Jon Gruden is the new head coach of the Raiders, a high-profile move that may or may not pan out in football terms but is certain to ensure round-the-clock ESPN coverage when the franchise relocates to Las Vegas in 2020. Once at Vegas, the team will be known to this column as the Sinners. If NFL ratings continue to decline, Dave Barry’s joke that the NFL Las Vegas franchise will have topless cheerleaders could become reality.

Tuesday Morning Quarterback aficionados know my compromise with my Baptist upbringing is to be pro-topless but anti-gambling—and it’s a certainty, not a maybe, that the Vegas team will change the league’s relationship with sports betting. Gambling, whether private or public-run, does nothing but harm to society. Yet in its endless quest to enrich ownership regardless of social harm, American sports is throwing its arms around the industry.

Already last fall the NHL became the first American major professional sport to align with the gambling industry, when the puck dropped for the Vegas Golden Knights. (Get the pun?) Bringing the NFL—the nation’s outsize sport—to Las Vegas will formalize betting and athletics as paired interests. This will prove bad for athletics and, more important, harm the families of gambling addicts.

Perhaps the first blame goes to the National Basketball Association, which in 2014 declared a total embrace of betting on pro sports. NBA boss Adam Silver’s argument is that people will wager on sports whether it’s legal or not, so the United States might as well legalize and tax the activity. Silver is a University of Chicago Law School graduate, meaning his grasp of economics is strong; but isn’t “people are going to do it anyway” a situation-ethics argument? (Minors are going to drink even if it’s forbidden, so let’s legalize teen drinking and tax it, and so forth.)

Some states are accepting the might-as-well-legalize-and-tax logic about marijuana. In this case there is a public policy benefit: Legal substitution of marijuana for opioids for long-term pain control would replace a highly addictive substance with something with far fewer side effects. That would be a net plus for society. (Opioids themselves are not bad, but easily abused; a coming TMQ will endorse marijuana for pain control not just for NFL players but for society generally.)

As tax-and-regulate thinking expands from pot to point spreads, money is pursued without the compensating virtue of a social benefit. New Jersey has demanded the ability to legalize and tax sports betting at Atlantic City; currently such wagers are legal only in Nevada. A Supreme Court opinion in the New Jersey case is expected this spring. If the court says yes, several states with long-term fiscal problems caused by political irresponsibility may jump in. The NFL making kissy-face with Las Vegas will provide political cover for a state-led expansion of wagering on sports. One can imagine a future in which state governments pay their unfunded pension liabilities via taxes on sports betting and weed smoking, plus automated speeding tickets.

Silver, the NBA commish, further contends that betting on games increases public interest. By about the halfway point of a pro sports season, many fan bases know there is no chance their favorite team will make the playoffs. Perhaps putting money on the line will keep people interested in otherwise meaningless games.

But by endorsing the bookie business, pro sports opens a door to a place it shouldn’t go. There’s a small concern, that legalized betting will ruin pro sports, and a large concern, that lives will be ruined.

Already the NBA is evolving toward a two-tier league in which a handful of elite teams go all-out to win (the Warriors, Cavs, Spurs, Celtics, Rockets) while other clubs essentially are staging exhibition contests similar to AAU ball. If betting on the NBA’s huge number of inconsequential games becomes legal, the public will assume games are being thrown. Some NBA players with guaranteed contracts, who cannot be waived no matter what they do, will make deals with sports books and throw games here and there—that will be the public perception, at least. If NBA games are fixed, why should anyone care about Bobcats versus Kings or any other inconsequential game?

Because football involves so many players, it’s harder to throw an NFL game than to throw a basketball or ice hockey contest. Once the NFL is in Vegas, though, fans will pay closer attention to the spread. When last-minute events manipulate the spread, fans will believe the fix was in.

Last fall during R*dsk*ns at Chiefs on Monday Night Football, Kansas City hit a field goal with four seconds remaining to take the lead. That meant the Chiefs would win but not cover. On the final play there was a crazy fumble by Washington, returned by Kansas City for a touchdown that had no bearing on the standings but caused the hosts to beat the spread. People who had wagered on Washington, taking the points, were furious: But unless they placed the bet in Nevada they couldn’t complain, since their action was illegal. If Jon Gruden and the Las Vegas Sinners lead the NFL into legal wagering, that will change. When things like the Kansas City-Washington ending occur, millions will believe some bookie paid the R*dsk*ns to make sure the Chiefs covered; or that R*dsk*ns players bet on themselves to lose by more than the spread, knowing they could make that happen.

If there is widespread legal wagering on professional sports, being a coach, now seen as an honorable profession, will become tainted by the hint of sleaze. Public attention focuses on the Kentucky Derby or the Super Bowl; gamblers know the best chance for corruption is in contests the media don’t scrutinize. Last October in the closing minute of the low-interest Bucs versus Giants game, City of Tampa head coach Dirk Koetter could have played for either a field goal or a touchdown. He played for a field goal and the Buccaneers won, but failed to cover; a touchdown would have meant money in the pockets of those who bet on the Bucs. If betting on NFL games becomes legal nationally, moments like the 2017 Bucs-Giants ending will be discussed nationally as evidence of point shaving.

It took the NFL a full generation to recover the prestige lost by the Paul Hornung-Alex Karras football betting scandal of 1963. It will take only one season for the NFL to lose its prestige if another game-fixing scandal occurs. Today’s fans trust that NFL games are honest. Trust is really hard to obtain and really easy to lose.

The betting line and some of the nearly 400 proposition bets for Super Bowl 50 between the Carolina Panthers and the Denver Broncos are displayed at the Race & Sports SuperBook at the Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino on February 2, 2016, in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

As for the larger concern, that legalized betting on sports will ruin people’s lives: It’s bad enough that the $14 billion NFL gets public subsidies in the first place. Should the public subsidize sports organizations that encourage wagering? Already state-run lotteries are the biggest source of institutional harm to average people. Adding the luster of the NFL to wagering would only make this worse.

Forty-four states plus the District of Columbia have government-sanctioned lottos whose purpose is to fleece the poor and working class. There is deep cynicism in state governments claiming to want to help Americans escape poverty, then setting up glittering gambling traps that cause men and women to become mired in cycles of debt. Some lotto players lose everything; the typical state lotto player loses about $120 a year after the token winnings designed to feed gambling addiction. As the Motley Fool notes, “The average lottery player in America loses roughly 40 cents for every $1 in tickets purchased. Talk about a bad return on investment.” Regular state-lotto players are mostly low-income, actively preyed upon by government. That the highly subsidized NFL also preys on the poor by marketing lottos is shameful.

Derek Thompson puts the big picture together, and the key word that applies to the lotto business—sanctioned by government, encouraged by sports owners who boast about their civic responsibility—is shame.

Private casinos darken the picture. Sure, if you go into a casino, have a couple of drinks, play a couple of games, and then get up and leave, that’s a fun evening. Huge numbers of Americans cannot get up and leave, suffering a compulsion that is bolstered when casino managers employ psychology to relieve marks of their savings or their homes. In 2015, Americans spent $36 billion in casinos, transferring $8.9 billion to state governments. How many lives were ruined by this so state governments could have more money to squander?

As professional sports leagues increasingly extol gambling on sports, the Vegas atmosphere—card tables, slots, video poker, sports and horserace betting, lots of alcohol and go-go-dancer style waitresses all under the same roof—may become commonplace.

This could result in long-term decline for the stature of professional football, basketball, and ice hockey—and the leagues will have only themselves to blame. As the NFL moves into Las Vegas, with Jon Gruden the celebrity endorser, enjoy professional sports while you can. They may be determined to destroy themselves via loss of integrity.

The arguments in this column apply to the harmful sort of wagering when people gamble what they cannot afford to lose: the poor who buy scratch-off tickets on payday chasing the illusion of quick wealth, gambling addicts who drain their savings chasing the illusion their luck will change. Of course, a $5 workplace or other friendly bet on the football weekend, or on a March Madness bracket, is harmless. So here’s the only gambling advice TMQ will ever give: Take the home teams in this weekend’s NFL divisional round.

Since the current playoff format was adopted in 1990, home teams in the divisional round are 79-29, a 73 percent victory figure. That’s well north of the 57 percent rate at which home teams won regular-season contests in 2017, or of the roughly 55 percent long-term home-team regular season average.

For the divisional round, the reason the hosts are hosting in the first place is that they are the best teams. Equally important, host clubs have spent a bye week relaxing in hot tubs while their opponents were out clashing.

A week later in the championship round, home-field advantage attenuates. Since 1990, hosts in conference championship games are 35-19, a 65 percent winning figure. For the championship round, nobody’s had the previous week off, and the Super Bowl is just one W away.

But this week, check-mark the home teams for your NFL workplace pool. TMQ predicts the Patriots, Steelers, Vikings, and Eagles will win, based on my incredible insider access to the top-secret information that . . . they are the home teams. And if the visitors win? Remember the Tuesday Morning Quarterback guarantee: All Predictions Wrong or Your Money Back.

Stats of the Week #1. The Panthers finished 0-3 versus the Saints, 11-3 versus all other teams.

Stats of the Week #2. Kareem Hunt and Todd Gurley, who went into wild-card weekend as the NFL’s top two rushers, combined for just 25 total carries in defeats, both playing at home. The less-known tailbacks of their victorious opponents, the Falcons and Titans, combined for 55 carries.

Stats of the Week #3. Adjusting for scrambles, the normally pass-first Falcons coaches called 34 rushing plays, resulting in a 37:35 time-of-possession edge in an old-fashioned clock-control game plan that kept the Rams offense off the field.

Stats of the Week #4. Adjusting for sacks and scrambles, from the juncture at which the Kansas City Chiefs attained a 21-3 lead in the second half at home, needing only to grind the clock, Chiefs coaches called 12 passes and six runs, taking less than 10 minutes off the clock throughout the Tennessee second-half comeback.

Stats of the Week #5. Andy Reid is 11-13 in the postseason; Alex Smith is 2-5.

Stats of the Week #6. The Bills and Jaguars combined for 17 punts and 13 points.

Stats of the Week #7. The Jaguars are 9-0 this year when Blake Bortles does not throw an interception, and 2-6 when he does.

Stats of the Week #8. The Rams, the league’s highest scoring team in 2017, closed out their season with consecutive defeats by finals of 34-13 and 26-13, both below half their season scoring output.

Stats of the Week #9. Cam Newton is 4-4 in the month of January.

Stats of the Week #10. Kansas City became the first NFL club to lose six consecutive home playoff games.

Sweet Play of the Week. Buffalo leading 3-0 in the third quarter, Jacksonville faced 4th-and-goal on the Bills 1 and went for it—fortune favors the bold! Blake Bortles play-faked and threw a touchdown pass to backup tight end Ben Koyack, providing the winning margin in a 10-3 Jax victory.

The catch was sweet, but sweeter is that Jacksonville did not hesitate about the decision, rushing up to the line of scrimmage rather than hemming-and-hawing about whether to send in the placekicker. Sweetest was that Koyack, a little-used player, had only one career touchdown catch going into the contest. TMQ admires the tactic of hitting a no-name guy in a pressure situation.

Sour Kansas City Collapse Plays of the Week. It probably did not help Alex Smith’s confidence that this story appeared on the league’s in-house website a few hours before the Tennessee kickoff. (The lead paragraph is un update added after the game; the original dateline was noon Eastern.) If accurate, the info was leaked by someone in the Chiefs organization who wanted Smith to fail.

Sportsyak has focused on the Marcus Mariota self-pass touchdown and on whether the play should have counted. TMQ was stunned by Kansas City’s playcalling, and how the Flaming Thumbtacks took over the line of scrimmage in the second half.

Kansas City, with the league’s leading running back, was stuffed on a 3rd-and-1 on a drive that could have put the score out of reach: The Tennessee defensive front blew the whole Kansas City offensive line backward. On the next Kansas City possession, rarely used backup Orson Charles dropped a perfectly thrown first down pass on 3rd-and-2—why didn’t Kansas City hand the ball to the league’s leading rusher? Hunt had five carries in the second half, compared to 13 for Derrick Henry. You’ve got the home crowd for energy and the league’s top rusher. Why did Chiefs coaches radio in (adjusting for sacks and scrambles) 40 passes and just 13 rushes?

Chiefs leading 21-10 in the fourth quarter, the Flaming Thumbtacks faced 2nd-and-10. Kansas City came out with a two-man defensive line, the kind of front you’d use against Aaron Rodgers, not Marcus Mariota. The Tennessee offensive line blew the Chiefs’ light front backward as Henry ran nearly untouched for a 35-yard score.

Yes, Travis Kelce went out injured and yes it was the second consecutive playoff contest in which officials signaled a Kansas City score and then took the points off the board. But the Chiefs’ collapse began at the line of scrimmage.

TMQ’s Law of Comebacks Holds: Defense starts comebacks, offense stops them. In the second half, the Tennessee front-seven controlled the line of scrimmage, allowing the defense to start a comeback; the Kansas City offensive line got no push, preventing the home team’s offense from stopping the comeback.

Kansas City’s second-half possession results: punt, missed field goal, punt, turnover on downs. Tennessee’s second half possession results: touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, kneel-down. Tennessee played a fabulous second half; but when the home team has a big second half lead and flames out, especially by abandoning the run, that’s where the attention falls.

It all boiled down to the Chiefs facing 3rd-and-9 in Tennessee territory just before the two-minute warning, needing a field goal to win. Kansas City went empty backfield; Alex Smith was tackled trying to scramble. Then on 4th-and-9 Kansas City again went empty backfield—incompletion. The 3rd-and-9 situation called for “four-down thinking.” Where was the league’s leading rusher?

Sweet ‘n’ Sour City of Angels Plays. The Rams were sentimental favorites for the first NFL postseason contest in Los Angeles in a generation, but played like the 2016 Los Angeles Rams, not the 2017 edition.

Trailing Atlanta 19-10 on the final snap of the third quarter, LA/A had 1st-and-10 on its 20. The Rams came out in a power set with only one wide receiver. Atlanta answered with nine defenders low in the box, the sort of front that is all but impossible to run against; jailbreak, and Todd Gurley loses five yards. Nine in the box meant the lone wide receiver had man coverage and no safety over the top; why didn’t Jared Goff audible to a go route? LA/A recorded a field goal on the possession, but the Rams’ high-scoring offense was, by this juncture, sputtering. Sweet for the visitors.

After the kickoff, Atlanta faced 3rd-and-3 in its own territory. The Rams rushed just three, allowing Matt Ryan ample time to pick out a receiver for the first down conversion. Two snaps later, the Falcons had 2nd-and-long. One could almost see LA/A defensive coordinator Wade Phillips thinking, “This is not going like I planned—I’ve got to bring pressure to shake them up.” Phillips called the rare seven-man “house” blitz. Atlanta countered with a quick hitch to Mohamed Sanu; screen actions are the perfect counter to a house blitz. Sanu motored 52 yards, Atlanta soon got a touchdown at 6 minutes remaining and a 26-13 lead, and the sun began to set on the Rams’ season. (It had already set a few miles away on the Pacific beaches.) Sour for the hosts.

Official Scorer’s Line of the Season. From the Tennessee at Kansas City Game Book:

(6:44) (Shotgun) M. Mariota pass short left to M. Mariota for 6 yards, TOUCHDOWN.

In your fantasy league if you have the quarterback who throws a touchdown pass to himself, shouldn’t you just win the whole league on that play? Mariota also threw a tremendous block on the Derrick Henry run at the two-minute warning that iced the game.

Buck-Buck-Brawckkkkkkk. Low-scoring Buffalo at Jacksonville, the club with the league’s second-best defense against points: There’s no way the Bills will get a touchdown without taking some chances. Instead, in the first quarter, Buffalo punted on 4th-and-inches at midfield. Just to prove it was no fluke, on the next possession, Buffalo punted on 4th-and-2 at midfield.

Now it’s late in the second quarter, game scoreless, the visitors have 1st-and-goal on the hosts’ 1. The Bills have a top-ranked running game, and on the day would rush for 130 yards. It’s hard to believe that with the Bills needing only one yard, any defense including the 1985 Bears could have stopped four consecutive rushes by LeSean McCoy. Instead, on 1st-and-goal Buffalo coaches call a fade-lob pass, something the Bills have not done well all season. Offensive pass interference on Kelvin Benjamin, and the possession ends with a field goal. Buffalo never gets into the Jacksonville red zone again.

The low-voltage Bills scored a total of three points in the fourth quarters of their final seven games combined. Entering the playoff contest knowing that, to that juncture, the Bills had not posted a touchdown in the fourth quarter for six consecutive games—that is, knowing points would be very hard to come by—head coach Sean McDermott should have been willing to take a few chances. Instead he made ultra-conservative calls at every big moment in the game, resulting in a grand total of one field goal.

To Each His Dulcinea, That He Alone Can Name. Catching a pass with his Rams down 26-13 late in the fourth quarter, Sammy Watkins of LA/A celebrated wildly, as if the Rams had just won the game.

How Can I Arrange to Get Trump to Denounce My Upcoming Book? Henry Holt, publisher of the new Michael Wolff book that seems right in its central contention (Donald Trump is unfit for office and the people in his inner circle know it) while flimsy in specifics, must have been over the moon when Trump’s lawyer waved the preposterous cease-and-desist letter. Money cannot buy that kind of publicity. Plus, your columnist loves the legalese “cease and desist.” Holt’s lawyers should have countered, “We’re willing to cease but we refuse to desist. Alternatively, we’ll desist but not cease.”

Wolff’s book fits into a publishing category that was made respectable by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—placing into quotation marks material that is not quotation, in the meaning of, “This is what was said.” The Woodstein books, then the Bob Woodward volumes that followed, were excellent reporting and rich with insight as regards the gist. But they veered into sham by inventing dialogue placed within open-quote and close-quote. Woodstein and then Woodward pretended they knew word-for-word what various White House insiders said in private when no recorder was running, no one was taking notes, and no witnesses were present. Since Woodstein, too many writing on the White House feel they must contrive dialogue. Now Wolff joins this procession.

Perhaps you are thinking it’s old-fashioned or literalist to believe that in nonfiction, and quotation marks should be employed solely to mean, “This is what was said,” rather than the current meaning of, “This is how Netflix could stage the scene.” Christopher Lasch wrote in 1979 that in contemporary American culture, “The important consideration is not whether information is true but whether information sounds true.” For a generation, sounds true has been nudging out true in newspapers, politics, television, and, worst, books.

In Cold Blood, published 1966, set the precedent for applying the adjective “nonfiction” to material with a hefty dose of invention, and with quotation marks placed around passages that could not possibly be actual quotations. A decade later, when the Woodstein books proved right about their gist, and important to the public, publishers and booksellers made the error of sanctioning invented dialogue not in theater or fiction, where invented dialogue is admirable, but in nonfiction, where this technique has no place. It’s been downhill since.

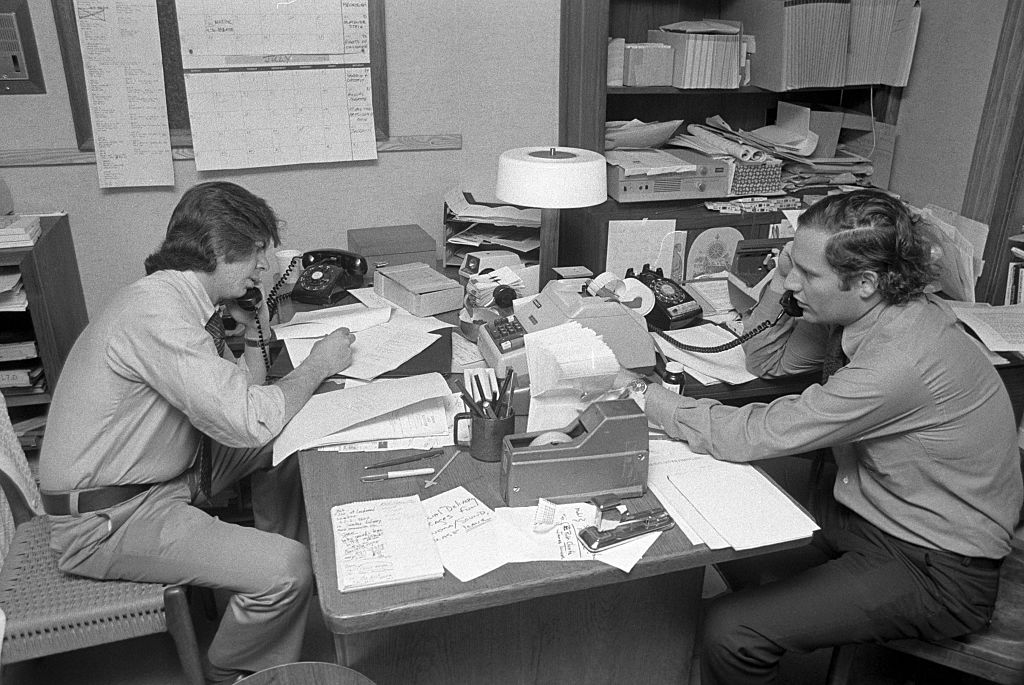

American journalists Carl Bernstein (L) and Bob Woodward (R) making phone calls before a radio show taping on June 17, 1974, in New York City. (Photo by Waring Abbott/Getty Images)

The publishing reality is that books sold as full of shocking insider anecdotes and astonishing quotes are more likely to gain attention than books sold as well-reported, well-researched analysis. Had, for example, Bob Woodward’s book about the early Clinton presidency, The Agenda, contained material saying words to the effect of, “I have good reason to believe that what was going on was X,” the book would have been faithful to factual standards but likely not done as well at grabbing attention as it did with scenes of private presidential dialogue placed into quotation marks as if Woodward had been present. This conflated speculation with fact, helping bring about what Stephen Colbert memorably called the era of truthiness.

Fake-news accusations against the establishment media have for several decades been abetted by the publication of “nonfiction” books that may reflect genuine research but are built around unverified claims or eye-catching quotations that cannot be accurate, in the only sense that should matter to nonfiction quotation marks: “This is what was said.” By placing into quotation marks extensive material that is not quotation, publishers debase the written word. Then political phonies like Trump realize that a culture in which truth has been debased is one ripe for demagoguery.

Now we have Michael Wolff. First, Fire and Fury grabs headlines by claiming shocking, astonishing inside-the-White-House statements placed within quotation marks. Then after achieving the publicity splash, Wolff allows that it’s not like he’s saying his own splashy claims are proven. Isn’t this the same basic sequence as Trump repeatedly changing his contentions based on whatever’s best for publicity on that particular day?

Wolff’s depiction of a White House with an overgrown baby in command is important on the gist. But how can anyone believe verbatim quotations of conversations when he wasn’t present and no one was taking notes? (Barton Swaim goes into more detail on Wolff’s postulations.) By allowing sounds true to rule the day, publishers make bookstore aisles more entertaining, but the craft of writing less professional and the contentions of intellectuals less credible—which plays into the hands of the demagogue.

Failed Fourth Down Try Helps Saints. New Orleans recorded its first touchdown versus Carolina on 2nd-and-10 from its 20. The Cats ran a safety blitz, which tells the quarterback he faces Cover 1: a single high safety. Speed merchant Ted Ginn, on his fifth NFL team, ran a deep post and was covered only by Luke Kuechly, the Carolina middle linebacker. In the Tampa Two philosophy the Panthers’ defense employs, the middle linebacker does backpedal deep on some actions—but the middle linebacker covering the opponent’s speed merchant was a serious coverage breakdown. Ginn went 80 yards for a touchdown.

The Saints’ final, and game-winning, touchdown was set up by a 46-yard catch-and-run on a short crosser to Michael Thomas, the Saints’ best receiver. On this down Thomas was covered by: Luke Kuechly, the middle linebacker.

The endgame supported TMQ’s contention that it can be better to go for it on 4th-and-short and fail than to boom a punt. Leading 31-26, New Orleans faced 4th-and-1 at the midfield stripe at the two-minute warning. New Orleans lined up as if to go for a game-icing first down. Expecting a run, Carolina put all 11 men on the line of scrimmage: the rarely seen Cover Zero, no safety anywhere. Yours truly shouted, “Throw deep! Throw deep!” The plan, though, was to try to draw the Panthers offside. When this did not eventuate, as Howard Cosell would say, the Saints called time.

Most in the stadium must have assumed that after the time out, the Saints would punt. Instead, Drew Brees and the offense trotted back in. TMQ thought they’d simply rinse and repeat: again try to draw the Panthers off, and if they failed, take the delay-of-game penalty. Instead it’s a snap! New Orleans ran a confused, shaggy looking attempt at a deep pass, intercepted by Carolina. Perhaps during the time out, Brees and the New Orleans coaches realized he should have audibled to a deep pass versus the Cover Zero, expected to see that defense again, then tried to throw deep versus the regular defense the Cats sent out.

The interception was made at the Cats’ 31 by safety Mike Adams. Because it was fourth down, Adams should have knocked the ball down.

Coaches teach, “Fourth down, knock it down.” Had the pass simply fallen incomplete, Carolina would have taken possession at its 47—the fourth-down line of scrimmage—rather than at its 31. Since an incompletion would have been better for Carolina than the interception, Cats captain Luke Kuechly tried to convince the side judge that Adams bobbled the ball: “Please sir, we dropped it, you can’t believe how terrible we are!” But why did the veteran Adams not just knock it down? Because he knows, as every NFL defensive back knows, that each pick adds $1 million to his next bonus.

Carolina nearly reached the New Orleans red zone before the Saints’ front four asserted itself and sealed the win. As noted by reader Mike Baker of Sunbury, Ohio, the Fox booth crew criticized Sean Payton for not doing the expected and sending in the punter. TMQ contends that NFL coaches don’t go for it on 4th-and-short because if they attempt fails, the coach will be blamed, while if the coach orders a punt and his team loses, the players get blamed.

Fortune Favors the Bold! Leading 13-10 on the first possession of the third quarter at LA/A, Atlanta reached 4th-and-1 on the Rams 21. Rather than launch a field goal, the Falcons rushed up to the line of scrimmage for the “Brady sneak”: a 4th-and-1 quick-snap on which the quarterback simply dives straight ahead. The Rams seemed surprised. Atlanta converted the first down, and though the Falcons ultimately settled for three on the drive, the 16-snap, 8:15 possession drained a lot of clock and put the hosts into jittery-nerves mode.

On Broadway They Save the Best for Last. For the second consecutive year, Potomac Drainage Basin Indigenous Persons quarterback Kirk Cousins goes into the offseason hoping for a long-term contract—and for the second consecutive year, goes into the offseason after an awful performance. In the season finale of 2016, and again in 2017, the favored R*dsk*ns sputtered on offense and lost. Cousins threw one touchdown pass and five interceptions in those contests.

The reason the show-biz rule is “save the best for last” is that people remember whatever happens last. As Cousins’s agent scours the league asking for mega-money, general managers will remember two games: the whiff to Jersey/A that ended 2016 and the whiff to Jersey/A that ended 2017. Between another season-ending whiff, and Jimmy Garoppolo firmly entrenched at the 49ers, the market for Cousins may undergo a correction.

Adventures in Officiating. Late in the first half at Los Angeles, the Rams completed a short pass and rushed up to the line to spike the ball with five seconds remaining, out of time outs. After a lengthy disputation, officials ruled the catch an incompletion, then put the clock back to 14 seconds. That is, LA/A benefitted from having its catch overturned.

As Michael David Smith noted, the officiating crew for the Flaming Thumbtacks at Chiefs contest did a horrible job. Marcus Mariota was stripped of the ball just before the field goal that would become Tennessee’s first points. Referee Jeff Triplette blew the play dead as Mariota fumbled, disallowing Kansas City’s recovery. Triplette said Mariota’s forward progress had stopped because he fumbled. But any player’s forward progress stops at the instant of a fumble. Triplette’s interpretation would result in there never being fumbles in football: Every time the ball popped out, the play would end.

When Tennessee scored to take a 22-21 late lead, Mariota was sacked and fumbled on the deuce try. Kansas City returned the ball for a defensive deuce that appeared to put the home team ahead 23-22, but again Triplette ruled no fumble because of forward progress. In this case Mariota was driven backward before losing the ball, the kind of action that zebras usually do call forward progress. But twice Kansas City got a takeaway in a key situation and twice Triplette awarded possession back to Tennessee.

Later, when Mariota caught his own tipped pass for a touchdown, Triplette announced to the crowd that Mariota had been an eligible receiver on the play because he did not line up under center. That’s the rule if the play is a designed pass back to the quarterback. Once a defender tips a pass, all offensive players become eligible. Triplette was talking about something irrelevant to what happened on the play.

For years, Triplette has been the NFL’s worst white-hat guy. What was he doing officiating a playoff game? That he retired immediately after mismanaging a playoff game hardly fills one with confidence about NFL integrity. As the NFL moves into the Las Vegas world, what will happen the first time there is botched officiating that influences the point spread?

Next Week. If the home teams don’t win in the divisional round, I will dream up some phony rationalization to make it seem like I knew it all along.