When the Supreme Court announced in June that it would hear the case of Friedrichs v. California Teacher Association, it sent shockwaves through organized labor. The case involves whether the nine justices should overturn a 1977 precedent called Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that allows public sector employees to be forced to support a union as a condition of employment. About half of the 14 million people in unions nationally are public sector employees. Overturning Abood could result in millions of them dropping their membership. Lead plaintiff Rebecca Friedrichs spoke with the Washington Examiner about her involvement in the case.

Washington Examiner: So what is your background? How did you get into teaching?

Friedrichs: I started dreaming of being a teacher when I was a kid. I just always loved working with little kids, so that’s what got me into teaching. It has been a very rewarding career. I’ve enjoyed it very much.

Examiner: Why California? Why not somewhere else?

Friedrichs: Well, I was born and raised in California. My whole family is here. I teach about 30 minutes north of where I grew up. It’s the same county.

Examiner: You had to know when you were accepting a teaching position that it was a unionized workplace. How did you feel about that at the time?

Friedrichs: Actually, I didn’t know that until I was student-teaching. I had no Idea. When I went into college and decided to become a teacher nobody ever mentioned it. I had no idea I would be entering a unionized workplace. Once I had finished my bachelor’s degree and was working in student teaching, it was my master teacher who educated me about teachers’ unions.

The reason she told me was because … next door to us there was a teacher who was, in my estimation, abusive towards her students. She was very impatient and would yell at them all of the time. She would grab them and look at them in the face and scream at them. They were little 6-year-olds and I was terrified of her, and I was 22 at the time. So I asked my master teacher, “what can we do about this horrible situation? Can’t we talk to the principal about this?” That’s when she sat me down and talked to me about unions and teacher tenure and how difficult they made it for districts to rid themselves of teachers who have become ineffective or, in this case, abusive. So that was my first time learning about teachers’ unions.

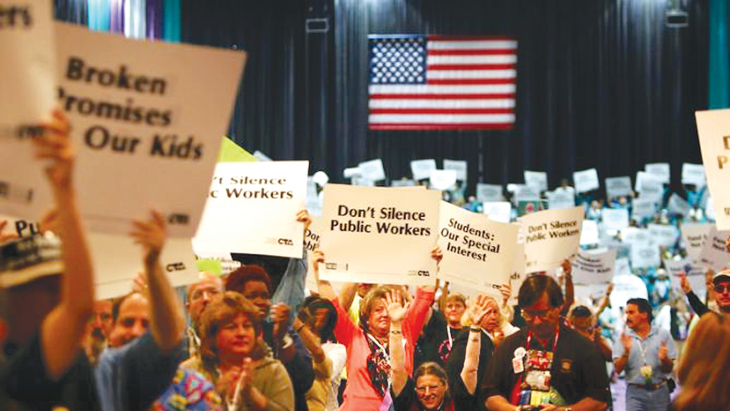

Once Friedrichs finished her bachelor’s degree and was working in student teaching, it was her master teacher who educated her about teachers’ unions. (AP Photo)

Examiner: What exactly did you find that the union did for the teachers? Did you find that they made things better or worse?

Friedrichs: On the positive side, the only thing I can point to is wages. They raise wages constantly, although it is a single-salary schedule. In other words, if you are outstanding, you don’t make more than the person next to you who is lazy.

That is really the only positive I can come up with. I mean they help with ensuring you have recess break and things like that. But really my experience from the beginning has been mostly negative with the teachers’ union. They come to our mandatory staff meetings and put pressure on the teachers to be political boots on the ground for union causes. Because I stand pretty much in direct opposition to most of their politics, I have never been appreciated by them. For example, when I was a young teacher, they were putting pressure on all of us to fight against vouchers. There was a movement in California to try to pass vouchers so that parents had a choice in education. The union would only give teachers one side of the story. The union would come in and say that this is going to destroy your job, destroy public education and you’ve got to fight against this.

As an independent-minded person, I went out and did some research, went to debates on the issue, and read up on it. I decided that I was for the vouchers. It sounded like a way to save tax dollars and to give parents choice. So, we’re at a staff meeting and here I am a young teacher and they’re putting all of this pressure on us to sign up and do phone banking and knock on doors and I said “No thank you, I’m not going to sign up.” I said I was for vouchers. They started calling me names. I was a radical right-winger because I dared to stand against union politics.

There is this undercurrent of fear and intimidation. Teachers are afraid to speak out about their own personal thoughts or beliefs if they stand in opposition to the union. So people just sort of go along to get along.

Examiner: Was it just simply pressure or was their some other way the union punished people to keep them in line?

Friedrichs: It is pressure and then if you don’t do what they want, they ostracize you. It is kind of like a middle school clique. If you don’t do what they want, then you are not in the clique. You are ousted. You are ignored. That year I didn’t sign up to help with the vouchers, I was treated like a second class citizen by the ones that were involved in that push.

Unions are kind of like a middle school clique. (AP Photo)

Examiner: Did the union ever involve itself in any way with your work in the classroom? Did having a union affect how you taught the students?

Friedrichs: They don’t come into the classroom while I’m teaching, nothing like that. But because of collective bargaining, they impact a lot of issues on campus and within the classroom. The unions lobby for things like tenure, which makes it very hard to fire a poor-performing teacher. They also fight for the grievance process. I call it a union one-two punch … If you a have problem teacher or any issue with a teacher, the administrators’ hands are tied. There just isn’t much they can do to fix the situation. That ends up impacting the classroom.

Examiner: Was there any sense that the unions had any positive impact on the quality of education the students were receiving?

Friedrichs: No, in my opinion it was negative. When you fight for the rights of teachers based on the number years they have been there rather than on their quality, children end up hurt in that process. I have watched as outstanding teachers have been laid off because of the budget and they don’t have as many years. But they’ll keep other teachers simply because they have been there for a long time.

Examiner: How little “d” democratic is your union? To what extent did the teachers have control over what it does?

Friedrichs: I actually served for three years on the executive board of the union in my district. I thought certainly if someone comes in and speaks common sense then we can all do what is right for teachers and kids. Here’s what I learned: The union tells the American people it speaks on behalf of all teachers, but really the union speaks on behalf of itself. I believe it is because of the automatic dues-paying regime (from teacher pay checks to the union, a common part of union contracts). The union leaders are not accountable to their members. So the union constantly takes positions that further the interests of the union leadership, but those positions often do not reflect the views of the teachers they claim to represent.

Members of a union sign in to receive voting cards. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Examiner: How often has your union held recertification votes to ensure that its members still want it?

Friedrichs: Never. I started teaching in 1988. I don’t know the exact year that the union for my district was first certified. It was some time in the 1970s. But I’ve never had a choice. I’ve never had a vote.

Examiner: Your Supreme Court brief estimates the total amount of membership dues CTA requires at about $1,000 a year. How big of a dent is that in a California teacher’s salary?

Friedrichs: It depends on where that teacher is on the payscale because your pay is based on your years of experience. I would say it is 1-2 percent of a teacher’s salary.

Examiner: The dues rate is the same no matter how long a teacher has been there?

Friedrichs: That’s right. The rate goes up arbitrarily, too. There’s no vote on raising dues either. They just raise them. They’re not raised after the teachers get a raise either. They just go up when the union needs more money.

Examiner: Under federal law you can request a refund on the portion of the dues that pay for things unrelated to collective bargaining. Did you ever try to do that?

Friedrichs: I do that now. That’s called being an agency fee payer. You lose all of the benefits of membership. In other words, you cannot be a member unless you pay the political portion of the dues. As soon as you say “I don’t want to pay for your overt politics,” you lose your voice and your vote in collective bargaining, even though you pay for the collective bargaining.

Every year you have to send a letter requesting that rebate and send it within a very short window of time. If it is postmarked one day late, you don’t get that rebate. I need to do that now, as a matter of fact.

Protesters try to block passage of right-to-work legislation that bans labor agreements that require employees to pay fees to the unions that represent them. (AP Photo)

Examiner: How much do you know about what the union spends its dues money on? Do you ever get to look at the books?

Friedrichs: They are required to send us something every year called a Hudson Notice that is supposed to lay out the chargeable and non-chargeable fees and where the money went. I read it every year and it is very vague. They don’t spell out where this money is going. They give categories like “human rights.” Well, what does that mean? Where is it going?

Examiner: What was the moment that made you think: Something has got change; I won’t stand for this anymore?

Friedrichs: I have to say it was the year when there were about six teachers being laid off (for budgetary reasons). I was still a union rep at the time, trying to have a voice. I went to the union meeting and I said, “Look, these teachers are outstanding. Parents love them. Kids love them. We don’t want to lose these teachers. If they are laid off, class sizes go up. This isn’t good for anybody. How about we go into collective bargaining and propose a 2-3 percent pay cut to save their jobs?” No one would even have a conversation with me. It was, “No, we cannot do that.” I said, “Why not? Teachers on my campus want to do this. Why don’t we have a survey or a vote?” Still, the answer was no.

Finally, the union leader came up to me and told me not to worry about the teachers because the union was going to give them a class on how to obtain unemployment benefits. My jaw dropped. I said “Are you kidding me? They’re paying $1,000 a year and you’re going to teach them how to get unemployment? When there are teachers willing to take a cut to save their jobs?” They wouldn’t even listen. That was when I knew I couldn’t make a difference from within.

Examiner: How did you come to be involved in the Supreme Court case?

Friedrichs: I started writing editorials once I got fed up. I thought I needed to educate the public about what is really going on. One thing led to another and I met some education reformers, some really good people that care about kids. Pretty soon I found myself involved in this lawsuit.

Examiner: What has been the reaction from your teacher colleagues to your involvement in this?

Friedrichs: That has been the most surprising thing. I thought I would be totally ostracized and hated but it has been the exact opposite. Most teachers take me aside and thank me for what I am doing. They won’t say it out in front of anybody because of that fear and intimidation. But quietly, they cheer me.

Friedrichs’ case could have a profound effect on public sector unionism across the nation. (AP Photo)

Examiner: What has been the reaction from the union?

Friedrichs: At first, I was hearing some very hurtful things. They weren’t saying it to my face, but friends were reporting this is what they said. I had some silent treatment for a while. Lately, they have been very respectful. They don’t really say anything.

Examiner: Your case could have a profound effect on public sector unionism across the nation. You’d be really upsetting the apple cart, so to speak. Are you ready for that?

Friedrichs: Yes, I am excited about that. It is time to do what is right for the American people and our children.

Examiner: What do you say to the argument that strong unions are needed to represent workers’ rights and that security clauses and agency fees are a necessary part of that?

Friedrichs: In other words, I shouldn’t be a free rider? Well, I would say that the unions tell the American people that they are providing teachers and other forced union members with huge benefits, but I disagree with that. In my opinion, the union’s supposed benefits aren’t worth the moral costs. When the unions protect teachers that are no longer effective in the classroom or who have become abusive at the expensive of vulnerable children, I have a moral dilemma with that. I would say that it is time to put individual rights above that of the unions.

This article appears in the Oct. 5 edition of the Washington Examiner magazine.