In September, the Met will open a retrospective exhibition of the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). Organized by the Louvre in Paris, where it broke all prior attendance records for a special exhibition after opening in March, it will be the first in-depth look in more than half a century at the career of the man widely considered the father of modern art.

A kind of teaser exhibition, “Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix,” which opened in July, will extend into the first half of the paintings retrospective. Why not wait and have it up concurrently? I don’t know for sure, but I suspect the head start was intended to highlight a too-little-known aspect of Delacroix’s work that might otherwise have been overshadowed amid such big-boned canvases as The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), a Götterdämmerung scene of the last Assyrian king calmly overseeing the slaughter of his courtiers prior to his own demise. It was a wise choice. This is a gem of a show that provides a succinct, engaging introduction to the artist and a revelatory look at Delacroix the draftsman, among whose achievements was to reinvent drawing for the modern era.

Organized by Ashley E. Dunn, an assistant curator in the Met’s department of drawings and prints, the show is drawn from a major gift to the museum of Delacroix works on paper. It comprises over 100 items: early student pieces, travel and preparatory sketches, copies of the masters, moody interiors of a Benedictine abbey in Normandy owned by his cousin, and a glowing pastel study of a sunset, a sky study worthy of those done by his British contemporary John Constable, an artist Delacroix admired.

Not many artists could withstand comparison with Michelangelo, the exhibition of whose drawings at the Met last fall still stands vividly in the memory. Delacroix does, however, in part because this is a very different kind of show. Michelangelo’s personality—his outsize genius, capacity for invention, and seemingly limitless output—dominated that exhibition. By contrast it is drawing itself that reigns here: its capacity for a wide range of personal expression and the way the particular qualities of each medium—pencil, ink, and pastel—contribute to a work’s emotional impact.

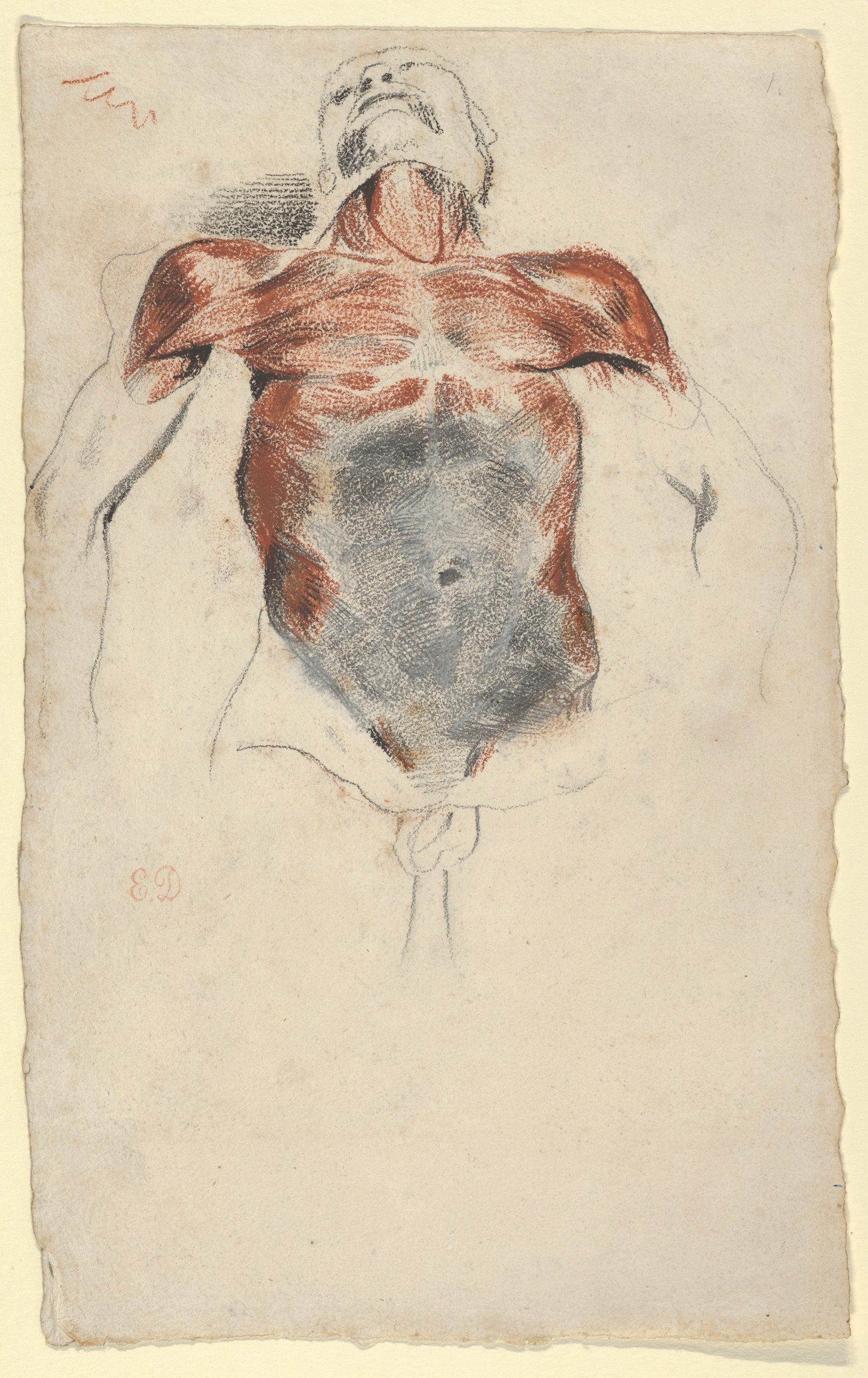

Like other aspiring artists of his day, Delacroix began his instruction in the traditional manner, by attending an art academy where he drew from the live model and absorbed the lessons of academic classicism—notions of ideal beauty and proportions inherited from antique art and the Renaissance—against which he and later artists would ultimately rebel. Some of these early figure poses and écorché studies of musculature feature in the exhibition, and they show how quickly he mastered human anatomy and complex attitudes.

Copying was also part of the curriculum of the day, one to which Delacroix responded with such enthusiasm that, frustrated by the limited selection of images available at the academy, he signed up to gain regular access to the prints and drawings department at the Bibliothèque Nationale, making copying the primary source of his artistic education. He believed it provided the real foundation of an education, since you learned not only the artist’s formal language but different drawing techniques and approaches, a point the exhibition makes extremely well in its juxtaposition of his copy of an image by Raphael with the original.

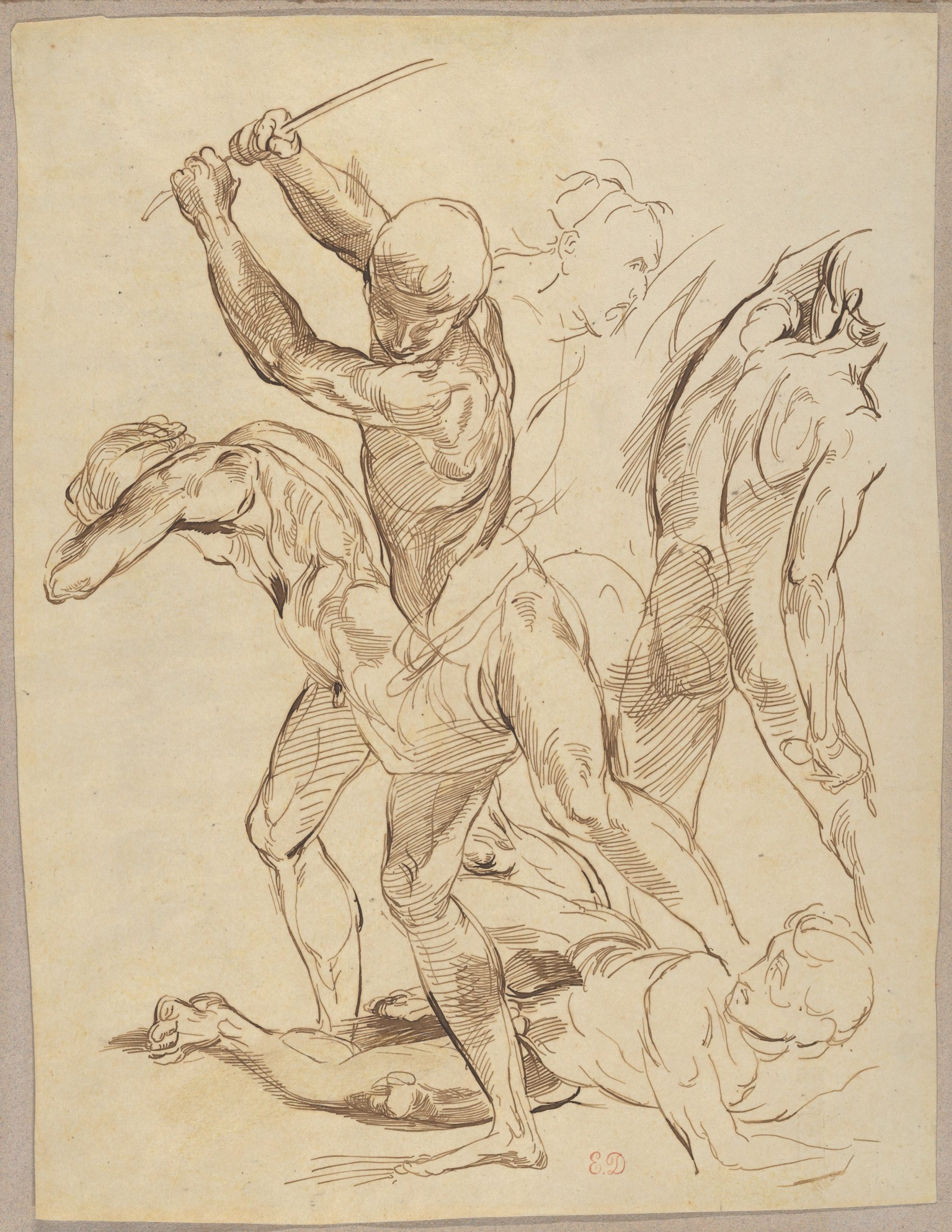

Well, not exactly the original: Delacroix worked from a book of engravings by the British artist Thomas Vivares that contains one showing four male nudes from a Raphael fresco in the Vatican, Michelangelesque in their dynamic, twisting poses and pronounced musculature. The bodies are described in tight, sometimes broken outlines, the interiors modeled with crosshatchings of various densities and lengths to endow the figures with a feeling of solidity, of three-dimensionality, of being situated in space. The process—drawing itself—is subordinated to the creation of the image. In his version, Combat of Nude Men, After Raphael (ca. 1823), Delacroix would seem to have copied Raphael/Vivares down to the last detail, including a passage in the source image where some crosshatching defining a part of the thigh extends beyond the leg onto the white of the page.

Yet, as the rest of the exhibition shows, in his copy Delacroix seems to have wanted to see how much more could be done with this particular approach, just how much more expressive this way of handling line could be for its own sake. So while contour lines continue to define the form, the interior modeling is much looser and freer, with more space between the individual strokes or hatch marks. Overall there is less emphasis on creating a credible illusion of human figures in space than on exploring and exploiting the possibilities of line.

Raphael was a lifelong inspiration, but Peter Paul Rubens was, as Dunn writes in the excellent catalogue, “a kindred spirit,” and here you can see exactly why. The three sheets of falling, twisting, and tumbling figures copied in the early 1820s from the Fleming’s The Fall of the Damned (1620) point directly to the Sardanapalus painting of a few years later. Delacroix, who was at once a revolutionary and a conservative, saw in Rubens a way of breaking free of the expressive straitjacket that was academic classicism to move into new areas of feeling, while keeping faith with the traditions of the past.

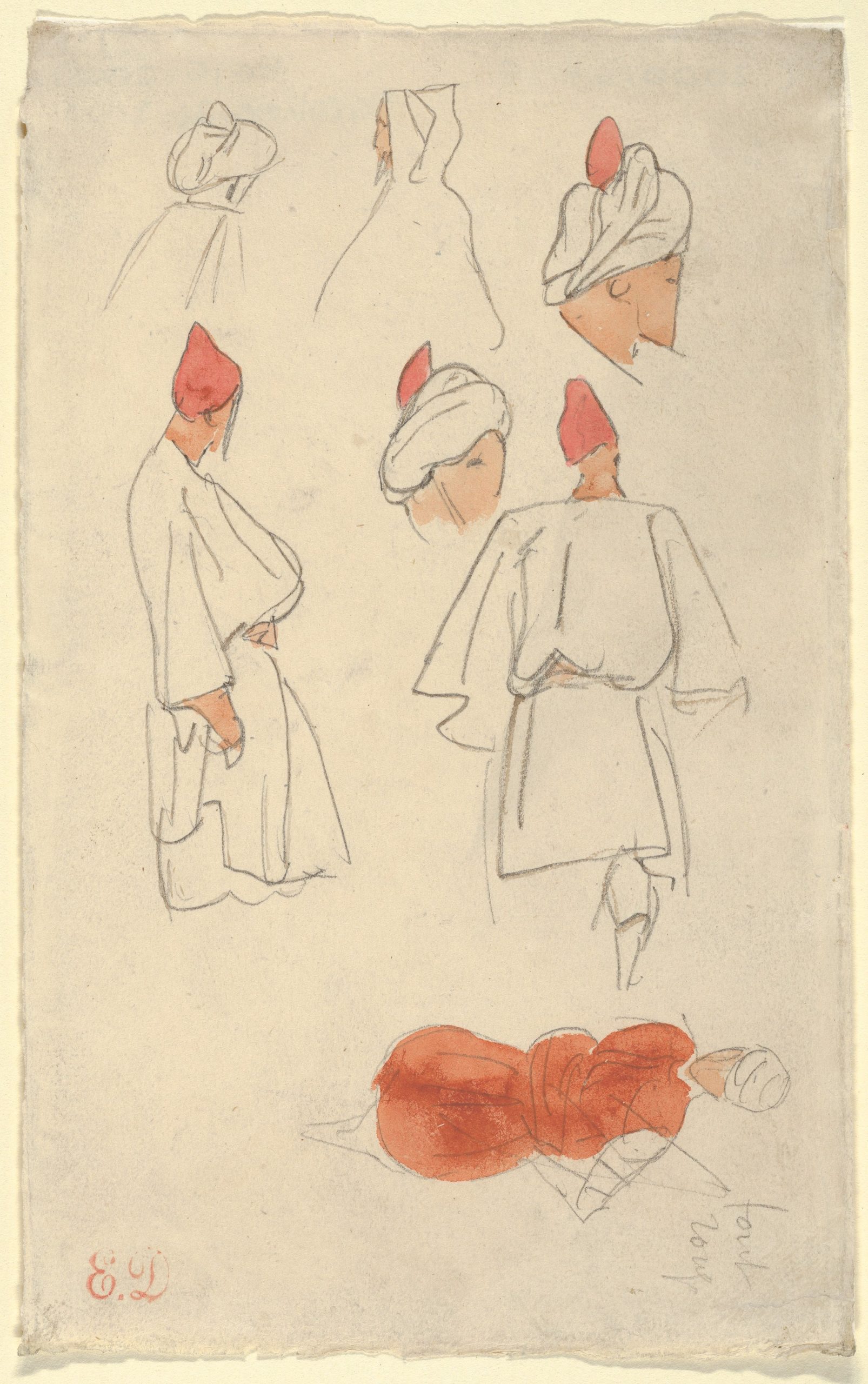

In 1832 Delacroix traveled to North Africa and Spain, and the roughly dozen works in this part of the show reveal him to have been a voracious and acute observer. They aren’t records of views and vistas so much as notations of details seen, probed with a pencil, and thereby committed to his visual memory. One sheet has several quick sketches of a Moroccan man’s outfit, another is a watercolor detail of a wall decorated with tiles complete with pencil notations naming the colors. Still another is a sheet with more than 20 studies of Arab physiognomy. It is an exciting display, offering that rare thing in an exhibition, a glimpse of the raw materials of an artist’s subsequent creations, in this case such seminal paintings as The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834), a harem scene that would later bewitch both Henri Matisse and, especially, Pablo Picasso.

If there’s a Delacroix Mona Lisa—a work with which he’s identified above all others—it’s probably Liberty Leading the People (1830), in which Marianne, the personification of the French nation, holds the tricolor aloft and, bare-breasted, urges a crowd of charging revolutionaries onward amid an array of prostrate corpses. There are preparatory studies for this painting—ink drawings of the fallen—as well as others. But the ones that command the most attention are what the artist called his premières pensées (first thoughts), rapid ink sketches capturing the earliest iteration of an idea. The central image in Studies of a Horse and Rider for ‘Heliodorus Driven from the Temple’ (1849-50), for a mural commission in the church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, is an equestrian subject like no other. Horse and what there is of the rider are rendered in short, sharp, calligraphic ink strokes, as is The Giaour on Horseback (1824-26), showing a character, in this case a Venetian horseman, from a Byron poem. Both are executed with a freedom that makes the liberties taken in the earlier Raphael copy seem positively tame by comparison. Line is no longer purely descriptive. Indeed, it is so hardly at all. Instead the various strokes and marks operate like so many independent vectors of energy, out of whose collective action an image emerges.

Though more resolved than those, Crouching Tiger is in a similar vein. Beginning very early on, Delacroix spent hours drawing in the zoo in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris’s botanical garden, and his mastery of animal anatomy is on display in many wonderful images in this show. Don’t miss, for example, A Lion in Full Face (1841), wherein the king of beasts has been reduced to essences: staring eyes, snout, and mane, this last little more than a halo of wiggly lines.

In Crouching Tiger, Delacroix vividly captures the tension of a cat poised to strike: the arch of its back, the swirl of its tail, its head thrust out and jaws apart, and particularly the positions of the front paws. But it is the way he does so that makes this the unforgettable work of art it is. The artist has applied the ink using both pen and brush, the former to model the animal’s body with quick crosshatchings, the latter doing most of the work and in two very different ways. A thin, fluid, concise line defines the overall form of the beast and hints at the speed at which the artist must have worked. Meanwhile, broad, thick, juicy strokes of ink model back, shoulders, and hind parts, while at the same time suggesting the cat’s pattern of stripes. Here we sense Delacroix reveling in the viscosity of the ink and the contrast between these dark, heavy passages and the lighter, linear ones. Part of what gives this work its power is that the image and the means used to realize it are held in perfect equilibrium.

In works such as these, Delacroix invents the modern drawing. The old aim of creating the illusion of three-dimensional form in space in which the medium was simply the means to an end and the sheet of paper nothing more than the ground or surface upon which it was inscribed gives way to a new impulse, one that set drawing on a path of renewal and revitalization. Beginning with Delacroix, line, the medium used to lay it down, and even the blank areas of the paper itself acquire an independent aesthetic life, as integral to the expressive effect of the finished work as the image they create. Vincent van Gogh’s scenes and portraits composed of reed-pen stipplings and scratchings, Edgar Degas’s heavily worked pastels of ballerinas, Auguste Rodin’s pencil-and-wash drawings from the model where the figure seems untethered to gravity, Matisse’s drawings and etchings of women and plants where contour lines both define a form and float freely in a space of their own creation—these and many more trace their lineage back to Delacroix’s liberating actions, now spectacularly laid out at the Met.