If 19th-century Comstock Lode mining baron John Mackay is remembered at all today, it is as the grandfather of the wife of Great American Songbook composer Irving Berlin. Based on The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West, that is Mackay’s rightful place.

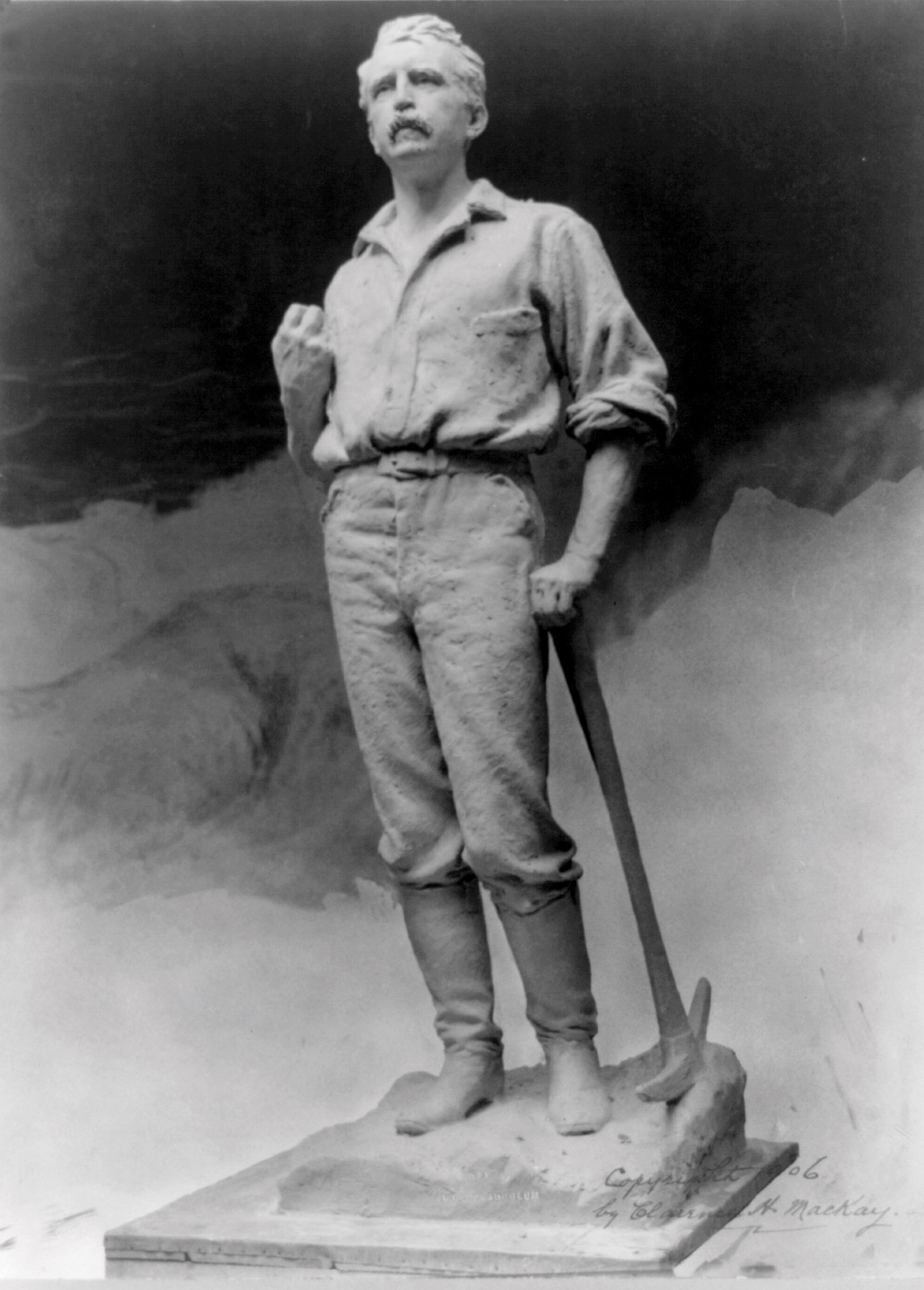

Presumably, author Gregory Crouch intended to deliver a sweeping study of an industry through the lens of biography, like Ron Chernow did in Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Unfortunately, Mackay, the nominal subject, is colorless. He was honest in business, well-liked by employees and children, and an autodidact who for years lived modestly above a company office, reading schoolbooks after long days supervising his mines. Mackay was a technological and logistical innovator, and he might have, like the Guggenheims, built an international mining empire—but Mackay instead spent almost the entirety of his active career working the huge Comstock Lode in Nevada.

Crouch vividly describes the perils of deep-shaft mining, such as decapitation from leaning out of the shaft elevator. He offers a thrilling tale of Mackay’s fight against a fire that almost destroyed the mine; this is one of the few places in the book where Mackay’s personality shines through. But there are long passages of filler (tailings, in the mining idiom) on Mackay’s birth country of Ireland and New York City—neither important places for his adult life—and even an unnecessary discussion of seamstresses in the millinery trade.

The discovery in the late 1850s and subsequent mining of the Comstock Lode was a major economic event. As Crouch demonstrates, like other Second Industrial Revolution industries, mining required huge capital investments: Timber stands, water supply, pumping equipment, railroads, and massive numbers of horses were needed to extract the silver, refine it, and transport it to San Francisco for distribution to other markets. The scale and remote location created chokepoints and pressure for vertical integration. Crouch turns this into a good-versus-evil battle between Mackay’s group (known as the Bonanza Kings) and another led by the unsavory William Sharon. Yet Mackay had unsavory partners too, and the two competing groups struck deals when they needed to.

Even more than the 1849 Gold Rush, Comstock silver production transformed the San Francisco financial markets and spurred California’s development. The flood of silver destabilized the Tokugawa shogunate, launched a quarter-century of silver-coinage politics in the United States, and ultimately led to the gold standard in Germany. But Crouch provides little context for these developments. Nor does he do much to compare the Comstock Lode with earlier massive silver finds, like the 16th-century discovery of silver in Potosí, Bolivia.

As a business history, the story sprawls too much and might have been have been better framed around the mining industry’s transformation of the West. Crouch’s discussions of mineral rights and stock-market raids are impenetrable, even for a transactional lawyer like me. Nor is there a clear treatment of the cost of production or the rate of worker injuries. The book lacks a technical glossary and adequate diagrams; to find the bibliography and endnotes, the reader will have to visit the author’s website.

After the Comstock Lode played out, Mackay’s late-in-life investment in the company that became International Telephone and Telegraph makes an equally unsatisfying good-versus-evil tale. Mackay’s group laid vast amounts of international cable and undercut the monopoly telegraph prices of Jay Gould’s Western Union, but the economics of communication networks led to overcapacity and a modus vivendi similar to that of the railroad pools.

Later chapters focus on Mackay’s wife Louise. When they met, she was an impoverished, widowed seamstress raising a daughter. Aspiring to finer things, she left for Paris to become a standard-issue Gilded Age society lady who lived mostly apart from Mackay. She rubbed shoulders with the upper crust, entertained lavishly, and married off her daughter to a wastrel aristocrat. Perhaps Ellen Mackay Berlin appreciated her grandmother as a prototype for Irving Berlin’s “Hostess with the Mostes’ on the Ball.”