It would be hard to invent a more pallid or inadequate title than Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer for the exhibition that has just opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Divinity, of course, is always an asset and Michelangelo is a name to conjure with. But neither of the words that follow “divine” does justice to a show that is, in essence, a retrospective of a master who transformed Western painting, sculpture, and architecture beyond recognition. Because most of Michelangelo’s works, by their very nature, cannot travel—being frescoes, architectural sculptures, or buildings—they are represented at the Met through drawings and, where possible, paintings and sculptures. Fortunately, Michelangelo was one of the greatest draftsmen in history, and the Met has now assembled the largest collection of his drawings ever seen, or ever likely to be seen, in one place.

If the Met had done nothing more than bring these drawings together, as was the case with its Leonardo exhibition of 2003, the present show would stand as a landmark, surpassing even the 1988 exhibition of Michelangelo drawings at the National Gallery in Washington. But this new show is much more than that. Sprawled across 10 enormous galleries, it displays some of Michelangelo’s more portable sculptures and panel paintings and even some wooden architectural models assembled under his supervision. Also included is a generous sampling of works by forebears, contemporaries, and followers. The result is a panoptic survey of a career that spanned nearly 70 years. In telling this tale, curator Carmen C. Bambach never oversimplifies. Instead she pays us the supreme compliment of assuming that we are willing to pore over architectural renderings and nearly incoherent squiggles, no less than depictions of the human form, like The Archers and The Fall of Phaeton, that are perfect and complete works of art in their own right.

Only two figures in the history of art, Bernini and Picasso, can rival Michelangelo (1475-1564) in the degree of their influence on their respective ages: Bernini as an architect and sculptor and Picasso as a sculptor and painter. But Michelangelo’s influence was incalculably greater, and not only because it touched all three provinces of visual culture. Conceptually his influence can be divided into two strains, one fortuitous, the other inevitable. If Michelangelo imposed on his generation certain preoccupations with the human form that had always obsessed him, he was also the instrument by which Western painting attained something it had fervently sought for 100 years—the effective depiction of human movement in two dimensions. Perhaps it could have reached that goal without him, but only much later and in a different form.

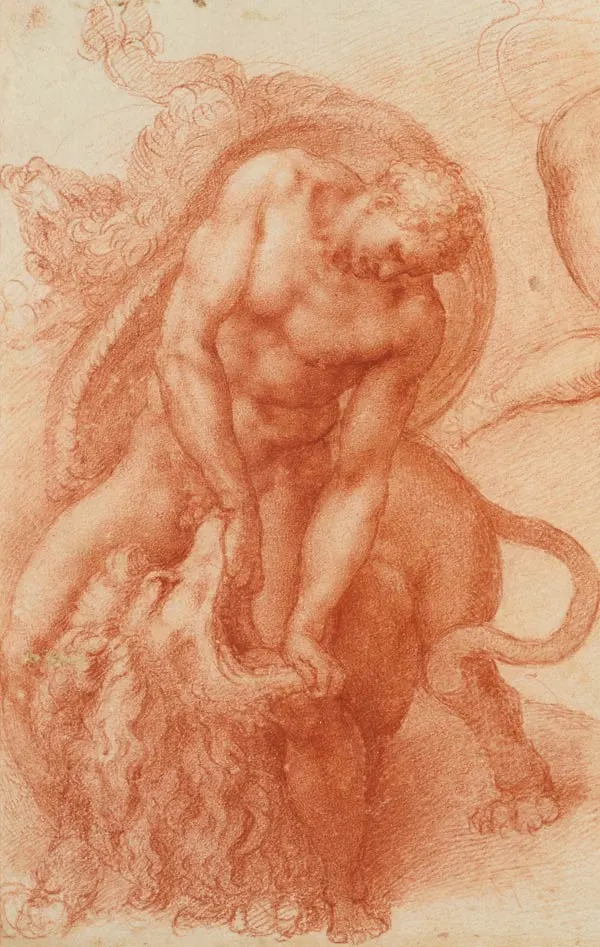

Detail from Michelangelo’s drawing “Three Labors of Hercules” (ca. 1530), showing the young hero killing the Nemean lion. [Credit: Royal Collection Trust / Copyright Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017, www.royalcollection.org.uk]

Born to a banker who had fallen on hard times, Michelangelo Buonarroti began to draw and sculpt at a young age. But he drew in order to sculpt, and to the end of his life he saw himself as a sculptor and nothing else. In fact, he was apt to prove downright testy when anyone, even a prince or pope, tried to divert his energies from marble to painting and architecture. Many of his finest, most finished drawings at the Met were created as models for other painters, like Daniele da Volterra and Marcello Venusti, precisely so that he himself would not have to complete the commissions.

It is ironic then that however great his sculpture was, he had less influence on that medium than on painting and architecture. Even the Pietà in Saint Peter’s and the David in Florence had surprisingly little direct influence on the practice of his contemporaries. As for later works like the rough-hewn Brutus of 1538, which is included in the present show, their influence was even slighter. Perhaps Michelangelo’s sculptures were too eccentric, too much the product of his almost morbid introspection. Especially in his later pieces, he seems to approach quarried stone like some elemental Titan confronting Mother Earth herself. We feel we are witnessing a thrilling encounter to which we should not be privy.

Such was not the case with his paintings. One of the revelations of this exhibition, perhaps inadvertent, is Michelangelo’s singleminded focus on the human form. Nothing else interests him, at least not as a subject for two-dimensional representation. It is unlikely that he drew or painted more than three trees in his entire career. The landscaped backgrounds of the Sistine Chapel ceiling are schematic to the point of evasion, and Michelangelo, a committed neo-Platonist, seems almost unwilling to acknowledge the material world around him—the objects and animals. Rather it is in the human body itself, usually nude, that Michelangelo finds the measure of all that is worth knowing and seeing.

* *

Since the middle of the 15th century, Tuscan artists, among them Pollaiuolo and Botticelli, had tried to depict human movement in two dimensions. But these attempts always failed. Sculptors, however, having access to ancient precedents that painters lacked, had known how to do this for decades. And it was Michelangelo, the sculptor par excellence, who solved the problem by transposing the lessons of sculpture to the art of painting. Only compare his early relief sculpture Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs with the static images of Ghirlandaio and Granacci in the Met exhibition. Then look at the figures on the Sistine ceiling from 20 years later—effectively conveyed at the Met by a large-scale reproduction suspended from the ceiling: Even the seated sibyls and prophets, to say nothing of the torqued nudes and Adam and the Almighty with their outstretched arms, are infused with movement. For the next 300 years, down to the French Revolution and beyond, the forms that were born on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel would continue to populate Western painting. Never again would the stiffness of Botticelli and Piero della Francesca seem tolerable in the work of a living artist of the Old Masters tradition.

Michelangelo made one other contribution to the art of painting that has been almost universally overlooked. For centuries we had been told, by the 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari and others, that Titian and the Venetians were great colorists, but that Michelangelo, in his preoccupation with disegno—the drawn line—had no interest in such things. And yet, with the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel frescoes in the 1980s and 1990s and the Pauline Chapel in the past decade, it should now be obvious to everyone that, in fact, Michelangelo was one of the finest, subtlest, and most original colorists in the history of art. These colors, in their unstable iridescence, reject the deep saturation of the Venetians. And although they too are the eccentric reflex of Michelangelo’s most private preoccupations, such was his influence that they stood at the chromatic core of European painting deep into the 17th century.

Detail from Michelangelo’s design for the tomb of Pope Julius II (1505-1506). [Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1962]

It is likely that most visitors to the Met exhibition will come for the figural drawings and the sculptures rather than for the architectural sheets. But these as well are hallowed, since they enable us to see Michelangelo, as though in real time, working through those formal problems that would result in the Palazzo Farnese, the Biblioteca Laurenziana, and Saint Peter’s Basilica. If you find yourself, anywhere in the world, standing before a classical building constructed after 1550, there is a good chance that it bears some direct or implicit debt to Michelangelo.

Finally, mention should be made of those numerous drawing sheets at the Met that contain, in Michelangelo’s own hand, copies of the poems he composed. It is not widely known outside of Italy that he was one of that country’s most important lyric poets of the 16th century. His sonnets are often difficult going, written as they are in a harsh and lithic Tuscan, but they have a rough beauty and a beguiling honesty to them. As such, they offer an invaluable glimpse into the character of a man who might otherwise remain concealed beneath the visual ravishment of his sundry arts.

James Gardner’s latest book is Buenos Aires: The Biography of a City.