For most of November and December, an unusual modern art exhibition down from New Haven didn’t seem to be getting its due notice. At least whenever I returned to these beautifully installed, dark back galleries of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the rooms holding Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light were never empty—but not quite crowded as they should be.

Wilfred, a Danish-born artist unsatisfied with the power of painting and sculpture to convey light and movement, came to America to pioneer a form of mechanical light art he called “lumia.” His best-known work commanded a section of the Museum of Modern Art for the final years of his life after the Modern, which still owns three of his works, commissioned from him Lumia Suite Opus 158, a bursting layered screen of colored light controlled by stained glass and a motor behind the wall, in 1963. (You can see it and decades more of Wilfred’s lumia at the Smithsonian until January 2nd.)

Lumia large and small—the “small” are wardrobe-shaped units in the Clavilux Junior series engineered to play hand-painted color records, the Clavilux being the light organ Wilfred devised to design and program lumia—demand our rapt attention. On one Clavilux Junior, an early model loaned from devoted collector Eugene Epstein, greyish brown blobs wobble for several minutes. “It looks like a sick lung,” one white-haired woman remarked to her smirking companion, during my first visit. She was right. But minutes later, they brightened and broke into reds, pinks oranges—and then deepened into rich blues as if the “lungs” had healed, burst into flame, and then gloriously drowned.

Unit #86, from the Clavilux Junior series, 1930. Carol and Eugene Epstein Collection. (Photo: Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

Every one of the Wilfred’s lumia has a fantastic-organic analogue. In his Elliptical Prelude and Chalice, a tabletop chalice-shaped clavilux which projects onto the museum ceiling twice every hour, we found the enormous eye of a benevolent giant staring down from another dimension. And were the rooms more heavily trafficked, we couldn’t have laid down on the museum benches and stared back until it turned off again.

Unit #50, Elliptical Prelude and Chalice, from the First Table Model Clavilux series, 1928. (Photo: Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

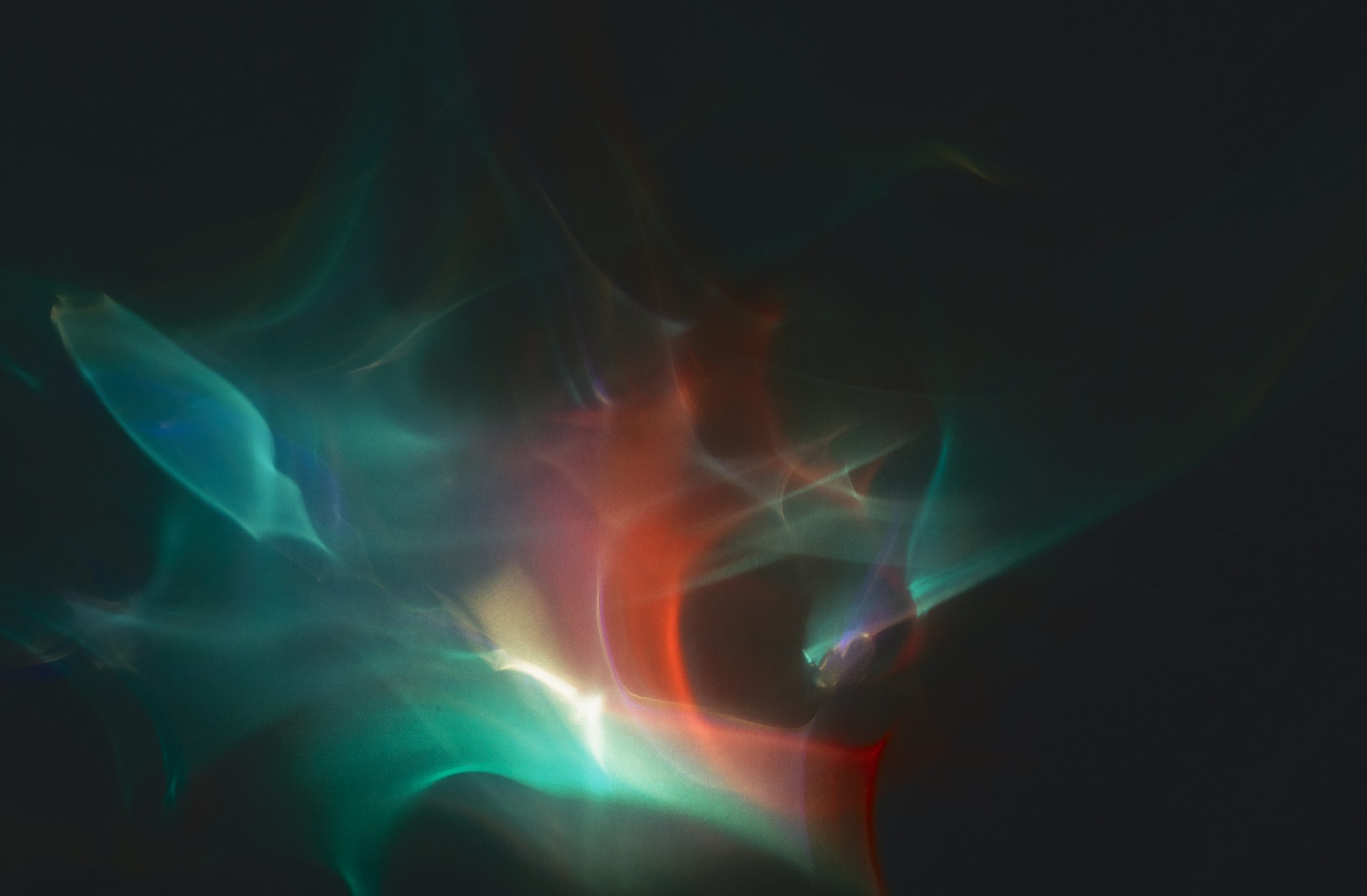

Lumia aren’t suited to a digital age attention span. Today’s art-appreciators, “They Instagram it and move on,” says Donna Stein, who curated the first Wilfred retrospective at D.C.’s former Corcoran Gallery in 1971. “But you can’t do that with him.” Only one of Wilfred’s works, Abstract Opus 91, or Firebird, stands still for the smartphone flash, fooling viewers like me into watching and waiting, determined to figure out how its red spearing blue and orange lightning might be imperceptibly moving.

Wilfred wasn’t contemporaneously famous, either. His mysterious art of making brilliantly colored streams and wands, wisps and bands of light dance and bend from within mechanized boxes—some for hours, some minutes, some for months—never really took off. Other artists claimed him as an inspiration, Jackson Pollock and James Turrell among them, but they didn’t imitate his methods.

Even so, you can see his influence in the culture: In the ’60s and ’70s, though, proto-hippies spaced out sitting on the floor in front of Lumia Suite. His obvious influence on the psychedelic aesthetic defies definition and documentation, but really, “all light shows were based on Wilfred,” said Stein.

Thomas Wilfred, Lumia Suite, Op. 158, 1963–64. (Photo: Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

Stein first met Wilfred in 1964 when she’d come to the Modern to meet with Dorothy Miller, the twentieth-century curator famous for her clairvoyant “discovery” of modern American artists. Stein wanted to write her doctoral thesis on the mysterious master of light, and he was there that day, tinkering away in the mechanical room behind his Lumia Suite.

I asked Keely Orgeman, a curator at Yale where three of Wilfred’s lumia live, and where the Smithsonian’s current exhibition began, about the maintenance challenges of the intricate, largely hidden, and technically outmoded works. “When Wilfred was still alive,” Orgeman explained, “he was regularly at the museum, checking on the condition of his work and consulting with the people who were helping to maintain it.”

The lumia’s exact rhythms demanded then, and still do now, obsessive upkeep—and in the case of the Modern’s Lumia Suite, years of collaborative restoration and rebuilding. These maintenance routines largely faded from memory after Wilfred’s death. And the maintenance is one reason the current retrospective, only the second large-scale Wilfred show since his death, won’t travel onward from the Smithsonian. Until New Haven’s three Wilfreds were found in storage nearly ten years ago, the Yale Art Gallery had forgotten about its lumia and their delicate care.

Wilfred was a profoundly secretive man. He doesn’t want us to figure him out. Visitors should, and mostly do, step into the shadows of Smithsonian’s Lumia unaware of his ideas and background. (He was an interesting fellow, both obsessed with Albert Einstein’s work and while a young man living in New York, was a member of a Theosophist sect called the Prometheans.) “Art is about mystery,” Stein says—and it helps, toward this end, that the lumia have to be shown in the dark.

What makes the Wilfreds so moving and unforgettable, is more than their morphing light shapes and all the strangeness of wandering through a dozen different machinemade dimensions of winding electric wisps and flashes. It’s also the fact of there being someone, or several someones, working to keep these lights turned on half a century later. A painting is a painting. It exists whether you know about it or not. Thomas Wilfred’s lumia exist today only if others know to take care of them.

I asked Donna Stein whether Wilfred would live on for another 50 years. “Oh, sure,” she said. A second generation, one for whom a wood-paneled monitor is just mixed media, was already re-inheriting his untraceable lines down at the Smithsonian.