Many of the most headline-grabbing controversies in the history of football have been unrelated to the game itself. Take the fights in recent years over team names. At the college level, the NCAA in 2005 banned “hostile and abusive” names, even threatening the University of North Dakota and the state’s legislature that if they didn’t change from the Fighting Sioux to something else (eventually the Fighting Hawks), the university would be barred from hosting postseason competition. Only the handful of teams whose relevant tribes made clear they were unoffended—notably the Florida State Seminoles—were exempted. Other NCAA-targeted schools saw the handwriting on the wall and emulated North Dakota, becoming the RedHawks, War Hawks, Crimson Hawks, or other birds of prey.

At the professional level, the most conspicuous fight over a team name has involved the Washington Redskins. It’s not my purpose here to settle the controversy—except to join the late Charles Krauthammer in asking those who defend the team’s name whether they could imagine themselves calling an actual Native American who is their own size or bigger a “redskin” to his face. Of more immediate interest is John Eisenberg’s account in his deeply researched, surprise-on-every-page, and altogether marvelous new book The League of how the name originated nearly nine decades ago.

In 1931 the National Football League was floundering. Twelve franchises had disbanded in the previous four years, and the four that partially replaced them all failed too. The commissioner prevailed on his friend, Washington laundry owner George Preston Marshall, to found a team not in the nation’s then-sleepy capital but in Boston. In the prevailing practice of the day, Marshall’s new football club played in a major league baseball stadium—Braves Field—and adopted the baseball team’s name. When Marshall’s deal with the Braves eventually fell through and he moved his team to Fenway Park, he changed the team’s name while preserving the Indian theme and linking it to the new park’s major league franchise. Red Sox plus Braves divided by two somehow became Redskins.

The name remained when Washington boomed during the Great Depression and Marshall decided he at last could make money by moving the Redskins to his hometown. Once there, he doubled down on the Indian theme. A theatrical impresario, Marshall built halftime shows around a marching band whose theme song, “Hail to the Redskins,” featured lyrics like “Scalp ’um, swamp ’um, we will take ’um big score.” Things got even more extreme when Marshall, a fervent segregationist, decided to market the Redskins throughout the South as not just the southernmost team in the league but also as the last one to remain all white. For a time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the line “Fight for old D.C.” in the fight song became “Fight for old Dixie.”

Marshall made money from his extensive network of Southern radio and television stations even as the Redskins, devoid of talented black players, became the league’s doormat. Only in 1961, when his hand was forced by Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, did Marshall grudgingly begin the process of integration. Observe the federal laws on nondiscriminatory hiring or forget about playing in the new, spacious, National Park Service-operated D.C. stadium, Udall told him.

Of even greater interest on the subject of football names is what they tell us about the origins of the sport. Ever wonder why the game we call soccer is what the rest of the world calls football (and what we call football most other countries have no interest in)? As Roger Tamte explains in his comprehensive (but not bogged-downishly detailed) Walter Camp and the Creation of American Football, the American game began emerging in the 1870s from the primordial soup in which soccer, rugby, and the earliest glimmerings of a new sport all swam. When Yale invited Harvard to play football in November 1875, for example, Yale was all set to play soccer and Harvard to play rugby, both of them English games. They settled on rugby but also began what turned out to be an extended, incremental process of “messing with it, changing it,” with Yale student Camp at the heart of every development.

Instead of beginning plays rugby-style with a forward movement, American football players soon began kicking the ball backward to a teammate. This “snapback,” eventually accomplished by hand rather than foot, later became known as the “snap.” “Fullbacks” who stood 15 yards behind the line of scrimmage and “halfbacks” who stood 10 yards back soon yielded primacy to “quarterbacks” who, standing just 5 yards behind the line, could more reliably receive the snap. Touchdowns, which previously had no value except to give a team the right to kick a goal, were soon awarded points in and of themselves, fewer at first than field goals, but more in time. The extra point after a touchdown is the vestige of what used to be the game’s main scoring chance.

Most important, to keep teams from just sitting on the ball to the infinite boredom of spectators, Camp persuaded the representatives of the other Ivy League schools to require that they advance it at least 5 yards in three downs (later 10 yards in four downs). How to measure yards on the field? By marking lines so “it would look like a gridiron,” Camp suggested. The downs-and-distance rule, Tamte writes, turned the game into a “steady stream of compelling narratives”—a series of discrete plays, each designed and practiced in advance, creating the illusion that “watching a football game is like watching a military campaign.”

The innovations continued. In time, forward passes, previously banned, were allowed and the rounded, melon-sized ball was streamlined to make passing practical. Camp, who initiated most of the early changes in the game and codified them in annual rulebooks, was dubbed “the father of foot-ball in American colleges” by Outing magazine in 1886, even though he made his living as a rising executive with the New Haven Clock Company. But like others of his generation, Camp was slow to accept passing the ball as a legitimate part of the game. Glenn “Pop” Warner, for example, argued that “basketball techniques” like passing had no part in what was properly the “rushing or kicking” contest he and Camp had grown used to. Early passes were not allowed to cross the line of scrimmage and, if incomplete, turned over possession of the ball to the other team.

For the most part, football was football as we know it by the time the NFL formed in 1921. (A major exception: Players were not required to wear helmets until 1939 in the college game and 1943 in the pro league; some of them instead tried to protect themselves by sculpting massive man buns.) What’s especially revealing about team names in the early professional game is the extent to which they reflected what Eisenberg describes as its highly local, “industrial town origins.” Providence had its “Steam Roller,” Pittsburgh its “Majestic Radios,” and Decatur, Illinois, its “Staleys” (after the A.E. Staley Manufacturing Company, a starch maker). Even in the contemporary era of Raiders, Chargers, and Jets, remnants of the league’s early days survive in the Green Bay Packers (packers of meat, that is) and the Pittsburgh Steelers.

In the 1930s and for a quarter-century thereafter, when a core group of committed owners began to coalesce, the NFL—“paid football,” as it was derisively known—was not only secondary to college football, but also to baseball, horse racing, and boxing. As Eisenberg shows, over time the pro game was able to climb out of this hole because those owners—the Redskins’ Marshall, the Steelers’ Art Rooney, the Chicago Bears’ George Halas, the New York Giants’ Tim Mara, and the Philadelphia Eagles’ Bert Bell (who borrowed his team’s name from the emblem of FDR’s National Recovery Administration) embraced a strategy grounded in a subtle blend of competition and cooperation.

The owners fostered competition by continuing to modify their version of football after the colleges, content with their popular success, stopped innovating. Football had become dull, these owners realized. In 1934, for example, the losing team failed to score a single point in more than half the games. Usually at Marshall’s initiative, the NFL removed most restrictions on passing, moved the hash marks closer to the middle of the field so that the offense had more room to maneuver, and split the league into two divisions whose seasons culminated in a championship game.

Then, even as college football continued to forbid players from being freely sent in and out of the game, the NFL decided to allow unlimited substitutions. The result was the creation of separate offensive and defensive units whose players were less exhausted and more skilled at playing on one side of the ball or the other. “We’re in show business,” said Marshall, who was as innovative a marketer as he was intransigent on race. “And when the show becomes boring, you put a more interesting one in its place. That’s why I want to change the rules.”

Just as important as the innovations that made pro football more competitive with the college game was the cooperation among the owners that made this competition possible. Ending the open market in player signings that allowed wealthier teams to dominate year in and year out, in 1936 they followed later-commissioner Bell’s advice and instituted an annual draft in which the worst teams would have first crack at the best college players. To their credit, Halas and Mara, who owned the deep-pocketed Bears and Giants respectively, realized that although their clubs would suffer in the standings from the draft, the league—and thus their franchises—would endure only if teams were well-matched.

The best evidence that Bell and the owners were right came when a rival league, the All-America Football Conference, formed in 1946. It soon collapsed because one of the new franchises, the Cleveland Browns, was so dominant that fans outside Cleveland didn’t think their teams were worth seeing and fans in Cleveland, taking success for granted, didn’t buy tickets either.

The NFL absorbed the Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts and let the rest of the AAFC die. It also absorbed the lessons of Paul Brown’s success as co-owner and coach of the team that was his namesake. As told by Jonathan Knight in his breezily adoring Paul Brown’s Ghost, Brown’s innovations—studying opponents’ game film, dividing the team into specialized units with their own assistant coaches, and using substitutions to send in plays—turned coaches into field generals and the game into “an exercise in precision.” Brown would later coach and co-own the American Football League’s Cincinnati Bengals. He shepherded that team into the NFL as well.

The NFL also elevated itself by embracing radio and television, continuing to play during World War II after many colleges suspended their programs, and expanding west to California. The last move had the beneficial side effect of opening the league to black players when the commissioners who ran the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum told the Rams in 1946 that they could play there only if they integrated. “There were only so many good players, and when you eliminated half of them, it was tough,” said Redskins halfback Jim Podoley in 1960, one year before his own team finally became integrated in response to similar pressure from its new landlord.

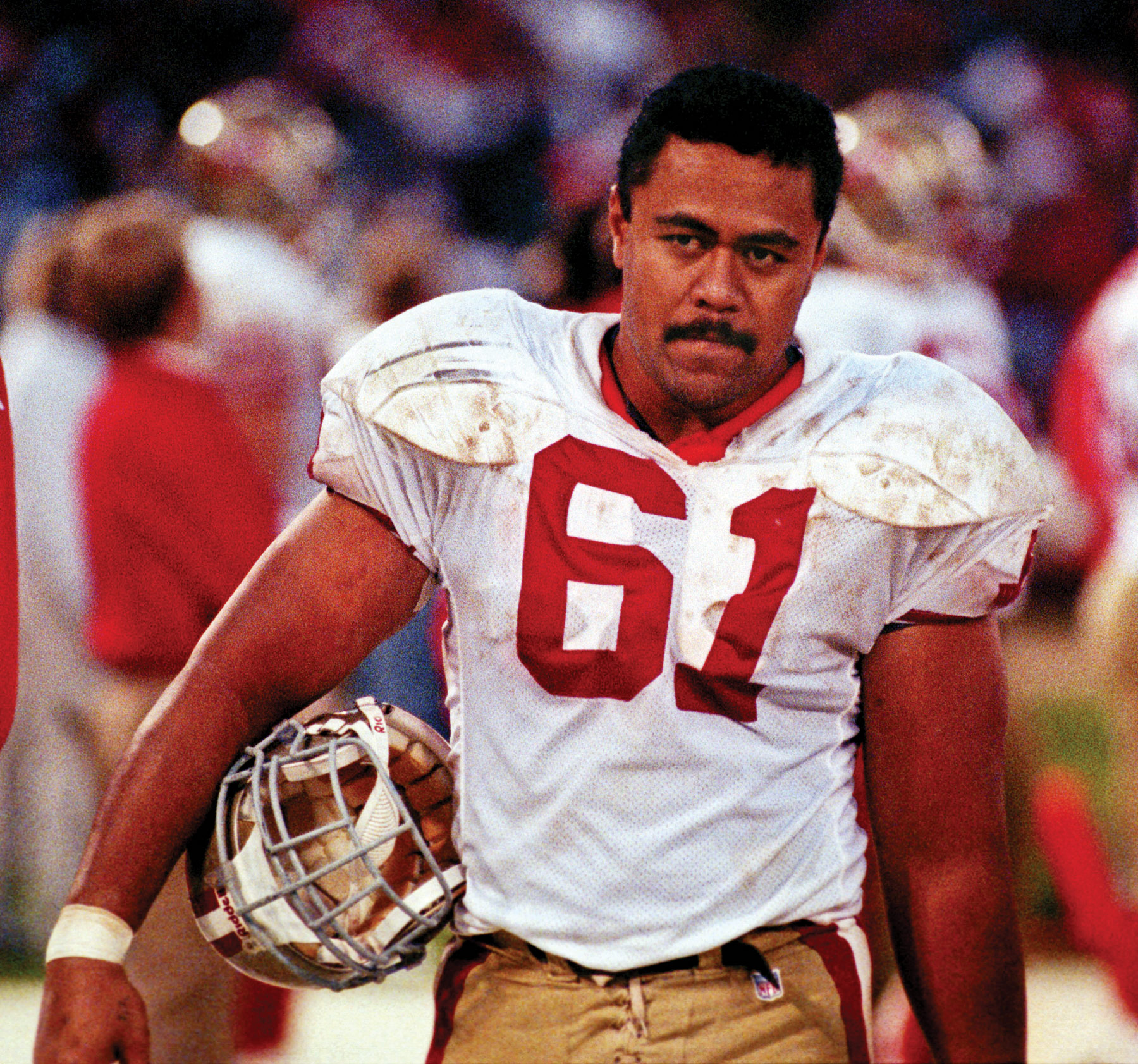

The 1960s were the decade in which African Americans became a major force in pro football—opening the door, eventually, for American Samoans, whose bittersweet saga of contributing the largest “number of athletes per capita” of any ethnic group in recent years while suffering disproportionately from their island culture’s physically reckless, all-in-for-the-team approach to the game is told in Rob Ruck’s Tropic of Football.

Ruck engagingly traces the cultural roots of Samoans’ distinctive suitability for football to fa’a samoa—the way of Samoa—which combines intense group loyalty with a zest for fighting. Until recently that meant villages trading blows with other villages. But under American colonial influence, the ethic was transposed to school football teams playing other schools, eventually yielding a harvest of hard-hitting, intensely team-oriented NFL stars like Junior Seau and Troy Polamalu. As recently has become plain, however, all too often the consequence of playing the game fa’a samoa-style is brain damage culminating in misery and even suicide, as in 43-year-old Seau’s tragic case.

The sixties were also the decade in which “pro football became America’s game,” as Jesse Berrett points out in Pigskin Nation, his cultural-studies-based (but non-scary) study of football and politics from 1966 to 1974. “Baseball is what we were,” columnist Mary McGrory observed in 1975; “football is what we have become.”

At a time when violence seemed everywhere out of control, with riots and assassinations at home and a frustrating war abroad, football thrived by being “violent but not sadistic,” in Berrett’s phrase—“precise and bruising” in Life magazine’s equally pithy description. Conservatives loved football’s raw masculinity and “meritocratic traditionalism.” Richard Nixon, for example, was a true fan who also saw that publicly embracing the game was a way to connect with previously Democratic Southern whites and blue-collar Northerners. But even Nixon’s liberal opponents, Hubert H. Humphrey and George McGovern, realized that their best endorsers were football players who were “at once celebrities and regular Joes.” It fell to novelist Don DeLillo to get the game’s resonance with the spirit of the age exactly right. Football is “not just order but civilization,” he wrote in End Zone: the leashing of humankind’s aggressive nature by rules, referees, organization, and self-discipline.

Merging with the 11-year-old upstart American Football League in 1970 also helped the pro game. The AFL didn’t make the same mistake as the AAFC: It not only drafted college players to keep the league competitively balanced but also distributed revenue from its national television contract to all teams. The new league added Southern franchises, put players’ names on their jerseys, and allowed two-point conversions, all of which were innovations the NFL adopted after the two leagues merged. The cherry on top, as Dave Anderson chronicles in his newly back-in-print reporting classic Countdown to Super Bowl, was the 1969 championship game in which the AFL’s underdog New York Jets defeated the NFL’s previously dominant Baltimore Colts.

Racial integration came late to the NFL but in a torrent when it did. Rising at an accelerated pace after the merger with the AFL, the percentage of African American players in the league eventually reached its current level of about 70 percent. As it happened, full integration’s late arrival overlapped with the rise of major product endorsement deals for celebrity athletes—Hertz for running back O. J. Simpson and Coke for Mean Joe Greene in football, Nike for Tiger Woods in golf and Michael Jordan in basketball, and so on. The result, Howard Bryant argues in his all-too-discursive but often on-the-mark book The Heritage, was that black stars became reluctant to embrace controversial civil rights causes that would jeopardize their appeal to white consumers.

Earlier black stars like Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, and Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown (subject of a fine, albeit leftish, new biography by Dave Zirin, Jim Brown: Last Man Standing) tended to speak out on racial issues. This practice declined as lucrative endorsements became more common, a trend that to some degree has been reversed by athletes’ responses to the recent police shootings of black men and boys in Ferguson, Missouri, and elsewhere—not to mention Nike’s decision to feature the protesting former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick in its latest “Just Do It” advertising campaign.

Newly outspoken players had no idea what an uproar reviving “the Heritage” would trigger. As Bryant points out, the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center not only made the soldiers who fight overseas wars objects of veneration at football games, it did the same for first responders at home, especially police officers. For a player to kneel or raise a fist as the national anthem is sung was seen by many fans—especially white fans—as slurring the flag the soldiers fought under. To aim the protest at the police was to insult officers in what had become their ceremonial backyard.

When Kaepernick sat during the anthem before the first two exhibition games in 2016, hardly anyone noticed. Only about a dozen other players emulated him that year, and then just occasionally. It took the president of the United States to light the match that ignited the firestorm. “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects the flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired,’ ” Donald Trump told an Alabama crowd in September 2017.

Most commentators picked up on Trump’s attacks on the players; few noticed that the direct object of his ire was “these NFL owners” who, rejecting Trump as a suitor again and again since the early 1980s, had long disdained his efforts to become one of them. In 1983, Trump bought a franchise in the new United States Football League and soon organized an anti-monopoly lawsuit against the NFL in hopes of forcing the league to let him in. When the lawsuit earned the USFL only one dollar (actually $3.76 when triple damages and interest were added), the league folded. As Mark Leibovich recounts in his windy, overly personal, but often insightful new book Big Game, Trump then made unsuccessful runs at the New England Patriots in 1994 and the Buffalo Bills in 2014. Spurned yet again by the owners as a “scumbag huckster,” “a clown and a con man,” Trump hit back as a candidate and as president. His attacks on the owners for not cracking down hard enough on the protesting players touched “a throbbing nerve on the right, making the NFL an improbable symbol of permissive leadership and political correctness,” Leibovich writes. “Football has become soft,” Trump sniffed.

To be sure, today’s team owners and NFL commissioner Roger Goodell, together the focus of Leibovich’s book, have responded to these and other new challenges with none of the adroitness or public spiritedness that Eisenberg discovered in the founding generation. Say what you will about the merits of the on-field protests; taking a knee in that setting takes guts. Bending the knee to Trump, as the owners have done, takes none. Nor, for that matter, does cringing when the players bark back, as the owners also have done.

“The Membership” aka “the Thirty-two” is a considerably older, stodgier, and more entitled group than the founders (80, Leibovich notes, is “ ‘middle-aged’ by Membership standards”). Unlike their predecessors, the Thirty-two feel little loyalty to their home cities. Stan Kroenke, named after St. Louis Cardinals icon Stan Musial, didn’t hesitate to leave behind generations of devoted fans and move his hometown team to Los Angeles. Nor did Mark Davis blink before leaving passionate Raider enthusiasts in Oakland after Las Vegas flashed “a near-billion-dollar stadium deal . . . like a high roller dangling a C-note at a strip club.”

Owners also are prone to making retro remarks to players, like “You guys are cattle and we’re the ranchers” and “We can’t have the inmates running the asylum.” With so much money at stake, Thomas George shows in Blitzed (an example of a worthy article pumped up to book length), rookie quarterbacks are often drafted higher than they should be and shoved into starting assignments prematurely, lest jersey sales and local ratings flag.

Even Tom Brady—Tom Brady!—was hung out to dry by New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft when he decided to appeal his suspension for allegedly deflating the footballs used during the first half of the 2015 AFC championship game. Describing the goosebumps he felt when he was accepted as a member of the Thirty-two, Kraft declared, “we won’t appeal” because “I don’t want to continue the rhetoric.” “What the f—?” Brady exclaimed to NFL Players Association executive director DeMaurice Smith, according to Casey Sherman and Dave Wedge in their generally persuasive pro-Brady book 12: The Inside Story of Tom Brady’s Fight for Redemption. Generally persuasive because although at the end of the supposedly deflated-ball first half the Patriots led the Indianapolis Colts 17-7, they outscored them 28-0 in the second half with undisputedly pumped-up balls.

The public-relations problems the NFL created for itself with its awkward handling of the players’ protests and deflategate are as nothing compared with the long-term threats to the viability of the game from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and changes in the broader culture.

Starting on September 28, 2002—the day when the autopsied brain of a dead ex-NFL player was first found to bear evidence of CTE—a massive amount of scientific research began to accumulate suggesting that not just severe concussions but also the cumulative effects of many routine hits can damage the brain in ways that may later bring on CTE, ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, dementia, severe cognitive impairment, and other diseases.

After scientific research and especially bad publicity forced its hand, the NFL finally began taking head injuries seriously as a medical problem with implications both for how the game is played—helmet-to-helmet tackles were banned, and then in time for the current season all helmet-first tackles were; kickoffs were moved forward to the 35-yard line; and players were forbidden to make a running start before the ball is kicked. How injured players are handled has changed, too: “Shake it off” was out; “no-go” for games and practices without an okay from an independent neurologist was in.

To be sure, there’s a lot that we still don’t know about football and the brain. Are there contributing factors—genetics? steroid use?—that explain why some former players suffer severe brain damage in later life while most do not? Did it “impact Aaron [Hernandez]’s behavior” when the former Patriots tight end, afflicted with CTE in his mid-20s, murdered a man in 2015 and then killed himself in prison two years later? “To suggest it didn’t would be ridiculous,” argues Hernandez’s lawyer Jose Baez in his troubling book Unnecessary Roughness.

Looking forward, are there ages at which, because the braincase is still hardening and necks are still thickening, playing organized tackle football should be forbidden? Would additional rules changes, like banning the three-point stance for linemen that places their heads directly in the path of collisions, make the game measurably safer?

The brain-damage issue aside, marked as it is by the NFL’s long concealment of important information from its own front-line, in-the-arena employees, it’s worth remembering that professional football players are just that, professionals: grown men who choose to embrace a violent career in hopes of receiving massive compensation. As Nate Jackson, an ex-player who lasted six seasons in the NFL (about twice the average), wrote in a typically lyrical passage from Slow Getting Up: A Story of NFL Survival from the Bottom of the Pile, professional players are “pulled toward the mayhem. . . . [T]he smell of grass and sweat: sacraments for bloodshed.” Still, he added, when the money is gone, “there is no incentive to continue. There’s a reason why you don’t see grown men at the park in full pads playing football.” It’s the same reason more and more parents are steering their kids into different sports. Even ex-NFL stars Troy Aikman, Brett Favre, and Terry Bradshaw have said that knowing what they now know they’d want their sons to stay away from the game, at least for a while.

Evidence of life-ruining injuries aside, why do football and other sports wax and wane in popularity? Michael Mandelbaum, in his deeply thoughtful 2005 book The Meaning of Sports, argued that during most of the 20th century baseball was America’s leading sport because it served as a pleasant reminder of an agrarian past for city dwellers who often were just a generation or two away from the farm. Football, according to Mandelbaum, was the right game for the mid- and late-century urban industrial nation. As with modern life in general, and in sharp contrast to baseball, football is “played by the clock” and in disregard of weather. It was, he wrote, “the sport of the machine age because football teams are like machines, with specialized moving parts that must function simultaneously.”

Not football but basketball, with its free-flowing, networked action, may soon come to dominate the age we live in, Mandelbaum argued. Today he might add that although basketball is intensely physical, it’s seldom debilitating—basketball players bang hard, but it’s shoulder-to-shoulder and elbow-to-chest, not head-to-head. NBA owners in particular have avoided confronting players about pregame protests, knowing that it takes two to rumble and in the absence of fight-club-style publicity, the media, the public, the players—and the president of the United States—are less likely to turn up the volume. A 2013 ESPN survey found that basketball has already surpassed football (and everything else) as kids’ favorite sport to play, and the NBA generates far more action on Twitter than any other professional league. Grownup spectators still rank football first, but as of a January Gallup poll, just 37 percent do so now, down from 43 percent as recently as 2007. NBA ratings are up and NFL ratings down, fewer boys are playing football in youth leagues, and so on.

Still: Football’s reign has not yet ended. Between them the current generation of NFL owners possess 20 of the world’s 50 most valuable sports franchises, according to Forbes. But after the real work of building the league was done by Rooney, Halas, Mara, Marshall, and Bell and carried on by Bell’s successor as commissioner, Pete Rozelle—the names we’ll remember long after the Kroenkes and Davises pass from the scene—how could the Membership not thrive? As offensive lineman Eric Winston notes, “Hey, even the worst bartender at spring break does pretty well.”