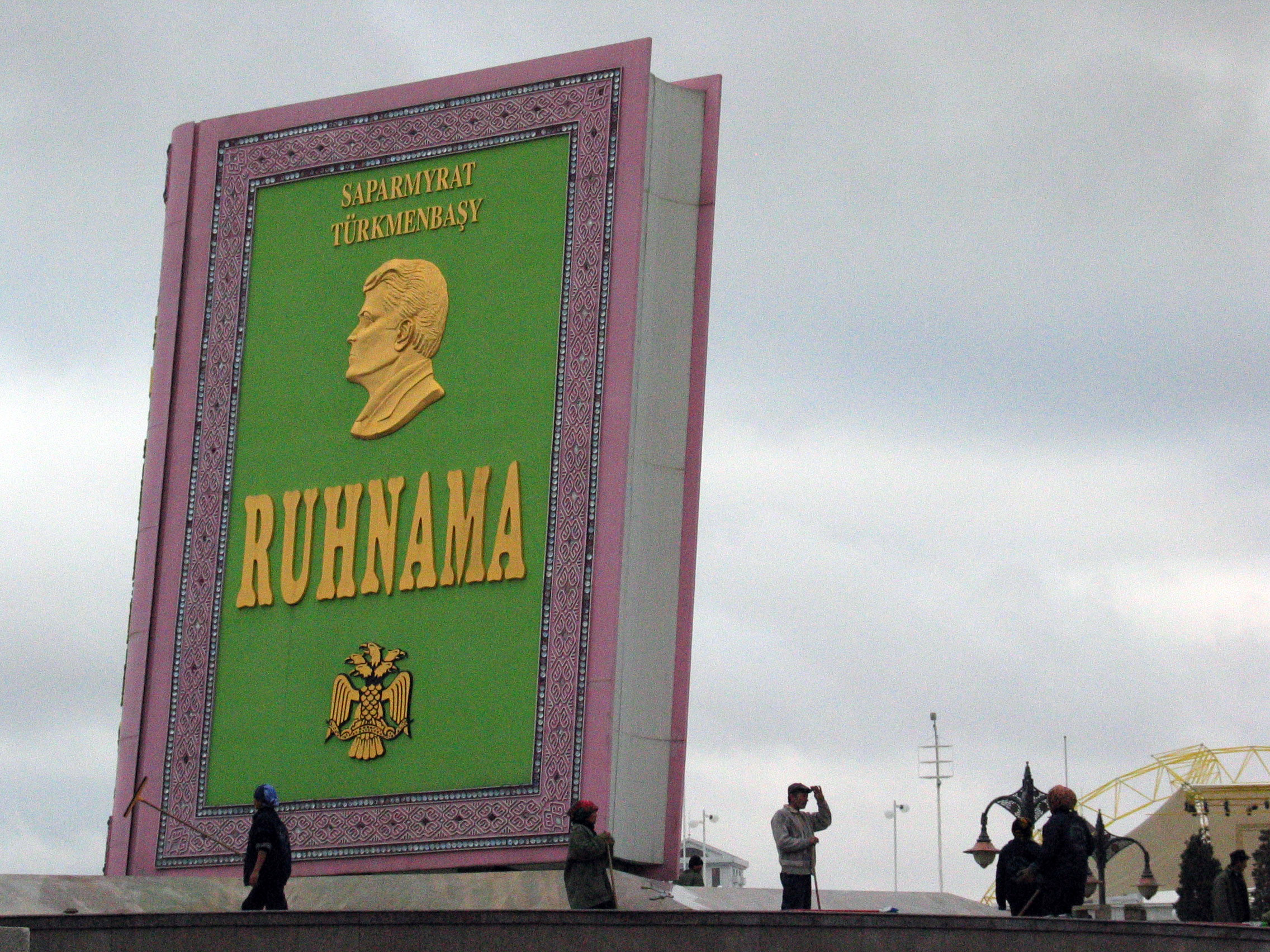

Unlike early Latin American caudillos, the 20th-century tyrant needed a doctrine to justify his power and so he elaborated or distilled one from his mostly mediocre mind. Again, one is full of admiration for an author who has plowed his way through such works as Nasser’s The Philosophy of the Revolution, Qaddafi’s Green Book (which manages to combine brevity with tedium), and the Ruhnama of Saparmurat Niyazov, the bizarre post-Soviet dictator of Turkmenistan, whose vast tome is a mélange of the purest Soviet langue de bois and incomprehensible spiritual verbiage. No doubt these texts are of historical significance, but I am glad that someone else has performed the duty of reading and digesting them for me. The nadir of nadirs is perhaps reached by Kim Jong-il, by comparison with whom his father, Kim Il-sung, was P.G. Wodehouse:

Imagine having this stuff inescapably beamed at you for years on end and having to read, learn, and regurgitate it as if it were the acme of human thought and reflection! North Korea is not so much a country as a vast torture chamber, in which the torture ranges from the acutely murderous to the lifelong.

There are surprises in The Infernal Library. Kalder describes the plotting of Franco’s only novel, Raza, as not wholly incompetent; even more surprisingly, he finds that Franco (in 1942) was not wholly without sympathy for the republican villain of his story. Kalder also finds that Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Government is “well constructed and clear; lucid, even”:

And this is nevertheless quite without sympathy for Khomeini, or any denial of the viciousness of his dictatorship.

The book is not comprehensive, though it is certainly long enough for the average reader. Not included, for example, are the high-minded drivel of Africans Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere and the outpourings of Kwame Nkrumah and Ahmed Sékou Touré. Nor does Kalder point out the one universal characteristic of all the writing that he has examined so dutifully for us: the complete absence of humor.

Has dictator literature a future? If the absence of a sense of humor in public life is anything to go by, it very well might. Indeed, dictator-like literature seems to be increasingly common in academe, as a genre to be imitated rather than eschewed. It is either self-imposed or a manifestation of ideological conformism in the face of social pressure. The author of this most valuable book concludes with Solzhenitsyn’s famous words: “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”