In Umberto Eco’s medieval whodunit The Name of the Rose, the narrator, a Benedictine novice, comes to realize that “books speak of books: it is as if they spoke among themselves.” Armed with this newfound awareness, he sees the monastery library in another light—not as a quiet, cloistered retreat but a more animated realm, “the place of a long, centuries-old murmuring, an imperceptible dialogue between one parchment and another, a living thing.”

Christopher de Hamel, one of the foremost authorities on medieval manuscripts, is attuned to such murmurings. In his deeply edifying and hugely entertaining new book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, he states that ancient, unrecorded books begin as “silent and inanimate objects” but after they have been examined, identified, and catalogued, they come alive and develop unique personalities. De Hamel was originally going to call the book “Interviews with Manuscripts,” for “books can talk” and they have plenty to reveal. “Sit back,” he instructs his reader at the outset, “turn the pages and listen quietly to what the books tell us. Let them talk.”

English-born de Hamel has been listening to books and sharing their secrets throughout an illustrious bibliophilic career, first as the head of manuscripts at Sotheby’s and then as a fellow and librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. At the college’s historic Parker Library, he was curator of hundreds of rare and priceless medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. His published works include a history of the Bible and a number of books on illuminated manuscripts. To call de Hamel a passionate paleographer would be to sell him short.

In his new book, de Hamel scrutinizes a dozen illuminated manuscripts, ranging from the 6th to the 16th centuries. They encompass the Gospels, astronomy, music, literature, and Renaissance politics, and they take de Hamel to some of the greatest libraries in the Western world, from Oxford to Paris, Munich to New York, St. Petersburg to Los Angeles. We travel with him and gain exclusive access to books that, despite being cornerstones of our culture, are so fragile and precious they remain off limits to the general public. As de Hamel pithily explains, “It is easier to meet the Pope or the President of the United States than it is to touch the Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry.”

A portrait of Saint Luke in the 6th-century Gospels of Saint Augustine. [Penguin Press, courtesy of Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge]

Working chronologically, de Hamel begins his journey with the Gospels of Saint Augustine, created in the late 6th century and housed today at the Parker Library. Considered the oldest non-archaeological artifact to have survived in England, the book was reputedly entrusted by Pope Gregory the Great to Augustine on his mission to convert the heathen English to Christianity in A.D. 597. It was a practical book, carried in processions and during the liturgy, and as such would not have been venerable enough to have become a relic. How far it has come: Today it is viewed by many as “a religious relic of the highest spiritual value.” De Hamel records an instance in 2005 of a visitor weeping and kissing the ground in front of its glass display case.

From here de Hamel trawls the centuries, singling out for each chapter one text he deems emblematic of the era. In Dublin he shows us the Book of Kells, another manuscript of the four Gospels and the iconic symbol of Irish culture. “It is probably the most famous and perhaps the most emotively charged medieval book of any kind,” de Hamel writes. Over half a million people buy tickets and stand in line to see it every year. Its script or decoration adorns souvenirs and pub walls, banknotes and postage stamps. James Joyce traveled with it, studied it, and imitated it.

De Hamel’s tour also takes in a Spanish monk’s collection of grisly interpretations of the apocalypse, an anthology of satirical poems, tender love lyrics and rowdy drinking songs, and a treatise for princes on warfare (which includes the dastardly stratagem of lobbing glass bottles filled with venomous snakes onto the deck of an enemy ship). At times his investigations lead him off on intriguing detours—as when an examination of the Leiden Aratea, a Carolingian picture book of the constellations, triggers a discussion about the then-non-taboo practice of copying. In another instance, a study of an Old Testament commentary by Saint Jerome, the translator of the Vulgate Bible, branches out into a lesson on the act, and the art, of writing.

* *

Two chapters are particularly stimulating. We learn that the Hours of Jeanne de Navarre was a private and personalized prayer-book created for a French king’s daughter. After its owner was struck down by the Black Death in 1349, it began a new life on an eventful back-and-forth, lost-and-found journey. It changed hands among royal descendants and routinely crisscrossed the English Channel. In 1942 it was “requisitioned” by Hermann Göring from a Rothschild baron. Three years later a French officer rediscovered it in a knapsack among other Nazi loot stashed on a special train bound for Berchtesgaden. He in turn gave it to a monastery back in Brittany, and it was only when the monks took it to an antiquarian bookseller to fund the repair of their storm-damaged roof that the book was recognized. Of the 12 items closely examined in de Hamel’s book, this is the smallest (“made for the hands of a queen”) and the only one preserved today in the country in which it was made.

Such is the “restlessness” of illuminated manuscripts, de Hamel notes. This explains why the item in his other standout chapter, the Hengwrt Chaucer, is to be found not in England but Wales. In a deft and original move, de Hamel stages a mock court case, airs evidence, and appoints himself a member of the jury to determine which scribe copied down the greatest work of Middle English literature, The Canterbury Tales.

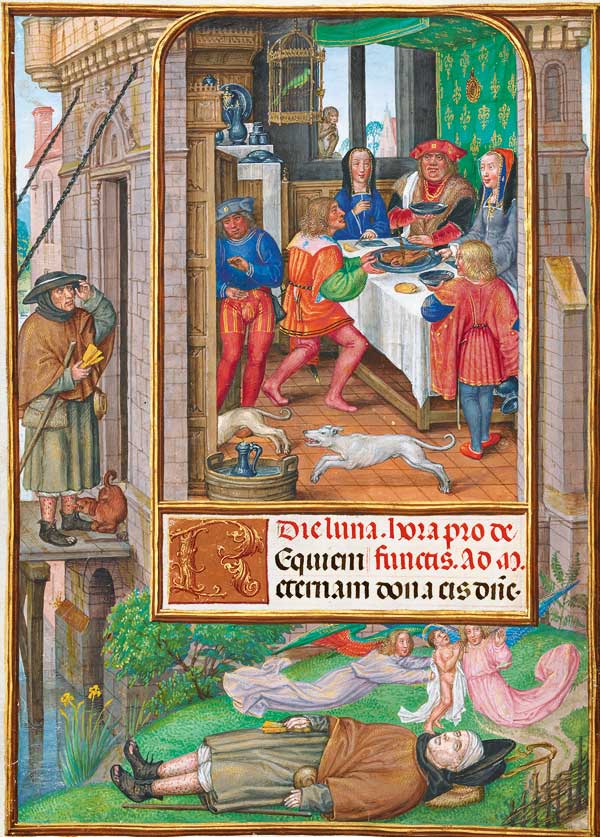

A page from the 16th-century Spinola Hours depicting the rich man feasting while the poor man begs in vain (although he ultimately gets into Heaven). [Penguin Press, courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum]

Doubters may suspect that this playful approach constitutes a brief respite from the rigors of scholarship, an interlude of freshness and creativity in an otherwise dry and starchy read. But they would be wrong. De Hamel’s book is erudite but on no account dull or forbidding. He dispenses with footnotes and decodes all jargon, leaving us neither irked at nor flummoxed by the mention of pandects, rustic capitals, and Visigothic minuscule. Whether leading us through a library to its vaulted depths or describing a manuscript—its history and its authorship, its pages and its binding, its handwriting and its pictures—he maintains a tone that is teacherly yet chatty. “Come in—really,” he says, slipping into tour-guide mode to present the 12th-century Copenhagen Psalter. “Sit beside me and let’s gaze in admiration for a moment. We won’t touch it: just look.”

If de Hamel’s book has a flaw it is this—not the many author-to-reader addresses, which may appear twee but are in fact endearingly quirky, but rather the conveyed impression and false hope of our being able to look and touch. “No one can properly know or write about a manuscript without having seen it and held it in the hands,” de Hamel tells us, and “nothing can compare with the thrill of excitement when a supremely famous manuscript itself is finally laid on the table in front of you.” Even though the book is beautifully illustrated with color images throughout, we readers are not there alongside de Hamel in screened-off reading rooms and cannot properly know these manuscripts or feel that incomparable thrill.

However, losing ourselves in de Hamel’s glorious Wunderkammer of a book is far and away the next best thing. His curiosity and enthusiasm are infectious and his dedicated sleuth-work and educated guesses are invigorating. When not awed by the sheer scope of his expertise or absorbed by his concerted efforts to decipher script or dissect scripture, we are diverted by his light flourishes and witty evaluations. In his eyes, the Book of Kells “risks being mobbed, like a pop star or a head of state.” Adam and Eve in one 10th-century manuscript are “shown naked and knobbly-kneed in the upper corner of the opening, brightly pink like newly arrived English holidaymakers on Spanish beaches.”

The book isn’t all unadulterated praise. Refreshingly, de Hamel punctuates his assessments with criticism where necessary. He highlights writing that is too rich or downright unreadable, pictures that are overly decorative or underdeveloped, and pages that have been rendered dark and shiny, “probably from overzealous handling and even pious kissing.” Not every manuscript is perfect. And yet all are at least minor miracles, works that, for the most part, are imbued with rare beauty, enduring wisdom, and enchanting strangeness.

Malcolm Forbes is a writer and critic in Edinburgh.