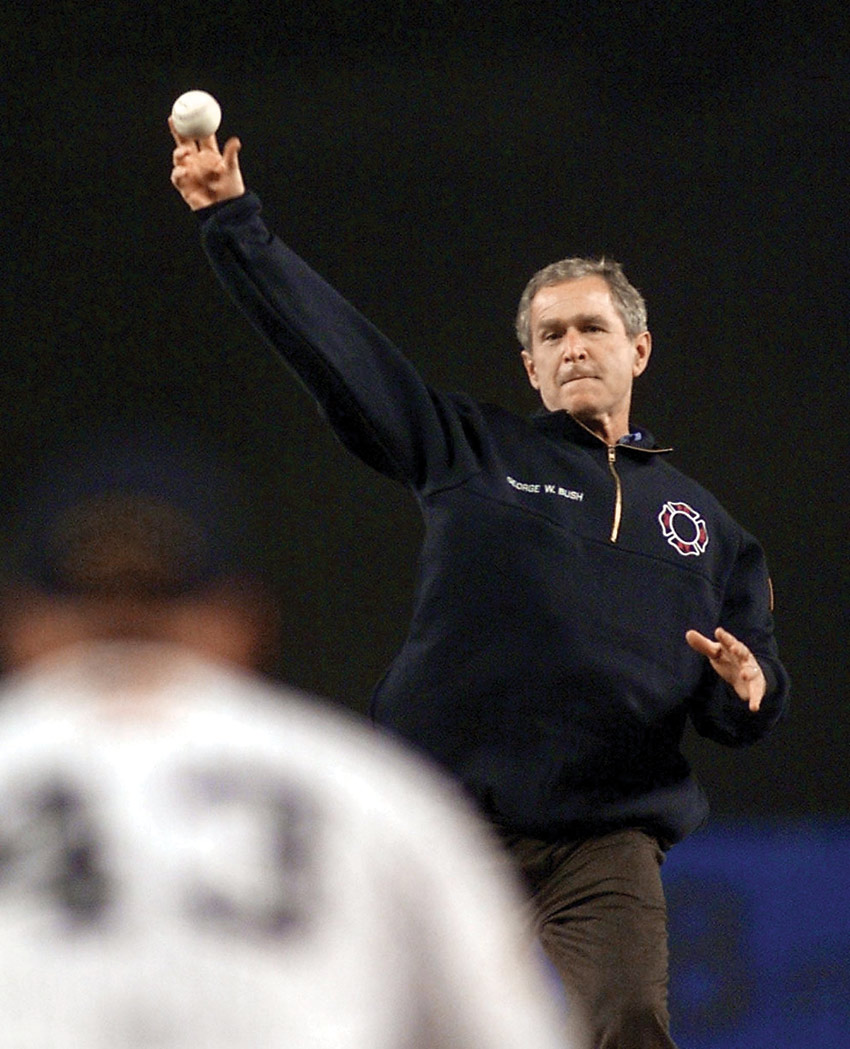

On October 30, 2001, with Americans nursing the national wounds of 9/11, President George W. Bush took the mound in Yankee Stadium to deliver the first pitch in Game 3 of the World Series. Feeling the weight of a nation upon his shoulders—not to mention the weight of a bulletproof vest under his FDNY blue jacket—Bush stood atop the pitcher’s mound, hoisted a thumbs-up, and delivered a perfect strike to catcher Todd Greene. The packed stadium erupted into applause as the president strode back to the dugout.

Reflecting on the moment some years later in a beautifully produced ESPN documentary, Bush admitted, “I didn’t realize how symbolic it was, though, until I made it to the mound.” His national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, saw the moment’s power: “He spoke to the American people in a way that no speech could ever have done.”

No doubt. In that moment America brought together with unprecedented poignancy two of its most deeply rooted and distinctive institutions: the nation’s presidency and its pastime. Bush’s perfect pitch reminded us once again of the deep ties between those two institutions, which extend back to the origins of the republic and the sport themselves.

In his new book, The Presidents and the Pastime: The History of Baseball and the White House, Curt Smith captures this history in great detail, reaching back all the way to George Washington, who was “thought to have played ‘rounders,’ . . . [a] baseball antecedent from Great Britain,” at Valley Forge. “He sometimes throws and catches a ball for hours with his aide-de-camp,” an American soldier apparently wrote. Smith’s account ends with our current president, noting the irony that Donald Trump “truly likes baseball”—before his election, he threw out first pitches, sang “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” at Wrigley Field, and heckled Alex Rodriguez on Twitter, all noble pursuits—yet since becoming president he has unsubtly avoided throwing a first pitch on Opening Day or any other day.

Smith, whose narrative is as affectionate as it is exhaustive, is uniquely well suited to the task of writing this book: Before a journalism career writing books like Mercy! (2012), a centennial history of the Boston Red Sox television and radio broadcasts, he was a speechwriter for President George H.W. Bush, both during and after his presidency; he wrote the senior Bush’s 2004 eulogy for Ronald Reagan, one of the most beautiful speeches of recent memory, and also wrote Bush’s biography.

But Smith evidently intended his latest effort’s subtitle literally: The book is, indeed, a history of baseball and also a history of the White House. Often the two themes intersect. But much of the book is devoted to extended digressions on baseball stories unrelated to the president and vice versa. Wonderful anecdotes about, say, Harry and Bess Truman’s joint love affair with the sport (“Bess’s childhood position was third base,” Smith reports, “baseball’s ‘hot corner,’ perhaps an augury of her husband’s fiery rhetoric”) are hidden among pages of descriptions of Truman’s 1948 reelection bid and his presidential library. In that respect, the book sometimes seems a 22-inning marathon: No matter how many hits and home runs might occur from inning to inning, it’s still a rather long day at the ballpark.

Given the breadth of the history covered in his book, it is no surprise that Smith relies heavily on secondary sources. And while even the best shortstops make their share of errors, Smith boots some easy ground balls—as when he mistakenly says that it was Yankee catcher Jorge Posada instead of Todd Greene who caught George W. Bush’s first pitch in that post-9/11 game. And in his promotional discussions for the book, he has said that the Phillies and the Red Sox “both wanted to sign” Donald Trump for the majors before he started college. This claim is implausible—although it is not difficult to imagine its source.

Still, Smith’s book makes clear baseball’s indelible mark on our national life and the president’s own role in baseball’s annual cycle. This comes through most clearly in his account of FDR—the president who more than any of his predecessors forged a personal bond with the American people, primarily through their radios but also through baseball. Especially on Opening Day: “From 1933 through 1941,” Smith writes, “FDR threw out the first ball every year but one with his unorthodox, overhand lob.” When the nation went to war in 1941, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis asked FDR whether the leagues should keep playing games. In his reply, which Smith reprints in full, FDR urged

The game could bind us together in 2001 precisely as it had—and in part because it had—in 1942.

Football may have overtaken baseball as our national sport, but no job in sports more closely reflects that of the president than a major-league baseball pitcher. Standing atop the mound, alone before the eyes of a stadium (along with, in the World Series, a nation and a world), everything hangs on his next move. Until he acts, we all hang in suspense. And when he finally acts, he sets into motion events to which all others—his foe, his teammates, and even himself—must then react.

By surveying 200 years of history, Smith reminds us that our nation sees and reveres baseball much as it does the presidency. For each, the basic rules were written long ago—and for that very reason, changes in technology or culture do not prevent us from judging current players and presidents against the achievements of their predecessors. “Baseball records reach back into the distant past,” Diana Schaub observed in a 2010 National Affairs essay. “Baseball lengthens memory. . . . It has a constitutional soul that secures the future by preserving the past.” We grade the Dodgers’ Clayton Kershaw by reference to Sandy Koufax, modern presidents by reference to Abraham Lincoln. And by endeavoring to grade the present in the light of the past, we recognize that we ourselves will be judged in similar terms.

“So much does our game tell us, about what we wanted to be, about what we are,” baseball commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti once reflected. “Our character and our culture are reflected in this grand game.”