In week nine, many NFL head and assistant coaches were dressed in camo-stylized gear that suggested military fatigues. At attention along the sidelines were even larger than usual contingents of color guards from the services, dress-uniformed law enforcement officers, and other first responders. Sarah McShane, a New York Fire Department EMT, sang the National Anthem so well it brought tears to the eyes. Fundraising for wounded-warrior organizations was extensively touted as an NFL Salute to Service, including in network advertisements that featured pro football stars giving testimonials to the armed forces. The National Football League, it was suggested to audiences, has something or other to do with protection of our communities, even, with national defense.

It was complete fabricated hocus-pocus nonsense. Or as Donald Trump would say in capital letters, it was FAKE NEWS.

The association of football with the services has always been perplexing. Coaches have military-like responsibilities, are addressed as “sir,” order their charges into a kind of battle-lite. But unlike actual members of the armed forces, NFL coaches take no risk, while being lavishly paid. Wrapping them in the American flag may be good public relations but does not turn NFL coaches into patriots—rather, it cheapens the dangers accepted by those who risk their lives in actual service to the nation.

Military flyovers at football games—there’s always a flyover for the Super Bowl, and an Air Force B-52 flew for the Vikings-Saints Monday Night Football opener—might make sense for the Pentagon as a recruiting tool, but should not be mistaken as suggesting the NFL has anything to do with protection of American liberty. Nor does the NFL have anything to do with the police officers, firefighters, and ambulance crews who protect communities. Sure, it’s pleasant for soldiers, sailors, and first responders to get to walk on the field before an NFL kickoff. But for the NFL and its broadcast-partner networks to flatter themselves with the reflection of real public-service heroes who take on genuine risks is superficial in the best case, and cynical in the worst.

Which brings us to the Salute to Service campaign, recently an annual NFL event. In a world of crass commercialism and rampant phoniness, the Salute to Service goes over the top to total, utter fakery.

The NFL will sell you the faux-fatigues gear that allows the wearer to seem a phony football coach and a phony soldier simultaneously: a make-believe daily double. I hope that no actual soldier or sailor would place such apparel on his or her body.

The league “does not profit from the sale of Salute to Service products,” its Salute to Service website reads. “Charitable contributions are donated to the NFL’s military nonprofit partners including the USO, Wounded Warrior Project, Pat Tillman Foundation and TAPS.” It’s not just that a football league boasts “military nonprofit partners,” again suggesting the NFL has something-or-other to do with national defense. It’s that the donations are crumbs from the table. In an enterprise with $14 billion annually in revenue, a dollar here or there is donated for sweatshirts, or trivial sums are donated based on scores of some NFL contests. Then the NFL expects to be applauded for its generosity.

Since 2011, the NFL says it has raised more than $17 million for wounded-warrior projects. In that period, the NFL has realized about $70 billion in revenue. The $17 million donated in the name of the armed services represents two one-hundredths of one percent of NFL revenue.

Using the most recent disclosures of the Green Bay Packers, the sole publicly owned NFL team, thereby the sole NFL team that reveals numbers, it is reasonable to estimate that since 2011, the NFL has realized about $10 billion in profit. The $17 million donated in the name of the armed services represents less than two-tenths of one percent of National Football League profit.

Public subsidies to the NFL since 2011 work out to about $6 billion, for stadium construction and operation, plus property-tax exemptions. The $17 million donated in the name of the armed services represents about three-tenths of one percent of the public subsidies the league has received in the Salute to Service period. The public gives the wealthy owners of the NFL $6 billion, and they show their incredible generosity by tossing 0.3 percent from the table to wounded warriors—and then claiming a tax deduction.

“What a great job by the league on Salute to Service, so generous,” NFL Network host Scott Hanson gushed Sunday as the ticker at the bottom of the screen showed about half a million dollars given by the NFL so far in 2017. That’s about one-twentieth of one percent of the public subsidy NFL owners will receive this season. As I write this sentence the ticker is at $885,195: not even one one-hundredth of NFL revenue this season. So generous!

I told NFL spokesman Michael Signora I was working on this item and needed data; he was responsive and helpful. Once I had the data I asked him for a comment on this question: “Why should the NFL be admired for such a tiny donation?” He did not reply.

Among many Veterans Day-oriented NFL statements: “The Indianapolis Colts will join the NFL’s Salute to Service by dedicating their Nov. 12 game to honoring military personnel and their families. At the game, the team will recognize 100 Gold Star families, distribute camouflage ribbons and American flags to fans and donate the proceeds of their 50/50 Raffle to military organizations.”

The Indianapolis Colts play in a publicly funded facility where the ownership family retains all game-day revenues, and other owners split the television proceeds: the public bearing the cost, the rich keeping the profit. In return, the Colts will give away camouflage ribbons and donate half of whatever’s tossed into buckets at a raffle.

This is just one of many examples from the phony, cynical annual exercise that the NFL—and partners Amazon, AT&T, CBS, Comcast/NBC, Disney/ESPN, Fox, Google, Twitter and Verizon—manipulatively call a “Salute to Service.” Hearing of the greed of NFL owners: Soldiers and sailors, please don’t decide to stop defending us.

In other football news, versus Oklahoma, Oklahoma State scored 52 points, gained 661 yards, and lost. The Saturday final of Oklahoma 62, Oklahoma State 52 was joined by USC 49, Arizona 35; Wabash 48, Alleghany 41; Notre Dame 48, Wake Forest 37; Kansas 42, Texas Tech 35; Arkansas 39, Coastal Carolina 38; Clemson 38, North Carolina State 31; Urbana 36, West Virginia State 35; with other scoreboard-spinning results.

In the Bedlam game, the Sooners and Cowboys combined for 114 points, 1,446 offensive yards, 62 first downs, and 164 snaps, versus 74 points, 645 offensive yards, 39 first downs, and 127 snaps in Denver at Philadelphia, the highest scoring NFL game Sunday. The third-quarter sequence in which a long Oklahoma State touchdown pass was followed almost immediately by a longer Oklahoma touchdown pass—two scores covering more than 100 yards in just less than a minute on the clock—is contemporary quick-snap college football in a nutshell.

Oklahoma Sooners WR Marquise Brown (5) hauls in a long pass in the fourth quarter during a college football game between the Oklahoma Sooners and the Oklahoma State Cowboys on November 4, 2017, at the Boone Pickens Stadium in Stillwater, OK. (Photo by David Stacy/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

The last decade or so of high-scoring college results traces to several factors.

One is now that recruiting classes are ranked by Rivals.com, college coaches seeking to appease the alumni and boosters during the offseason focus on offensive skill players, who generate stats and rankings in a way that linemen and linebackers cannot. Observing this, talented high school guys lobby to play offense, resulting in more offensive than defensive ability entering the collegiate ranks.

Another factor is that 7-on-7, unknown 15 years ago, now rules prep football. High school players spend endless hours in 7-on-7, where they practice completing passes but little else. Baker Mayfield’s 598 yards passing on Saturday, an unimaginable stat a generation ago, was mainly a result of him being a child of 7-on-7 leagues.

A third factor is that college clock-management rules—especially stopping the clock for first downs—result in more snaps than pro rules. As hurry-up offenses have become the norm in college, the clock rules are generating a big disparity in additional snaps, which result in more yards gained and points scored.

The fourth factor is tired defenses. A rule of football is that playing defense is more strenuous than playing offense; it’s a tad difficult to explain, but anyone who has ever been in pads understands this. For prior generations, a goal was to get your opponent’s defense tired by the fourth quarter, then pound the ball. Today, with uptempo offenses calling plays at the line to increase the number of snaps, defenses get tired quickly. In the second quarter, the Sooners and Cowboys combined for seven touchdowns and a field goal, because by the second quarter, both defenses looked winded.

The final factor is college’s different rules on linemen downfield and offensive pass interference. In college, actions are legal behind the line of scrimmage that would be illegal in the pros. In 2009, college football changed its rules to allow offensive linemen to go three yards downfield and block before the release of a forward pass, versus the NFL allowing a blocking only one yard downfield before a forward pass, and then only if the blocker is in continuous contact with a defender. The later standard in effect means that an NFL blocker can only hit a guy who’s on the line or in press coverage, whereas in college, linemen can go downfield and look for someone to slam.

The 2009 rule change, especially, led to the proliferation of the hitch screen in collegiate play. Defenses obsessed with containing hitch screens are nicely set up for stop-and-go moves that result in long scores. The hitch screen is not unknown in the NFL: New England uses it, and the Texans got a long touchdown off a hitch at Seattle a couple of weeks ago. But college rules make this action more effective, and since the hitch screen is football’s easiest pass to complete, one result is runaway collegiate scoring.

Stats of the Week #1. New Orleans opened 0-2 and since is 6-0.

Stats of the Week #2. The Buccaneers opened 2-1 and since are 0-5.

Stats of the Week #3. Washington’s last-gasp winning drive at Seattle—hardest place in the league to score—took four snaps to travel 70 yards.

Stats of the Week #4. Washington is 4-0 in regular season games at CenutryLink Field.

Stats of the Week #5. The Dolphins, sole NFL team without a rushing touchdown, just traded away tailback Jay Ajayi, who scored a rushing touchdown in his first outing with Philadelphia.

Stats of the Week #6. The Broncos are on a streak of being outscored 124-52.

Stats of the Week #7. Since the start of the 2016 season, the Jets are 3-1 versus the Bills, 6-15 versus all other teams.

Stats of the Week #8. At 7:06 Eastern on November 5, Alex Smith threw his first interception of the season.

Stats of the Week #9. First-half possession results in the Oklahoma-Oklahoma State contest: field goal, punt, punt, touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, punt, touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, touchdown, field goal.

Stats of the Week #10. Carson Wentz, rated zero stars by Rivals.com, leads the NFL with 23 touchdown passes.

Sweet Play of the Week. Denver leading 3-0, the Eagles had 1st-and-10 on the Broncos 32. Denver’s motormouth corner Aqib Talib had just been hit with a holding penalty, and was jawing mightily with the zebras—sweet time to hit him with some deception. The Nesharim lined up trips left, with Alshon Jeffrey the sole receiver on the opposite side, across from Talib. At the snap the line zone-blocked left; Carson Wentz play-faked left, then rolled right to loft a floater to Jeffrey for a 32-yard touchdown behind the still-jawing Talib, and the rout was on.

Sour Play of the Week. Dallas leading 7-3 with 1:30 remaining before intermission, the Chiefs had the Boys pinned on their 13, 3rd third-and-15. A three-man rush allowed Dak Prescott to take his time, and Dallas converted. Now it’s 1st-and-10 on the Dallas 34 with 1:03 left. Prescott was pressured in the pocket and rolled right. Both defensive backs on that side—Steven Nelson and the boast-a-matic Marcus Peters—made the high-school mistake of looking into the backfield, rather than guarding their man. Both came to a halt and simply stood watching Prescott, not noticing Terrance Williams of the Cowboys blow past for the 56-yard reception that positioned the hosts for a touchdown. After Williams made the catch and began to run, Peters, who boasts, boasts, boasts, barely bothered to jog in the opponent’s general direction. Sour for the Chiefs, who after a 5-0 start are now on a 1-3 stretch.

Sweet ‘n’ Sour Plays of the Week. Hosting the LA/A Rams, Jersey/A had the visitors backed up to 3rd-and-33 early in the game. Sweet for the home crowd.

Jared Goff threw a short curl to Robert Woods, who caught the ball with nine of the 11 Giants between him and the goal line—seemingly a hopeless position. Rams tackles Rodger Saffold and Andrew Whitworth hustled downfield to get blocks, several Giants only jogged in their general direction, and Woods went 52 yards for a touchdown on 3rd-and-33. Sour for the home crowd. Later, LA/A’s Sammy Watkins would get 10 yards behind the Jersey/A secondary for another long touchdown, though the corner covering Watkins was backpedaling at the snap. Very, very sour.

In Praise of November and December. TMQ’s favorite part of the year is the phase from Halloween to Christmas: leaves are turning colors, football is being played, turkey and stuffing are in the oven, guests are arriving, and presents are being wrapped in anticipation. This period lasts two months, so from my perspective, every year a person must get through five days for each one day of pure enjoyment during the holiday period. And now that period has begun.

Ahhh, fall in New Hampshire.

Colin Kaepernick Belongs in a Locker Room Not a Courtroom. The loss of Deshaun Watson to injury may seem to doom the Houston Texans this season. Why doesn’t Houston sign Colin Kaepernick? Any coach would rather have Watson than Kaepernick behind center, but that option is no longer available to the Moo Cows. Kaepernick plays roughly the same style as Watson, so he could fit into the Texans’ philosophy in a way that that he would not fit at, say, Green Bay. Given all the political tensions in the Texans organization, signing Kaepernick might jolt the team back into the playoff hunt.

Last summer, TMQ noted there was a good football case not to sign Kaepernick, since most teams were set at quarterback and no team was looking for a zone read guy. Suddenly there is a football case that favors Kaepernick: Several teams need quarterbacks, and Houston has been putting up points using the RPO style. So howze about it Texans?

BOLO of the Week. All units, all units, be on the lookout for the Seattle defense. The Seahawks have played two straight poor defensive games at home, where they are usually stout. A week ago, the Seahawks defense allowed 38 points by the (pre-Watson injury) Texans. This week the Blue Men Group held a 14-10 lead and had the low-voltage Potomac Drainage Basin Indigenous Persons offense backed up on its 30 with 1:34 remaining. Washington went those 70 yards for the victory in just four snaps, not even needing a time out.

On the game’s decisive snap, the Persons had 1st-and-10 on the Seattle 39. Big, fast wide receiver Josh Doctson lined up wide versus rookie corner Shaquill Griffin, who played poorly the week before versus Houston. Griffin was beaten badly for a 38-yard gain to the Seattle 1, then when Doctson fell, didn’t touch him. In college a ballcarrier who falls is down; in the pros he must be touched, and Griffin did not seem to know that. More important, Griffin didn’t seem to expect a deep pass route, though the clock was ticking and Washington had to reach the end zone. Most important, where were the safeties? Seattle’s famed Cover 3 was nowhere to be seen—no one gave Griffin help over the top on this key play, though Washington had to reach the end zone.

All units, all units, be on the lookout for the reputations of Julio Jones and Jimmy Graham. Jones dropped a perfectly thrown fourth-down pass in the end zone in the fourth quarter of Atlanta’s three-point loss at Carolina. Graham dropped a perfectly thrown deuce pass with 1:40 remaining in Seattle’s loss to Washington, and though the visitors ultimately won by three, a successful deuce would have altered the endgame dynamic.

Look Mommy, An Exhibit of BBC Retractions! Reserve your tickets now for the BBC Amusement Park, perhaps offering an exhibit in which park-goers can sit at a BBC news desk, stare into the camera, and blame America. If this is too hoi-polloi for your tastes, try the new Ferrari Land.

Hinkle Fieldhouse, home of Butler University basketball, in Indianapolis, Ind.

The Good and Bad of College B-Ball. College basketball tips off Friday. This is a fabulous sport: great performances, college-town enthusiasm, campus atmosphere. The men’s version gets a lot of well-deserved exposure on national television; the women’s version is high-quality too.

On your bucket list should be attending any college basketball game at the sport’s best historic arenas: Cameron Indoor at Duke, Hinkle Fieldhouse at Butler, and The Palestra at Penn. All are relatively small because they were built pre-war; have up-close intimacy to the court; and offer the feel of history. It’s worth attending a game in any of these, no matter who is playing whom, just for the experience. If you can’t make it to one of these magical places, attend a men’s or women’s college basketball game anywhere: You are unlikely to be disappointed.

The high quality and spirit of college basketball are in stark contrast to the sport’s profiteer, the institutionally corrupt NCAA. (Sorry, this week the column has two angry items about fake generosity at the NFL and fake sincerity at the NCAA.)

In most college athletics, the NCAA controls admission standards: Schools, conferences, and the playoff systems regulate themselves. In men’s basketball, the NCAA is purely a profiteer. Most of the NCAA’s revenues come from the roughly $1 billion annually that CBS and Turner Broadcasting pay for rights to the March Madness tournament.

Some analysts believe this money should be distributed to players. Your columnist thinks there should be a much stronger emphasis on actual education, since only a handful of NCAA players ever receive a paycheck from the NBA—the bachelor’s degree, which adds more than a million dollars to lifetime earnings, is the tangible benefit most should receive.

Far too many NCAA men’s basketball players live an illusion of NBA riches and don’t graduate, and colleges don’t care so long as the money flows. Last year 20 percent of players on men’s champion University of North Carolina graduated, a shameful rate even when one-and-done is taken into account. Only 40 percent of Tar Heels women’s basketball players graduated, and leaving early for the pros is barely a factor there.

Whoever’s right in the pay-players or improve-education debate, the NCAA’s role is revolting: intensely concerned with money for the white males who run the NCAA, little concern for education, actively willing to screw over athletes, most of them African Americans, to keep the money in the right people’s pockets. Repeated academic scandals involving men’s basketball at the University of North Carolina resulted in the NCAA doing nothing; the organization’s Indianapolis headquarters just averted its gaze from the most recent preposterous abuse. When college administrators, coaches, and athletic directors know they will never pay any price for cheating, why should they change? But should a men’s basketball player from a major program actually attend class, that must be stopped!

NCAA boss Mark Emmert rivals greedy NFL owners in giving meaning to the expression “unmitigated gall.” He confers on himself $1.9 million a year while denying even minor benefits to the unpaid players who generate his wealth, then delivers self-pitying comments about his own inaction. And he knew nothing, nothing about abuses! At its founding, the NCAA was a reformist organization. Now the NCAA is a corrupt defender of an institutional status quo. Emmert and his cronies are too tainted to be redeemed: Congress needs to put the NCAA out of business.

Plus Oklahoma State Graduated None of its African-American Men’s Basketball Players, and That’s Really Not Because of the Gigantic Number of Oklahoma State Guys Dominating the NBA. Though men’s basketball is the place the NCAA profits via cash and the NBA profits via a free junior league, let’s take a moment to bear in mind that Power Five football is a free AAA league for the NFL: one from which far too many players never receive either an education or advance to a pro paycheck.

For Saturday’s big-deal Oklahoma versus Oklahoma State pairing, Jake Trotter of ESPN reported that Oklahoma State credentialed 25 NFL scouts, including three general managers. Several Oklahoma State players are NFL-bound. Most are not, and in the most recent class, Oklahoma State graduated just 36 percent of its football players, a pathetic result even when the occasional junior-eligible is subtracted.

Maybe Russians Hacked the Donna Brazile Copyedits. Less than a week after publishing a book that claims the Democratic primaries were rigged, Donna Brazile denied they were rigged. This isn’t just a politician trying to have things both ways. Brazile’s claim is a celebrity publishing gimmick: Include scandalous declarations in a manuscript to draw media attention and get the book selling, then have the celebrity make TV appearances denying the claims. The next step, perhaps coming soon, is that Brazile will ask for sympathy by saying she is the victim of a smear campaign, which her own book set in motion.

Perhaps one should place quotation marks around her own “book,” which relies extensively on fake quotes that purport to be exactly what was said, word-for-word, though no one was taking notes. Unless Brazile was wiretapping her phone calls to Bernie Sanders! The “book” is not bound for the Ghostwriters Hall of Fame: “I started to cry, not out of guilt, but out of anger. We would go forward. We had to.” Maybe Brazile is denying the content of her own “book” because she hasn’t gotten around to reading it.

This is separate from whether it would have been okay if the Democrats had in fact rigged their primaries—or if Republicans had rigged their primary to deny Donald Trump the nomination.

One of the structural faults of contemporary American voting is that most states treat primaries exactly as they treat general elections: same polling places, same poll judges. This creates, for voters, the illusion that the Democratic-Republican duopoly is somehow mandated by the Constitution. Political parties are private organizations, not public entities: Why should state governments use public funds to underwrite a primary voting structure that tricks voters into thinking only Democrats or Republicans can be elected?

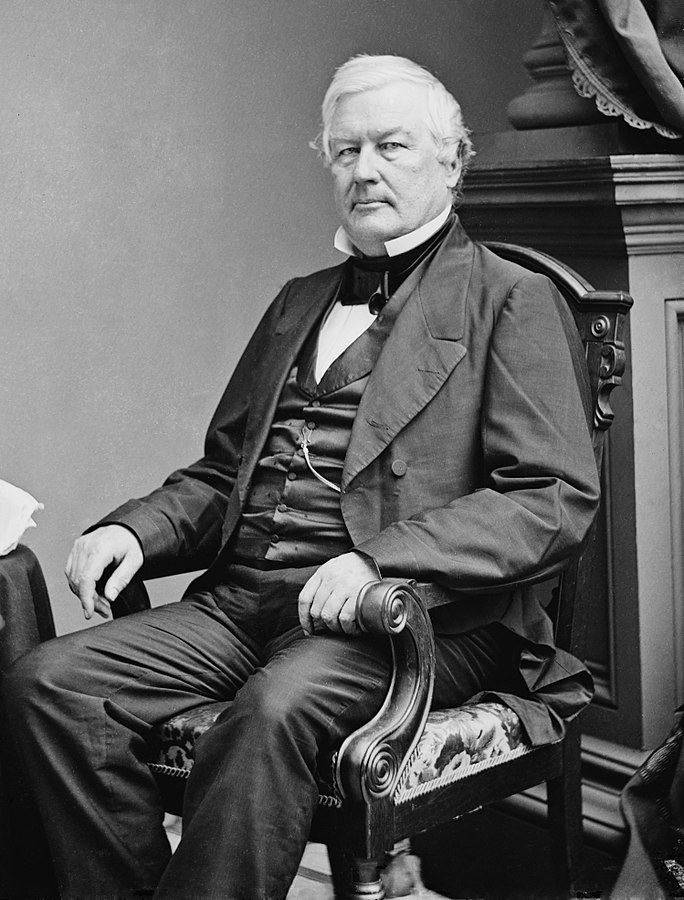

Ending state sanctioning of party primaries might or might not result in better candidates, but at least the duopoly would be undercut. The Framers would be distressed to learn that the most recent president who was not either a Republican or a Democrat was—do you know? Take a little look-see at the year 1850.

The last Whig to be elected POTUS. And not a particularly popular one, the history books show.

Adventures in Officiating. An above item notes the NFL-college rules difference on offensive linemen downfield. In the Atlanta-Carolina contest, the Epic Fails’ Tevin Coleman caught a screen pass behind the line of scrimmage and motored 19 yards for a late fourth-quarter touchdown. Atlanta guard Wes Schweitzer was far downfield before the pass was thrown, which would have been legal in a college game, but should have been flagged in the pros. The no-call was a major mistake by referee Tony Corrente’s crew. Lucky for them the Cats’ 20-17 victory kept this blunder from being noticed by the sportsyak world.

The Football Gods Chortled. After throwing four touchdown passes and no interceptions a week ago in a win over favored Penn State, Ohio State’s J.T. Barrett threw four interceptions in a loss to underdog Iowa. This doesn’t make him weird, rather, makes him normal in a sport where game-by-game performance can vary a lot compared to baseball and basketball.

NFL Games Often Look Bad Because Players Don’t Even Try. Three of the league’s highest paid offensive linemen are Cordy Glenn, Richie Incognito, and Eric Wood of Buffalo: all possessors of extravagant contracts despite none ever appearing in a playoff game. Thursday at Jersey/B, all three were awful, spending down after down barely brushing their men, then standing doing nothing, just watching as Tyrod Taylor was sacked seven times and LeSean McCoy thrice was TFL (“tackled for a loss”).

All three of these underperforming offensive linemen know that for reasons of salary cap amortization and veteran guarantees, no matter how poorly they perform, they will receive the same pay this season whether they play hard or sit down on the field. So they did nothing as their quarterback was sacked and their tailback got hit in the backfield.

This is not just an issue for the Bills, a team with the league’s longest postseason drought. As Miami was being crushed 40-0 at Baltimore earlier this season, several Dolphins offensive linemen stood around doing nothing. On one snap, Miami left tackle Laremy Tunsil, a high first-round draft selection, simply stood watching, not even attempting to make contact with anyone, as five Ravens rushers overcame six Dolphins’ blockers for a sack. Jay Ajayi looked bad in Miami, then instantly looked more talented at Philadelphia, because for Miami he was being hit in the backfield as Dolphins’ offensive linemen did nothing, while with the Eagles, the blockers hustle.

Lethargic line play is an issue for NFL ratings. A generation ago, if the linemen were refusing to try, no one really knew. Today with unlimited replays on TV, smart phones, and tablets, fans know when highly paid NFL guys could not possibly care less, and fans feel disgusted.

Reader Animadversion. Last week I asked readers for absurd wine-snob comments such as “lingering aromas of lead pencil shavings.” Reader Michael Clevette of Middleburg, Florida, notes this description of a red from a wine catalog called Bounty Hunter Wine: redolent of “wet rocks, subtle barbeque smoke, and blueberry pie.” Subtle barbeque smoke! And how does the reviewer know what wet rocks taste like?

The 500 Club. Visiting Louisiana Monroe, Appalachian State gained 508 yards, and lost. As noted by reader Tim Silva of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, visiting Notre Dame, Wake Forest gained 587 yards and lost. Hosting Kansas State, Texas Tech gained 522 yards and lost. In a measure of the scoreboard-spinning college world, Texas Tech is averaging 38 points per game and has a losing record.

The 600 Club. Hosting Slippery Rock, Seton Hill (not Hall) University gained 633 yards on offense, and lost by 39 points. The Seton Hill University Griffins thus joined the Oklahoma State Cowboys is this weekend’s 600 Club.

Obscure College Score. Husson 63, Alfred 0. Division III Husson has won its last four—over Castleton, Gallaudet, Anna Maria and Alfred—by a combined 230-34. Located in Bangor, Maine, Husson University has come of age since its original mission of preparing students for “commerce, teaching and telegraphy.”

Next Week. The NCAA hires Captain Renault to get to the bottom of low graduation rates in revenue sports.