Four years ago, tennis prodigy Frances Tiafoe was profiled in a long and excellent feature in the Washington Post. The article, written by Liz Clarke, laid out Tiafoe’s entire life from birth to teenage years with respect and care and asked an essential question: Could this boy make it as a pro in tennis, one of the most difficult—and unpredictable—sports in the world?

Today, Tiafoe has, for a 20-year-old, done more than anyone could have hoped. After a third-round performance at Wimbledon in July, he is now ranked number 42 in the world; only four Americans rank higher. He also won a round at the Citi Open in Washington, D.C., and two rounds at the Masters event in Toronto, the Canadian Open, including one against Milos Raonic, once a Wimbledon finalist. Tiafoe hopes to do better than he has in the past at the U.S. Open, which begins August 27. He has never won a main-draw match in New York but should have a better chance this year.

For the first time in his career, Tiafoe has a winning season. Once scrawny, he’s now thick in his 6-foot-2 frame and a bigger hitter—on all strokes—than he was before. In his brief career, Tiafoe has earned more than $1.6 million in prize money. That’s not a huge amount in this expensive sport, where coaches, travel, and training can cost a great deal. There are no guarantees, either, like those enjoyed by baseball or basketball players who have signed contracts: In tennis, if you perform poorly or suffer from an injury you make no money. Still, for a 20-year-old, what Tiafoe has accomplished so far is promising. He isn’t bragging about it, but when asked, he’ll tell you that his success is no accident. The young man has worked as hard as anyone in tennis has by his age.

“I told [my family] from when I was about 11 or 12 years old, this is what it’s going to be and you guys just have to sit back and wait for it,” Tiafoe told me in a recent interview. “My dad always believed me. My mom, she wanted me to go to college and then after that you could do what you want. I said, ‘It’s probably not going to go down like that.’ . . . There was always a purpose in what I did on the court because at the end of the day, my parents, they sacrificed for me and my brother. I had to do it for them.”

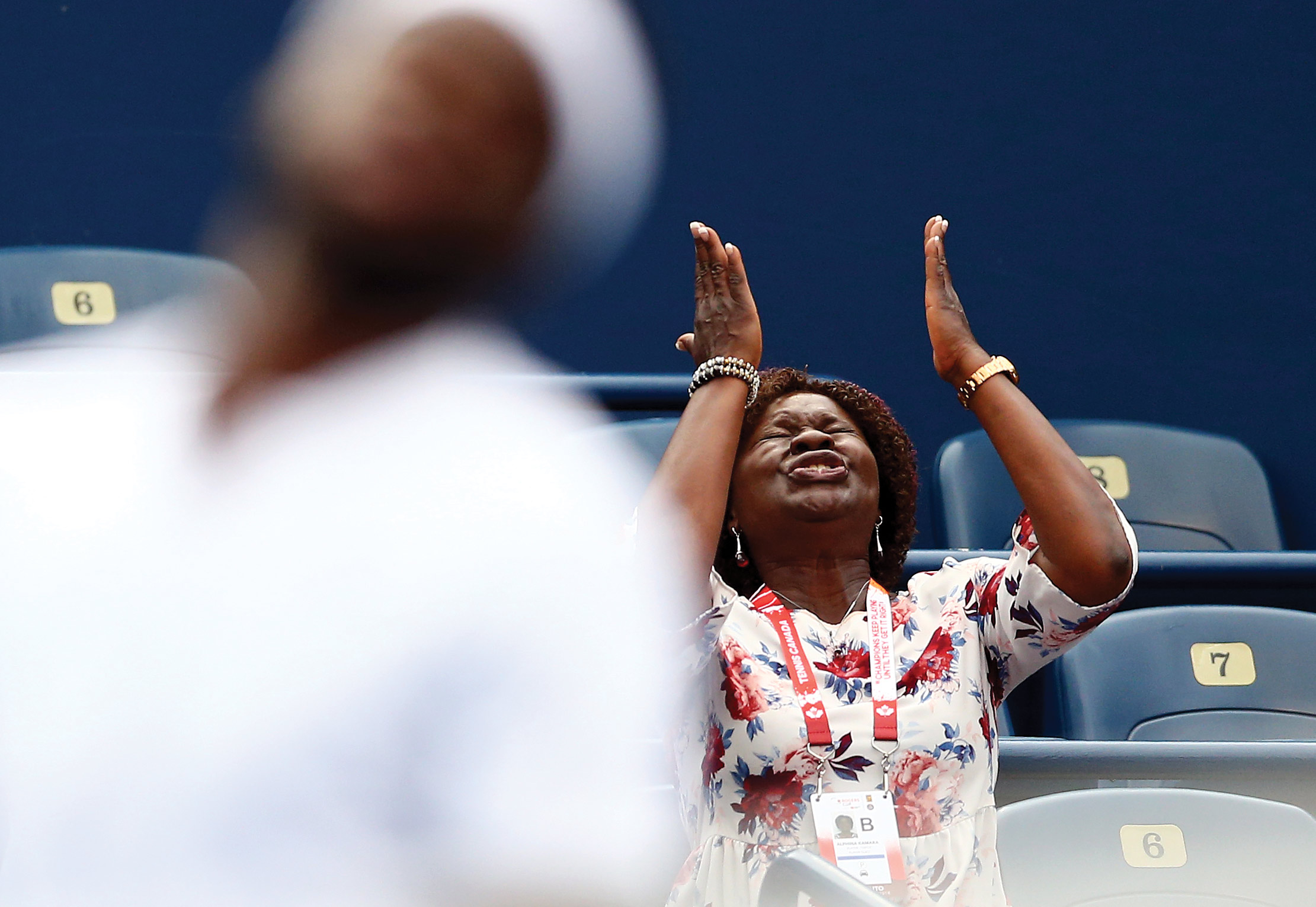

Tiafoe’s parents are from Sierra Leone and met in Maryland. Alphina, his mother, worked as a nurse; his father, Frances Sr., did whatever odd jobs he could find. One was fortunate: helping to build the Junior Tennis Champions Center in a suburb of Washington, D.C. His efforts were so appreciated that Mr. Tiafoe was hired full-time to keep the place in shape. When he worked at night, the young Frances Jr. and his twin brother, Franklin, slept there for the evening.

Both boys played tennis early but only Frances became obsessed. By the time he was 8 he had a full-time coach at the center. By the time he was 15, he became the youngest competitor ever to win the Orange Bowl, a prestigious event for talented juniors. Not long after, he also won the Easter Bowl.

Despite all this, there were worries about Tiafoe’s future. Some observers questioned his style. His forehand had a clear hitch. His serve didn’t have a lot of power and looked stiff rather than smooth. Sure, all that could work among juniors, but not against pros. Weaknesses, even small ones, cost more at the top of tennis, like in baseball for a hitter who can’t react to a 98-mph fastball. And then there were the stakes: An American man hasn’t won a Grand Slam title since Andy Roddick won the U.S. Open in 2003. Could Tiafoe withstand the attention and pressure?

Luckily, Tiafoe seems to thrive under pressure, which is no surprise knowing all his family has been through. As for how he plays, in reality tennis doesn’t work the way many fear. There are rules and popular styles, but also many exceptions. No one would want a student to serve like John McEnroe did, with his legs far apart and his body facing backwards as he tosses the ball and then twists forward. Stefan Edberg had a forehand that looked like it blocked the ball, not hit it. Monica Seles, one of the finest women players in history, hit both her forehand and her backhand with two hands, a technique that few coaches would consider. When Rafael Nadal won his first French Open in 2005, many observers thought he wouldn’t last for long. His forehand, with its speed and an extreme upward motion that looked like no other, seemed to bode shoulder and wrist injuries. He ran more than anyone in matches and practiced with an intensity no one else could sustain. Yet here he is, now 32 and the winner of 17 Grand Slam titles, more than anyone but Roger Federer. Like the two of them, Tiafoe is obsessed with the sport.

“He loves competition,” said Ray Benton, the chief executive of the Junior Tennis Champions Center. “And the most important thing, he’s a good guy with good values. I think the thing that stands out on court is he’s joyful. He’s determined but he’s happy. He has a great smile. He loves being out there. I think he has the potential to go all the way.”

John Isner, now the top-ranked American in men’s tennis, commented on some of Tiafoe’s strengths after a tough win over him two years ago. “He’s got wheels; he’s got the hands; he’s got shots on both sides,” Isner said. “His backhand is world-class. His backhand return is world-class. He was handling my serve better than anyone really, maybe outside of Novak [Djokovic]. I mean, he was really on it. His forehand’s great.”

Yes, Tiafoe has speed and strokes that can be deadly, but his chief strength, surprisingly for a player still relatively young, is his wisdom. His ability to monitor his opponents and then make adjustments to attack them is superb. Tiafoe—who once said, “I like the cat-and-mouse points”—was not just learning to smash the ball when he was a boy but studying the game with care.

“I’m a pretty good problem solver,” he said. “I’m very aware of what’s going on.”

Last year, Tiafoe played Federer in the first round of the U.S. Open, inside Arthur Ashe Stadium with the roof closed. Federer, returning from an aching back earlier in the summer, struggled. Tiafoe went for it and was wonderful to watch. Even though he lost in five sets, the match offered more evidence of his promising future.

“I always dreamed of being on center court, playing the best in the world,” Tiafoe said. “It finally happened so I was ready for it.”

Back in 2008, Grigor Dimitrov, then 17, took a set off Nadal in Rotterdam. With his smooth forehand and one-handed backhand, he made everyone compare him with a young Federer. That year he won the Wimbledon junior championship and the U.S. Open junior event too. Everyone was sure he would be a wonderful pro, and he seemed to progress every year. Last year, Dimitrov reached the highest rank of his career, number 3 in the world. But he has never played in a Grand Slam final as a pro. In all, Dimitrov has won eight career titles. He has made more than $15 million. For Tiafoe, this would be impressive, but he wants more—not just for himself but for his family.

“I still have a long way to go, but I said, ‘Look, I’m going to change everybody’s life,’ ” Tiafoe told me. “ ‘I’m going to buy you all a house, I’m going to do X, Y, Z, and everybody is going to live nice and at the end of my career no one is going to have to worry about anything.’ As far as myself, I want to see myself hold a Grand Slam, be at the top of the game. That’s what everyone wants.”