So the Patriots are heading back to the Super Bowl for the 278th consecutive year. The last time New England did not make the Super Bowl, the Hapsburgs were still on thrones. Gosh is it exciting when the same team wins over and over and over!

Maybe the ultimate cause of declining NFL ratings is that audiences are sick of the Patriots, especially since New England is perceived as cheating and as being favored by the officials.

Whether either perception is fair is beside the point when it comes to popularity. The NFL is an entertainment business—game outcomes have no larger significance beyond sports entertainment. If the NFL becomes less popular because the league is perceived as slanted toward New England, then the NFL has only itself to blame. (Roger Goodell’s harsh treatment of the Patriots in the very minor game-ball-PSI scandal makes sense if seen as a league attempt to fight this perception.)

Setting aside the impact of the Flying Elvii’s string of conference wins on public interest in the NFL, the question is whether Tom Brady or Bill Belichick is the root cause. There’s a small chance Robert and Jonathan Kraft are the root cause—the job they do running the Patriots is approximately 10,000 times better than the job Chainsaw Dan Snyder does running the R*dsk*ns, and 1,000 times better than the job Jerry and Stephen Jones do running the Cowboys. There’s a slight but nonzero chance the mysterious Ernie Adams is the root cause. But let’s stick here to coach and quarterback.

The 40-year-old Brady has a legit shot at every major NFL passing record, unless the 39-year-old Drew Brees surpasses him. With a win in two weeks, Brady would pass Charles Haley for most Super Bowl rings by a player: Currently they are tied at five.

Many other Brady stats and accomplishments could be offered. TMQ feels this one may be the single most impressive achievement in football, possibly in all team sports: Brady’s 27 postseason victories is 50 percent better than the number-two quarterback, Joe Montana. Jerry Rice has 44 percent more career receiving yards than the second-best receiver, Terrell Owens, and 47 percent more yards than the best active receiver, Larry Fitzgerald. Rice’s numbers are exceptional compared to the second- and third-best at his position. Brady’s playoff victory total makes him the Jerry Rice of the postseason.

For his part, Belichick’s 28-10 postseason record (he had a win and a loss at Cleveland) places him with 40 percent more postseason victories than the second-best, Tom Landry, and 42 percent more than third-best, Don Shula. Belichick is tied with George Halas and Vince Lombardi for most titles, at five. A win in two weeks would give him first place here as well.

There’s a basic argument that because players perform and coaches stand around watching, a great player, perforce, is superior to a great coach. Here is TMQ’s thought experiment on the question of whether Brady or Belichick is the essence of the New England dynasty. Suppose Tom Brady had been drafted by San Diego and then signed with New Orleans—that is, had Brees’s career—while Brees had been chosen by Belichick at New England and stayed put. TMQ thinks that today Brady would have gaudy passing stats, one Super Bowl ring, and an endorsement deal for Vick’s DayQuil. Brees would have five rings and be getting ready to face the Eagles.

Brady is fabulous but Belichick is the difference. Which pains me to say, since all right-thinking persons should have a love-hate relationship with Belichick. He is the consummate professional at his chosen calling (love) but seems joyless and out of touch with real-world concerns (hate). He gets the best out of players others failed to motivate (love) but has low standards (hate; Belichick’s explanations for the 2007 sideline taping scandal clearly were lies). He draws up game plans that defeat good teams (love) but runs up the score in exhibitions of poor sportsmanship (hate).

Bill Belichick in one sentence: You’d want him coaching your child at football but would not want him teaching your child a class in ethics. Here is your columnist, in the New York Times in 2015, going into detail about how Belichick does what he does.

In other football news, once again no NFL team will appear in the Super Bowl on its home field. The Vikings got closer than anyone else—all other teams that made the postseason in the year a Super Bowl was slated for their home field had honked out by the divisional round.

With Case Keenum sent home, there’s no chance of the first undrafted quarterback since Kurt Warner in 2000 to win the Super Bowl. But Nick Foles can attain an similar first-since distinction: first quarterback since Warner to win the Super Bowl after being signed as a “street” free agent, someone unwanted by all other teams. Brad Johnson won the Super Bowl at City of Tampa in 2003 after being let go by Washington, but wasn’t a street free agent since several teams vied to sign him. Nobody but the Rams wanted Warner, and last winter when the Chiefs showed the door to Foles, only the Eagles showed real interest.

Stats of the Title Round #1. Not only will this be the eighth Super Bowl appearance for Tom Brady and Bill Belichick—it will be the second time the Patriots made the Super Bowl three out of four seasons.

Stats of the Title Round #2. Jacksonville and Minnesota, which entered the title round first- and second-ranked versus the pass with a combined 263 yards per game allowed, combined to allow 644 passing yards.

Stats of the Title Round #3. A combined average of 644 passing yards would have made Jacksonville and Minnesota last- and second-last ranked against the pass.

Stats of the Title Round #4. Teams whose home fields are indoors are on a 0-13 streak in conference title games played outdoors.

Stats of the Title Round #5. Tom Brady is 8-0 versus Jacksonville.

Stats of the Title Round #6. From the point of a 17-0 lead in its first playoff game, Minnesota was outscored 19-62.

Stats of the Title Round #7. The Vikings defense finished first against third-down conversions, allowing just 25 percent, among the best such stats ever. At Philadelphia, the Vikings defense allowed the Eagles to convert 10 of 14 third downs, or 71 percent.

Stats of the Title Round #8. The upcoming season finale will be the 14th Super Bowl in 15 years with Brady, Peyton Manning, or Ben Roethlisberger quarterbacking for the AFC.

Stats of the Title Round #9. Teams with green as their primary jersey color (like Philadelphia) are 6-4 in the Super Bowl. Teams with blue (like New England) are 11-14.

Stats of the Title Round #10. As the home team of record, New England will be asked to choose whether to wear its blue or white jerseys. White jerseys are on a 12-1 stretch in the Super Bowl.

Jacksonville Jaguars running back Leonard Fournette (27) is wrapped up for no gain by the New England Patriots defense late in the fourth quarter against New England. (Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Sweet Defense Series of the Title Round. TMQ contends that in the playoffs, defense trumps offense. When the first- and second-ranked defenses of the Vikings and Jaguars both failed on the same day, this contention would seem disproved.

But winners New England and Philadelphia also field top statistical defenses: Philadelphia finished the regular season fourth against points, New England fifth. In the title round, the Eagles defense held its opponent to one offensive touchdown, while scoring a pick-six—essentially, the Eagles defense shut out Minnesota. The Patriots defense shut Jacksonville out for the final 14:56 of the game, holding the visitors to two first downs in the fourth quarter while forcing a pair of three-and-outs. Both New England and Philadelphia prevailed in the Super Bowl semifinal based on stout defense.

Jax leading 20-10 in the fourth quarter, New England executed a college-style throwback to Danny Amendola, who hit Dion Lewis for a long gain into Jacksonville territory. Lewis fumbled, the Jaguars recovered, and the air went out of the home crowd. Gaining possession on the 33-yard line with a two-score lead and 13:37 remaining, Jacksonville was in position to take command of the AFC’s Super Bowl invitation.

But the New England defense held Leonard Fournette for a short gain up the middle (see more below), then caused an incompletion, then tackled a receiver just shy of the stick.

One could argue—for “one,” read “TMQ”—that Jacksonville head coach Doug Marrone’s decision to launch a punt on 4th-and-1 from near midfield was the killer mistake of this contest, possibly the Single Worst Play of the Season. Gain one yard and New England’s goose is cooked—and if you are afraid to try for one yard, how can you be a champion? New England is the defending champion: You can’t dance with the champ, you have to knock him down! Marrone passed on his chance to knock the champ down, and perhaps you know the rest.

Regardless of whether Jacksonville should have gone for it, the sweet aspect of this sequence from the New England standpoint was that the defense not only forced a quick three-and-out, it made the home faithful forget the fumble, bringing crowd energy back into the game. The sweet bonus was that the incompletion meant the Jacksonville possession took a mere 1:26 off the clock.

Though at the endgame it would be the Jaguars who were pressed for time, when the leading team can’t control the clock in the fourth quarter, the trailing team gets an infusion of hope. Jacksonville leading 20-17, the Jaguars took possession with 5:53 remaining and not only were held to another three-and-out, but two incomplete passes meant a mere 43 seconds went off the clock. Brady got the ball back with 4:58 showing—had Jacksonville simply employed fourth-quarter clock-control tactics, Brady would have had far less time to work with. When Brady got the ball with ample time, you knew the defending champions would win.

Sour Play of the Title Round. The Nesharim leading 14-7 in the second quarter, Minnesota faced 3rd-and-5 on the Philadelphia 16, positioned for a field goal at the least. At the snap, Minnesota has six blockers—the offensive line plus blocking tight end David Morgan—to oppose four rushers. A botched line call leaves Morgan alone on David Barnett, the Eagles’ top pass rusher; Barnett almost immediately hits Case Keenum, who fumbles. The Eagles recover, get a quick touchdown for a 21-7 lead, and never look back. Six blockers can’t even slow down four rushes—that was sour for the Vikings.

Why was the Minnesota line call botched? Earlier, a safety blitz by the Eagles’ Rodney McLeod wasn’t picked up. On this down, McLeod came to the line and faked a walkup blitz, then at the snap, faked a delayed blitz. McLeod never actually blitzed. But the offensive line seemed so concerned with figuring out what he was up to that they forgot to block the blindside defensive end who was always the one most likely to reach the quarterback.

Sweet ‘n’ Sour Title Play. Trailing Jacksonville 20-10, New England faced 3rd-and-18 on its 25-yard line early in the fourth quarter. If the Flying Elvii are forced to punt, their chances of yet another Super Bowl appearance will plummet. On the down before, Tom Brady tried a home-run ball to the deep middle, and Jax had perfect double coverage. Now Brady fakes the same deep action and undrafted, twice-waived Danny Amendola runs a “stick,” sprinting to the first down marker then stopping. (A “curl” pattern.) The first down conversion set in motion the New England comeback—sweet for the home crowd.

On the play, not only is the Jacksonville defense in the soft zone that would prove its undoing, four Jaguars defenders covered no one at all—sour for the visitors. In soft-zone coverage, home-run plays are impossible but often there are one or more defenders covering no one, essentially allowing the offense to play versus a 10-man or 9-man defense. In this crucial play, New England faced a seven-man defense. See more on the Jacksonville soft zone below.

Weasel Coach Watch. Minnesota’s league-leading defense collapsed at Philadelphia. The Vikings finished the regular season first against points at an average of 15.8 points per game allowed—and then allowed 62 points in two postseason games. That number—31 points per game allowed—would have ranked the Vikings last in regular-season defense.

Lest we forget, the Vikings offense was blah too, matching its lowest output of the season. Perhaps the reason was the weasel behavior displayed by Vikings offensive coordinator Pat Shurmur, who in the days before the title tilt was negotiating for his next job, as head coach of the Giants.

If any Minnesota player had been distracted by talking to other teams about a free-agent contract, Vikings management would have been livid. Somehow it was just hunky-dorky for the offensive coordinator to place self over team. The Minnesota offensive coordinator is not focused on the game, and then the Minnesota offense scores only seven points. Surely that’s just some weird coincidence!

Last season before the Super Bowl, Atlanta offensive coordinator Kyle Shanahan was negotiating a new deal for himself with the 49ers, then did a terrible job of playcalling as the Falcons collapsed. Surely that was just some weird coincidence!

TMQ’s Law of Weasel Coaches holds: When you hire a coach who’s only in it for himself, you get a coach who’s only in it for himself. Giants faithful, don’t say you weren’t warned.

Ding dong, the shutdown is over. But the whole thing wasn’t the apocalyptic story it was sold as being. (Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

The Message of the Shutdown Is That Capitol Hill Democrats and Republicans Alike Cannot Perform Even the Most Basic Tasks—and If You Couldn’t Perform Basic Tasks, You’d Be Fired. This is Tuesday, January 23, and presumably the world has not ended, though you never would have expected that from Saturday, January 20, at the outset of the latest government shutdown pantomime. That morning the Washington Post used its largest front-page font—the kind you’d thought would have been reserved for NEW ICE AGE BEGINS or NATIONALISTS OVERRUN CHINA—to declare, GOVERNMENT SHUTS DOWN AS SENATE FAILS TO REACH DEAL.

The shutdown is an important story, but a sense of perspective seemed lacking even more than is common in media and political overreaction. Following the “shutdown,” most of what the U.S. government does remained in operation. Even the Panda Cam was running. Preparations for the shutdown caused government to waste money—agencies had to draw up contingency plans—and if the impasse continued for months, problems would result. But the odds of a months-long impasse were always low. The sense of panic expressed in shutdown reporting was significantly out of phase with all but the worst-case analysis, and worst-case analyses almost never come true.

From the standpoint of television news, senior citizens have become the customer base, and seniors must have worried their Social Security checks would be imperiled (they weren’t), so shutdown stories in dire tones would, presumably, keep older customers watching. From the standpoint of newspapers, bad news about Donald Trump and/or Washington, D.C., has become central to marketing: Depicting the shutdown pantomime as some colossal disaster played to this. People who subscribe to the top newspapers, in print or digital form, just can’t seem to get enough bad news. This means there is economic logic in top newspapers slanting their coverage negative—after all, this is what the customers want.

But the all-negative, all-the-time preferred worldview of the mainstream media leads to a distorted picture of contemporary society. Most things are getting better for most people, throughout the Western nations and in much of the developing world; the reason most things are getting better is that political, social, and technological reforms are more effective than commonly understood; optimism about the effectiveness of reforms is the core argument for the next round of improvements. The all-negative worldview forms a gigantic damping field around this entire line of thought.

I will do my part to counter the prevailing mood with my next book, out in a month. It’s Better Than It Looks argues that the circumstances of the contemporary world are more auspicious than assumed; reports on which reforms made this so; and lays out a practical agenda for addressing climate change, inequality, national debt, and other pressing issues. The book also speculates on why, though in fall of 2016 the United States had never been in better condition, Donald Trump was able to convince 63 million Americans of the reverse.

Minnesota at Philadelphia. Did Case Keenum turn back into a pumpkin on Sunday? He closed the season with 13 victories, nearly double his previous career total, plus as part of a highlight-reel play that will be shown for decades. Yet next season Keenum may have trouble finding an NFL starting job. At last-gasp time the Vikings reached first-and-goal and went incompletion, incompletion, incompletion, incompletion, game over. On third down, Keenum badly missed an open receiver. This sequence alone may cause NFL teams to sour on Keenum.

And did Mike Zimmer turn back into a pumpkin? The Vikes entered the title game 18-7 indoors and 22-18 outdoors under Zimmer—yet the head coach had his charges spend the week practicing indoors on turf, knowing they would play outdoors on grass. Zimmer lined up some excuses why they “had” to practice indoors. Could you imagine Bill Belichick making excuses for taking the easy way out, rather than prepare the team?

The Vikings looked flat from the second quarter on, and often showed little effort. On the third quarter flea-flicker that led to a 41-yard touchdown catch by Torrey Smith, the Eagle wide receiver ran a stop-and-go; Vikings cornerback Trae Waynes came to a stop and just stood there. A long gainer to wide receiver Nelson Agholor happened as Waynes made the high-school mistake of “looking into the backfield” rather than guarding his man; backup corner Terence Newman allowed a 53-yard touchdown catch by looking into the backfield rather than guarding his man. High-school guys look into the backfield because they don’t know any better. When professional defensive backs look into the backfield, it’s because they want an excuse to stand around rather than cover their man. Worst for the Vikings mindset, star safety Harrison Smith was toasted on the 36-yard completion to Zach Ertz that set up a Philadelphia field goal just before intermission.

The Eagles showed the verve Minnesota lacked, playing with emotion. Football is an emotional sport; emotional teams usually prevail. (Of course, home-crowd energy helped, and won’t be a factor in the Super Bowl.) When Patrick Robinson made the interception that became a pick-six, several Eagles hustled like crazy to get into a position to block; corner Ron Darby’s hard but clean block to get Robinson into the end zone was like sticking the fingers of Eagles players into an electric socket. They were zapped with energy for the remainder of the contest.

Going into the game, a question was whether head coach Doug Pederson would let backup Nick Foles run the deep-strike offense the team designed for Carson Wentz, or confine Foles to the dreaded game-manager role. In the first quarter, Foles threw deep and Smith dropped the pass. Pederson did not get discouraged and let Foles continue throwing deep, resulting in completions of 53, 42, 41, and 36 yards. Minnesota looked like it expected a tentative, conservative offensive game plan. Instead it got Foles as if he’d been asked to play Wentz for the scout team. If Pederson keeps the speed governor off Foles in the Super Bowl, it could be a hots-up contest.

The Football Gods Chortled. On Christmas Day, Philadelphia home fans loudly booed the Eagles. Four weeks later they cheered deliriously as the same team made the Super Bowl.

The Football Gods Frowned. Scoring first to take a 7-0 lead at Philadelphia, the Vikings did an elaborate choreographed celebration dance, emulating curling. TMQ likes that the celebration rule was loosened this season, and no team staged more post-touchdown choreography than the Eagles. But in a title game, dancing on the opponent’s field in the first quarter was unseemly, practically daring the football gods to smite thee down. And trust me, you don’t want to be smote.

Jacksonville at New England. The famed aphorism goes, “Fool me once shame on you, fool me twice shame on me.” As TMQ noted that week, during the regular season the Pittsburgh Steelers fooled the Tennessee Titans by using quick-snap tactics to tire the Titans front seven, which coaches do not “roll” to keep fresh. Then at New England, Tennessee was unprepared for the Patriots to use quick-snap tactics to tire the Titans front seven. The first time it was shame on you; the second time, shame on me.

A week later, Jacksonville comes to Foxborough. In recent outings, the Jaguars had built big leads over the Seahawks and Steelers then switched the defense to a backed-off soft zone; in both cases the soft zone handed out passing yards like Halloween candy. So Jax had been fooled once, shame on you. Now in the AFC title game, trailing 14-3, the Patriots took possession at their 15-yard line at the two-minute warning of the first half. No quarterback in NFL annals has ever been better at the two-minute drill than Tom Brady. Yet Jacksonville, till that moment playing stout pass defense using aggressive coverage, shifted to a soft zone. The Patriots flew down the field for a touchdown that made it 14-10 at intermission.

Then leading 20-10 early in the fourth quarter, again Jacksonville shifted to a soft zone—essentially to the infamous “prevent defense,” which only prevents punts. New Orleans should have been in a prevent defense on the final snap at Minnesota in the divisional round, but a prevent defense on the last down is very different from a prevent defense with plenty of time remaining.

New England scored two fourth-quarter touchdowns versus the Jacksonville soft zone. On the day, here were New England’s possession results versus the regular Jaguars defense: field goal, punt, punt, punt, punt, punt. Here were New England’s possession results versus the Jax soft zone: touchdown, fumble, touchdown, punt, touchdown, kneels to end game. By switching to a soft zone, the Jaguars put themselves in the shame-on-me situation.

The other puzzling aspect of Jax’s strategy was running Leonard Fournette up the middle almost exclusively. At Pittsburgh the previous week, Fournette’s big yards came off-tackle and on tosses. In the second half at New England, on first downs—a predictable rushing down for the Jax attack—the Patriots stacked the box with eight defenders and Fournette would plow straight ahead. In the second half Fournette ran outside just once, and gained 14 yards. All other second-half runs were right where the Patriots expected him to run, for little or no gain.

Over on the New England side, for the defense the contest was a microcosm of the team’s regular season: started off shaky, ended up strong. TMQ’s Law of Comebacks Holds: Defense starts comebacks, offense stops them. From the juncture at which Jax took a 20-10 lead till New England took the lead, the Patriots defense allowed just one first down. Then when Jax reached the New England 38 at the endgame, the Patriots defense pushed the visitors backward. Defense started the New England comeback; the slightest glint of Jacksonville offense would have stopped it. But defense prevailed.

For Belichick, the game was a microcosm of years of getting great performances from players other NFL teams didn’t want. Flying Elvii fourth-quarter big plays were made by Stephon Gilmore, James Harrison, Danny Amendola, and Dion Lewis—all let go by other clubs. Gilmore collected a $23-million bonus for signing with New England because his old team, the Bills, thought he wasn’t worth the price; he earned every penny on his spectacular fourth-down defensed pass that put the hosts back into the Super Bowl. Harrison and Amendola both were undrafted, both waived more than once—Harrison was even waived by the Rhein Fire. New England got fine overall performances from undrafted David Andrews and Malcolm Butler, plus a nice catch from undrafted Chris Hogan.

TMQ contends that after practice, Belichick drives around the Boston area and when he sees an athletic-looking young man waves to him and says, “Get in the car, you’re starting Sunday.” It works.

But What Have You Done for Us Lately? The Giants fired Tom Coughlin despite him winning two Super Bowl rings with the G-Persons, and despite Coughlin being the only head coach ever to defeat Bill Belichick in the ultimate contest. It’s been downhill since for Jersey/A, and uphill for Jacksonville, where Coughlin now hangs his hat. Surely that’s just some weird coincidence!

One of the many ways in which the NFL holds up a mirror to American society is blame-shifting—the essence of Washington, D.C., and of NFL coaching firings. The most interesting this season involved Mike Mularkey and Todd Haley.

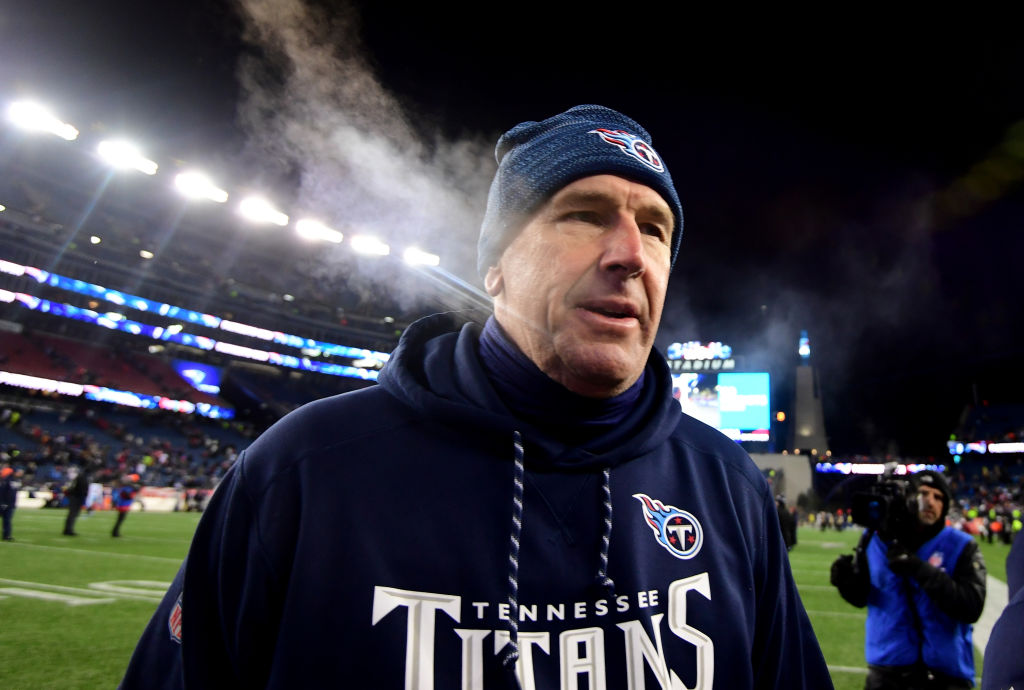

Mike Mularkey walks off the field for the last time as head coach of the Titans. (Photo by Adam Glanzman/Getty Images)

Mularkey guided the Tennessee Titans to their first playoff victory in 15 years, and promptly was cashiered. TMQ thinks a factor was that during the final minute of the first half of the Flaming Thumbtacks’ postseason appearance at New England, not only did Mularkey botch playcalling and clock management, Tony Romo openly ridiculed him on-air for mangling the situation. Network announcers almost always speak of NFL head coaches as little gods: The networks are contractual partners of the league, and the announcers, fundamentally, are house men. When Romo mocked Mularkey on-air, Mularkey’s days were numbered.

The Steelers gave offensive coordinator Todd Haley cab fare to the airport, though Pittsburgh scored 42 points in its home playoff loss, finished eighth overall in points scored in the regular season, and has been top-10 in points scored for four consecutive seasons under Haley. But someone had to be blamed, and head coach Mike Tomlin was not going to put the blame on himself. Quarterback Ben Roethlisberger helped push Haley out the door by complaining to reporters that Haley had forbidden him to audible out of a bad call on 4th-and-1 versus the Jaguars. Roethlisberger knows the NFL pretty well, and surely knew that his remark about the 4th-and-1 call could hasten the departure of the guy he reports to.

Six years ago, when the Steelers lost a playoff game in Denver, Tomlin blamed then-offensive coordinator Bruce Arians and showed him the door; four years ago, after the Steelers lost a playoff game to the Ravens, Tomlin pressured defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau to resign, threatening to humiliate the league’s sole Hall of Fame player-coach by firing him.

Of course, NFL coaches and coordinators are highly paid, and their impressive salaries are partly to compensate them for the inevitability of year-end scapegoating. Still, when the dumbest thing about Washington, D.C.—a low bar—is ritual blame-shifting, it is not heartening to observe the same in the national sport.

Going for It on Fourth and Short Is Not a “Huge Gamble,” It’s Playing the Percentages. Last Tuesday’s TMQ detailed how the Eagles go for it on fourth down, and go for the deuce after touchdowns, more than other NFL teams; this seemed to set the tone for much sports commentary later in the week pointing out the same thing. Tuesday Morning Quarterback has been pounding the drum about going on fourth-and-short being smart football since 2006. This 2007 column reports the results of thousands of computer simulations of fourth-and-short decision making. Note this date preceded by many years the current fad for sports analytics.

Single Worst Play of the Season—So Far. Jax punting on 4th-and-1 near midfield in the fourth quarter at New England was a terrible waffle, but to be fair, many head coaches would have sent the kicker out in this situation. So let’s turn to the second quarter.

Leading 14-3, Jacksonville faced 3rd-and-7 in New England territory just before the two-minute warning; Blake Bortles completed a pass for a first down, placing the visitors in position to initiate a rout. Wait—delay-of-game versus Jacksonville nullifies the first down and causes 3rd-and-12. On the 3rd-and-12 Bortles is sacked.

The delay-of-game penalty that nullified the Jacksonville first down came after a New England time out. That is, Jax had an ample pause to get ready to snap, and instead lost track of the clock. The Jaguars have 23 assistant coaches and members of the “coaching support staff,” yet none of them noticed the play-clock was about to expire. Nor did Bortles, who had two time outs and could have signaled one.

On the sack, Jacksonville was called for holding; New England declined the penalty. That made it fourth down and caused the game clock to resume. Jax head coach Doug Marrone seemed to think the penalty stopped the game clock, but only an accepted penalty stops the clock. Marrone had the punter launch his kick right away, rather than allow the clock to tick down to the two-minute warning, saving Tom Brady precious seconds. The next thing that occurred was the Jax decision to switch to a soft zone, resulting in a quick New England touchdown.

This sequence of events was as fouled-up as the Titans’ performance in the final two minutes of the first half the previous week at New England. Then, just to prove it was no fluke, getting the ball back with 55 seconds remaining in the half and two time outs, Marrone had his charges kneel, as if a four-point lead was all Jacksonville would need to defeat a high-scoring team on its own field. You had best believe that with 55 seconds remaining in the first half and two time outs, there’s no way Bill Belichick would have had the Patriots offense kneel.

Doug Marrone: You are guilty of the Single Worst Plays of the Season. So far.

Next Week. As football hype reaches fever pitch, Tuesday Morning Quarterback reveals this season’s winner of the coveted “longest award in sports”: the Non-Quarterback Non-Running-Back NFL MVP.