In 1878, Chester Alan Arthur held one of the most powerful and lucrative patronage positions in the federal government: collector of the Port of New York. Thanks to the percentage system by which he was paid, Arthur took in about $50,000 per year at a time when the president earned half as much. The corruption and political influence of Arthur’s office aroused indignation among good-government reformers, including President Rutherford B. Hayes, who fired Arthur and replaced him with someone devoted to the principles of merit selection for government offices. Arthur’s career looked to have passed its apogee, and his faction of pro-spoils-system Republicans appeared to be in permanent decline.

Three years later, Arthur was president of the United States.

To the extent that Arthur exists in the public mind at all today, it is as one of the most famous owners of the 19th-century muttonchops-and-mustache combination. In The Unexpected President, the first major biography of Arthur since the 1970s, Scott S. Greenberger reintroduces Americans to their 21st chief executive in a solidly researched and fast-paced monograph that reminds us that there was more to Arthur than the sideburns.

A wealthy New York Republican with a reputation for corruption, Arthur never held elected office before his elevation to the vice presidency in 1880. Many mainstream Republicans decried the political maneuverings that placed Arthur on the ticket alongside presidential nominee James A. Garfield, with Senator John Sherman of Ohio calling the nomination “a ridiculous burlesque.” When Arthur unexpectedly assumed the presidency after Garfield’s assassination, there was widespread belief that he would usher in never-before-seen corruption and maladministration.

But it didn’t happen. Although he rose to prominence as a proponent—and a beneficiary—of the spoils system, Arthur came to recognize the wisdom of hiring government workers based on skill, not party loyalty. The change was not immediate; Arthur grew in office, walking away from the cronyism that had advanced his career and championing some of the government reforms he once opposed. By the time he left office, he had done his part to dismantle the spoils system. There are worse ways for an unexpected presidency to end.

Arthur was born in 1829, with the exact circumstances of his birth becoming a matter of controversy during the 1880 election. When he ran for vice president, Democratic operatives accused him of having actually been born in Ireland (his father’s birthplace) and, when that was disproved, in Canada (where his older sister was born). In truth, as those proto-birthers eventually admitted, Arthur was born in the little town of Fairfield, Vermont, the son of an Irish Baptist preacher and his Vermont-born wife. He grew up in upstate New York, receiving a solid, if somewhat scattered, education.

Instead of following his father into religious life, Arthur went into the law and moved from the family home to Manhattan. The growing metropolis comes alive in Greenberger’s telling; the reader gets a sense of how the rural pastor’s son might have felt as he found himself in the midst of aristocrats and immigrants at the heart of American capitalism. Greenberger contrasts Arthur as an idealistic lawyer with the machine politician he would become, detailing the young man’s work on the lawsuit that desegregated New York City streetcars.

In 1856, as abolitionists and slaveholders poured into Kansas, Arthur followed, hoping to shift the balance toward a free-soil state while possibly setting up a new legal practice in the freshly settled region. It is interesting to imagine what would have happened had he remained in “Bleeding Kansas,” where factional violence soon gave America a foretaste of the Civil War. But Arthur had a fiancée, Nell Herndon, and when her father was lost in the wreck of the steamship Central America in 1857, Arthur returned east to comfort her. They married, and he needed to support her in the style to which they both had become accustomed.

The Republican party presented lucrative opportunities. Arthur’s talent for management helped him rise in the party organization and also secured him a state-militia commission with the rank of general during the Civil War, although he was never required to serve in combat.

* *

After the war Arthur found his true calling within the political machine. In those days, customs employees were paid a small salary plus a percentage of the fines imposed on importers who attempted to evade the heavy protective tariffs then in place. Jobs at the New York Custom House were controlled by Arthur’s friend and patron Senator Roscoe Conkling. A flamboyant and abrasive figure, Conkling realized the potential power to be gained by controlling customs jobs in the nation’s busiest port and the money to be raised through “voluntary” contributions from the party men who were lucky enough to get jobs there. That patronage made the GOP powerful in New York, and Conkling was the gatekeeper of it all.

Eventually rising to the position of collector, Arthur was a man to be reckoned with in state politics. He was said to spend as much time on party business as on his nominal job. Greenberger accepts perhaps too unquestioningly the account of Silas Burt, a longtime friend of Arthur who clashed with him over civil-service reform, but Burt’s impression is likely not far from the mark: He considered Arthur’s public persona “bland and accommodating . . . courteous and agreeable . . . genial and ‘cultured,’ ” but saw that in private Arthur was “the leader of a corps of partisan mercenaries.” The Republican party had become, Burt believed, “a mere stalking horse for as corrupt a band of varlets as ever robbed a public treasury.”

The cost of this excess was a backlash against patronage, and reform became one of the leading issues of the day. It divided the Republican party and the nation. In 1878, Hayes, elected as a reformer, fired Arthur and other top members of the Conkling machine and ordered their successors to hire based on merit and not to collect campaign contributions from the workforce.

Two years later, the GOP was divided into pro- and anti-reformers. After a deadlocked convention that year, the party agreed to nominate Garfield, a moderate reformer; Arthur was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket between the two factions. Even though 3 of the previous 11 presidents had died in office, the vice presidency was still not considered an important job and was usually filled by party powerbrokers almost as an afterthought. When Garfield was shot to death in the first year of his term, this lack of consideration looked as though it would come back to haunt the party and the country.

But Arthur was determined to defy the popular impression of him. In part, this may have been due to the shift in public opinion after Garfield’s assassin was discovered to have been a deranged office-seeker who thought Arthur’s elevation would earn him a patronage job. Greenberger suggests that the shift may also have been brought on by Arthur’s rediscovery of the idealism that first brought him into politics. Whatever the cause, the new president spurned his friends from the smoke-filled rooms and tried his best to govern as a reformer. His endorsement of the merit system helped ensure enactment of employment rules still in place today.

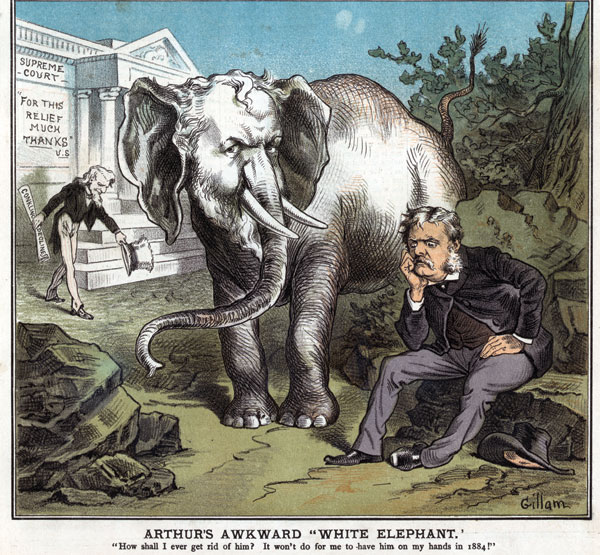

An 1882 cartoon depicting President Arthur contemplating his prospects for reelection in 1884 and wondering what to do about the influential former senator Roscoe Conkling, here represented as a white elephant. [From the March 15, 1882 issue of ‘Puck.’]

Arthur also began the modernization of the Navy, which had acquired almost no new vessels since the Civil War. His administration planted the seeds that would grow into the triumphant fleet of the Spanish-American War. Arthur’s term in office also saw flashes of his erstwhile focus on civil rights and equality, as when he criticized and vetoed a bill that would have shut down immigration from China for 20 years. But after the bill was revised to just a 10-year immigration ban, Arthur signed it. And he pragmatically accepted the defeat of Reconstruction: Although he would have been unlikely to prevail by any other course, in attempting to rebuild the Republican party in the South among dissatisfied white Democrats rather than the black Southerners who were once the party’s natural constituency, Arthur played the part of an establishment politico.

Ultimately, even though Arthur’s accomplishments in the name of reform alienated his old friends, they weren’t sufficient to convince the Republican reformers that the former spoilsman was one of them. Weakened by the demands of office (and by the kidney disease that was already killing him), Arthur made a halfhearted attempt at renomination, then retired to New York. He died in 1886, less than two years after leaving the White House.

Before he died, Arthur burned nearly all of his papers—an act of destruction that makes him a difficult president for biography. Greenberger acknowledges his debt to historian Thomas C. Reeves, whose research for his 1975 Arthur biography, Gentleman Boss, led him to some previously undiscovered papers, including many in the possession of Arthur’s grandson and last living descendant. Arthur is sure to remain fairly unknown, but Greenberger, in revisiting the story of this idealist turned party hack turned reformer, helpfully reminds us of the ways corruption can shape politics and lives—and of how it can be resisted.

Kyle Sammin is a lawyer and writer from Pennsylvania.