Trying to understand a novel by scrutinizing the life of the novelist is considered poor form these days — and for good reason. (It’s fiction, after all.) But when you write a novel about suicide and then ritually disembowel yourself in public, certain exceptions must be made.

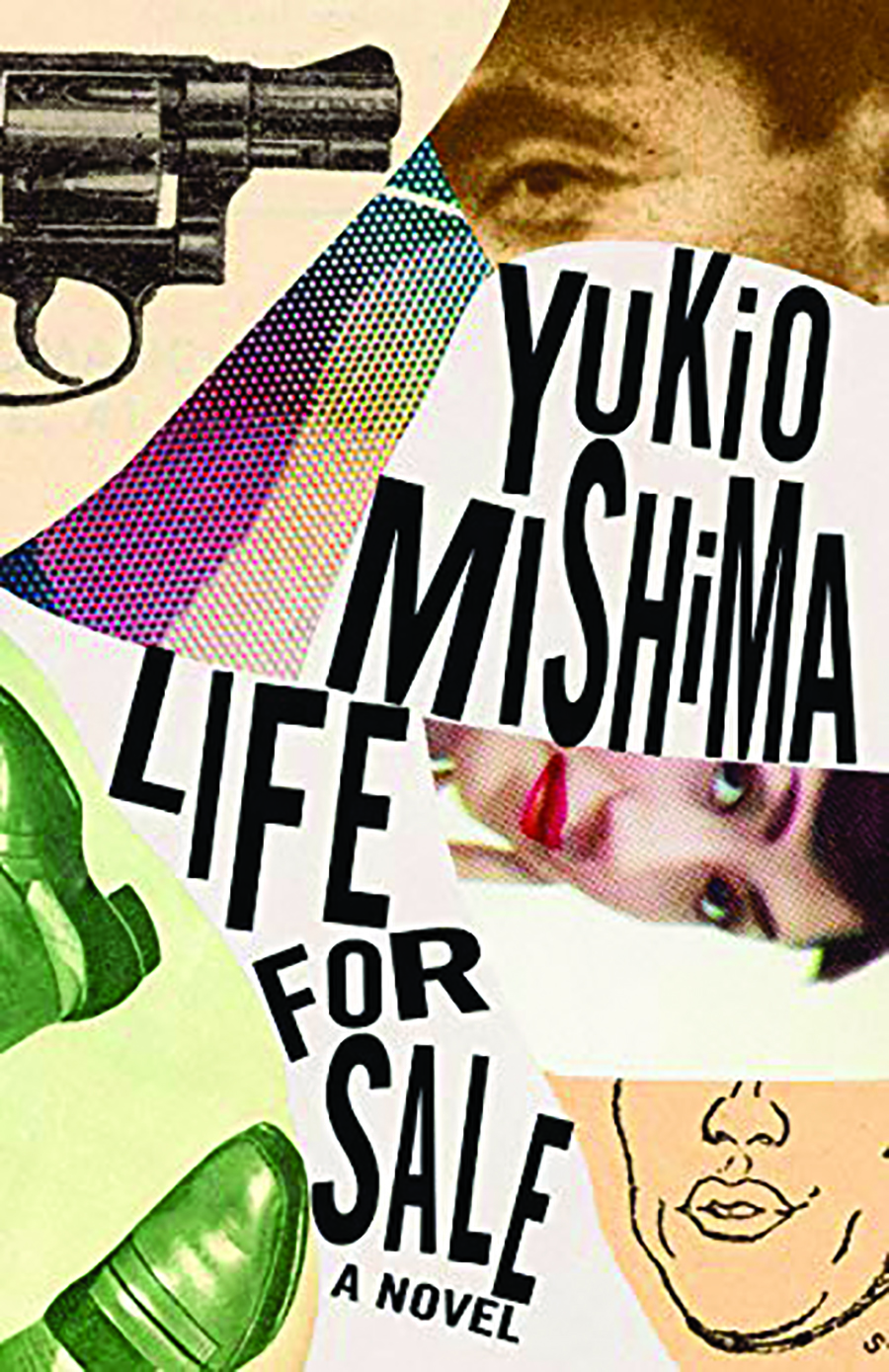

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) and his newly translated 1968 novel Life for Sale are the beneficiaries of this exception. By now, Mishima is at least as well known for his outré death as for his fiction. He might have been a Nobel Prize winner if he had chosen to die quietly of stomach cancer in very old age like a normal Japanese person. Instead, after an early mid-life crisis involving nationalist neomilitarism, oiling up his torso, and lifting weights, he stormed a Tokyo barracks with a half-dozen similarly lubricated followers and delivered a speech calling for the soldiers to rise up against Japan’s democratic government and swear allegiance to the emperor. The soldiers heckled him off the podium just five minutes into an intended half-hour speech, and he retired to the commandant’s office to gut himself like a mackerel.

The self-slaughter at the center of Life for Sale is far less spectacular. The hero, Hanio, is a Tokyo advertising man in his 20s who decides to die not because of depression or crisis but because he lacks any particular reason to continue. “You have as much heart as a vending machine,” one character tells him. Hanio agrees enthusiastically. He first gobbles sedatives on the Tokyo subway, but after waking up alive, he hits upon a weirder method — he writes one last ad, this one a classified. “Life for Sale,” it reads. “Use me as you wish. Discretion guaranteed.” He then waits for someone to show up at his apartment, make him an offer for his life, and choose an end for him.

All respondents to such an ad today would be perverts. (Think of Armin Meiwes, the German computer technician who in 2001 placed an ad seeking a young man “for slaughter and consumption.” He turned away two initial applicants and ate the third, penis first.) But Hanio’s callers are a higher class of deviant. The deaths they have in mind all involve Hanio undertaking what amount to suicide missions — mysterious little errands whose most likely outcomes are the errand boy’s demise.

The prospective buyers are all shady, like Philip Marlowe clients. They lie and steal, but they all pay. One wants a woman dead and enlists Hanio to seduce her, get caught in the act by her gangster lover, and be killed along with her. Another sends him to sell stolen property, a rare entomology text with details on how to extract poison from the shell of a beetle. Another client, a young boy, hires Hanio to be the captive sexual plaything of his mother, who craves human blood. The adventures are short and episodic, reflecting the novel’s origins as a series in a Japanese skin mag. It is written as hard-boiled entertainment and succeeds.

The irony of the novel, and the source of much of its unexpected humor, is that Hanio’s indifference to death brings him sex, money, and adventure — the only real life he has ever known. His real life doesn’t begin until he decides, “on a complete whim,” to end his normal one. He becomes an assassin, a spy, a lover, and a surrogate father. Trading his salaryman’s life for no life at all turns out to be a shrewd deal, particularly because the errands keep failing to kill (or at least, failing to kill him). Instead, he finds himself well-paid, sipping brandy, and bedding beautiful women like some kind of James Bond figure — wondering what his colleagues at the ad agency would think if they could see him now.

Life for Sale is not a profound book, and some of its wisdom is superficial in an adolescent, Dead Poets Society way. (“All that mattered was to live each moment of life as it came, to savor it fully and for as long as it lasted.” If there were more than a few lines like this, suicide would be a deliverance.) But the story does feel prescient, and Hanio’s loneliness and existential gloom, as well as his redemption, strike a modern reader as familiar. The nihilism is modern and Houellebecqian. The generation of Mishima’s parents fought for the glory of a god emperor; the postwar Japanese salaryman worked for his corporation and, in his free time, perhaps an evening at a pachinko parlor. If you think the sexless drone-lives of millennial gig workers are depressing, consider that if you drive an Uber, at least you get to set your own hours.

Another Mishima story, “Patriotism,” written in 1960 and filmed two years before Life for Sale (with Mishima himself starring and directing), features a military officer who commits hara-kiri, just as Mishima did in real life. (Mishima called it his “favorite story” and the officer’s disembowelment a thing of beauty “such as to make the gods themselves weep.”) Reading these two works together is like watching a man who is contemplating two very different ways of snuffing himself out: in a violent and grandiose rite or in a joyful series of adventures. Hanio is a more likable character than the officer, with such human traits as hypocrisy and a sense of humor. But things end badly for him, which is to say they do not end at all. Several deaths later, Hanio is still alive, and some of his clients have turned on him. And what could be more pathetic, for someone cursed with suicidal thoughts, than to be pursued by people intent on ending your life on their terms instead of your own?

Mishima evidently made up his mind about which fate was preferable. What a mess.

Alan F. Mordrick is a writer in New York and frequent visitor to Japan.