Americans trace the term “populism” to the 1890s, but Russian “populism” (narodnichestvo, from narod, the people) began in the 1870s. The “narodniks” dominated Russian thought for two decades, and their successors, the Socialist Revolutionaries, became the country’s most influential political party until the Bolshevik coup. The importance of Russian populism lies less in its programs than in its ethos, a guilty idealism that can teach us a lot today—not only about populism itself but also about the clash of any idealism with recalcitrant reality.

Russia’s greatest writers, painters, and composers all reflected on, if they did not participate in, what one historian called “the agony of populist art.” “Agony” is the right word to describe a movement whose greatest artists drank themselves to death, committed suicide, or went insane. Russians’ natural extremism makes the problems inherent in all idealistic movements especially visible.

Jolting from one panacea for evil to another, Russian intellectuals at last arrived at worship of “the people,” a term usually meaning the peasants, who constituted the overwhelming majority of the population. Today, the word “populist” is often used as a term of abuse disparaging boorish, mindless followers of a demagogue, but “narodnik,” though originally pejorative, was soon adopted by the populists themselves to indicate their reverence for the Russian people’s innate wisdom. To argue for a policy it was common not to demonstrate its effectiveness but to show that it was supported by “the people,” as if the people could not be wrong. In Anna Karenina, everyone is shocked when Levin, Tolstoy’s hero, rejects this whole way of thinking. “That word ‘people,’” he says, “is so vague.”

Any ideal worth adopting had to explain the meaning of life. In one of his best stories, “On the Road,” Chekhov reflected on such idealism by telling the story of Grigory Likharev, who finds himself snowed in at an inn on Christmas Eve. There he encounters a noblewoman, Madame Ilovaiskaya, on her way to her father and brother, who without her wouldn’t take basic care of themselves. She listens with rapt attention to the charismatic Likharev’s account of his lifelong embrace of one set of beliefs after another.

Likharev always lives “on the road,” journeying from place to place to preach idea after idea. Some people, he explains, possess a talent for faith, a special faculty of the spirit that compels them to believe totally in one thing or another. “This faculty is present in Russians in its highest degree. Russian life presents us with an uninterrupted succession of convictions and aspirations and, if you care to know, it has not yet the faintest notion of lack of faith or skepticism. If a Russian does not believe in God, it means he believes in something else.”

There has never been an hour, Likharev explains, when he did not believe in something. When his mother told him, “Eat! Soup is the great thing in life!” he ate soup 10 times a day “till I was disgusted and stupefied.” When his nurse scared him with stories about goblins, he left poisoned cakes for them. To achieve Christian martyrdom he hired other boys to torture him. Whatever the faith, he always inspired someone else to join him.

At the university, he “gave [himself] up to science, heart and soul, passionately, as to the woman one loves.” He went around preaching the truth that white light really consists of seven colors, and “glowed with hatred for anyone who saw in white light nothing but white light.” He made an ideal of nihilism and accepted materialism for spiritual reasons. At last he arrived at populism, which fit his personality perfectly.

The populists preached “going to the people,” abandoning corrupt cities to live among the peasants in order to educate them and absorb their inarticulate wisdom. “I ‘went to the people,’ worked in factories, worked as an oiler, as a barge hauler,” Likharev explains. “I loved the Russian people with poignant intensity; I loved their God and believed in Him, and in their language, their creative genius. . . . My enthusiasm was endless!”

Likharev worked as a “barge hauler” because that horrible occupation became the populist symbol of the people’s suffering. The most famous painting of the 19th century, Ilya Repin’s heartrending Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-73), depicts a group of men harnessed together to haul riverboats. In a widely read article on contemporary Russian painting, “Apropos of the Exhibition,” Dostoyevsky explains that he anticipated a depiction of barge haulers wearing ideological “uniforms” with “the usual labels stuck to their foreheads,” but to his delight found nothing of the kind. To be sure, he opined, rags like the ones these workers wear would immediately fall off, and one of the shirts “must have accidentally fallen into a bowl where meat was being chopped for cutlets.” But the people are real. Two are almost laughing, a little soldier is concealing his attempt to fill his pipe, and none is thinking about oppression. You love these defenseless creatures, Dostoyevsky explains, and can’t help thinking that you are indeed indebted to “the people.”

Populism fed on guilt, and everything about Likharev, down to his very gestures, expressed a consciousness of guilt about something. The populist ideologists insisted that all high culture depends on wealth stolen from the common people and is therefore tainted by a sort of original sin. As Russia’s greatest autobiographer Alexander Herzen lamented, “All our education, our literary and scientific development, our love of beauty, our occupations, presuppose an environment constantly swept and tended by others . . . somebody’s labor is essential in order to provide us with the leisure necessary for our mental development.” Shame and guilt over unearned privilege shaped a generation of the “repentant nobleman.” Pyotr Lavrov’s Historical Letters (1868-69), the populist bible, put it this way: “Mankind has paid dearly so that a few thinkers sitting in their studies could discuss its progress.”

Perhaps high culture should be abolished altogether? This urgent question came to be called “the justification of culture,” with many writers contending that justification was impossible. Since the symbol of Russian culture was Pushkin, critics, most notably the nihilist Dmitri Pisarev, insisted that any pair of boots is worth more than all of Pushkin’s verse. The nihilists at least worshiped science—like Bazarov in Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, who dissects a frog to show that people are nothing but complex amphibians—but the populists rejected science as well. A story about the writer Vsevolod Garshin as a boy tells how he too dissected a frog, only to take pity on it, sew it up, and let it go. Not knowledge but pity became the moral touchstone. The populist argument about “the justification of culture” became part of what philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev called “the Russian Idea” and, so far as I know, marks Russian culture as unique. (To be sure, it is common today to convict the Western tradition as the product of imperialism and dead white males, but that is still different from rejecting high culture per se.)

If populism fit Likharev’s guilty conscience so well, why did he give it up? Out of guilt, of course. Having run through his fortune and his wife’s, and impoverished their children, he grasped a truth dear to skeptical Chekhov’s heart. Ideologies of all sorts undervalue real people of the present moment and, in pursuit of some superhuman goals, neglect the everyday processes that truly make a life good or bad. “I have lived,” Likharev explains, “but in my fever I have not even been conscious of the process of life itself. Would you believe it, I don’t remember a single spring, I never noticed how my wife loved me, how my children were born. . . . I have been a misfortune to all who have loved me. . . . I cannot even boast, Madam, that I have no one’s life upon my conscience, for my wife died before my eyes, worn out by my reckless activity.”

On the verge of recognizing the harm that ideology does, Likharev converts this insight into yet another ideology. Moved by his wife’s death, he, like other Russian idealists, switches from worshiping peasants to worshiping women and their amazing capacity to sacrifice themselves. More than once, he explains, women have followed his enthusiasms “without criticism, without question, and done anything I chose: I have turned a nun into a nihilist, who, as I heard afterwards, shot a gendarme.” What matters is not what women sacrifice themselves for, but their “wonderful mercifulness, forgiveness of everything. . . . The meaning of life lies in just that unrepining martyrdom.” Russians came to idolize prostitutes and women terrorists as paragons of virtue.

Likharev’s speech mesmerizes Madame Ilovaiskaya. Ever unappreciated, she is amazed that women like herself are his new enthusiasm “or, as he said himself, his new faith!” She is ready to follow him. “With his gesticulations, with his flashing eyes, he seemed to her mad, frantic, but there was a feeling of such beauty in the fire of his eyes, in his words, in all the movements of his huge body, that without noticing what she was doing she stood facing him as though rooted to the spot, and gazed into his face with delight.” He sees this, but leaves without her, and the story ends with his coach disappearing into the storm while “his eyes kept seeking something in the clouds of snow.” Chekhov saw the populist mentality as emblematic of all Russian idealisms—disdainful of everyday experience and, however harmful, immune to any disconfirmation.

Populism’s two best writers both resembled Likharev. Gleb Uspensky (1843-1902) belonged to the movement heart and soul, while Vsevolod Garshin (1855-1888), whom Chekhov especially admired, remained on its outskirts. Known as a “Hamlet of the heart,” unable to commit himself unreservedly to anything, Garshin could describe the populist ethos sympathetically from within and skeptically from without in the same stories.

Uspensky’s personality was made for the populist ethos. From childhood he suffered from paralyzing guilt. If anxiety is fear seeking an object, we lack a word for guilt seeking something to repent for. Even as a child, Uspensky recalled, “I was guilty before the saints, the images, the chandeliers.” One of his heroes claims his generation lives “in the conscience-stricken epoch of Russian life. . . . It was time for society to remember that there is something called conscience.” And it must do so with single-minded urgency: “Right away, at this very minute, one had to work, serve in this giant infirmary and by every means help in bringing health, in curing the sick, the cripples, the monsters.”

The heroes of Uspensky’s sketches, who keenly sense their “swinishness,” seem to care more about easing their souls than helping the people. Such idealism, as Dostoyevsky noted, is really a form of selfishness. The oppressed exist to be saved. Anyone who thinks this way is “An Incurable,” the title of one Uspensky story in which a deacon begs a doctor who has treated his bodily pains for something to cure his soul. The deacon has encountered a wealthy populist woman who has sacrificed everything to “go to the people,” an act of selflessness that makes the deacon’s life meaningless by comparison. The deacon’s spiritual torment, we learn, leads him not to a better life but to abandon his family for drink.

These sketches record Uspensky’s own experience of repeated disappointment. For the populists, the peasant was not just natural man but, even better, natural Russian man, unsurpassed in virtue. Unlike their foreign counterparts, Russian peasants still lived in communes, where people thought more of the group than of themselves. That was the theory, but Uspensky found reality more and more at odds with ideology. Most of his sketches describe an intellectual like himself who first discovers that the peasants are utterly corrupt and then tries to preserve his faith in them with one rationalization or another, as Uspensky himself did.

In one sketch, the narrator realizes that what the peasants most admire is success in pursuit of money. A village hero, Mikhail Petrovich, has accumulated capital by first selling his wife to travelers and then cheating an officer out of his property. Far from disapproving, the peasants elect him their elder, a position he uses to embezzle communal funds, which only makes the peasants he robs admire him even more. “The whole village knew that his wife was consorting with the devil, but the very ability, the knowledge of how to go about it, how to turn things to one’s own advantage—this conquered everyone.”

In another sketch, the narrator discovers that the commune is perfectly willing to let a widow and her child starve. When a neighboring landlord offers to sell the commune land on advantageous terms, the peasants cannot agree because each justly suspects the others of cheating. They brutally beat one of their members to death. Uspensky had once attributed peasant lapses to poverty, but came in time to recognize that the problem was not economic but moral. The populists in Petersburg accused Uspensky of blasphemy.

Uspensky did everything he could to justify the people. In his sketches about the peasant Ivan Ermolaevich, who professes complete selfishness in his pursuit of money, the narrator, at first appalled by his cruelty, eventually decides that Ivan Ermolaevich must be regarded as an artist devoted to his craft. He is, in any case, following “the course of life that is predetermined” for him. “No, he is not guilty. I, the educated Russian, I am most decidedly guilty.” As the historian Richard Wortman observes: “Unable to reconcile the real with the ideal, he idealized reality.”

Uspensky gradually lost his grip on reality. “‘The eternal life’ of the countryside has . . . aggravated and undone my nerves,” he remarked. Haunted by hallucinations, he spent his last years in an asylum. With unrelieved guilt for his “swinishness,” Uspensky came to believe he really was a pig and tried to turn his face into a snout.

Garshin, too, experienced mental breakdowns, moved in and out of asylums, and eventually committed suicide by throwing himself down the stairs. When war broke out with Turkey, he, like a number of others, joined the Russian Army as a private in order to be “with the people.” His story about that experience, “Reminiscences of Private Ivanov,” impressed readers as subtle, understated, and untendentious. If Uspensky’s overriding emotion was guilt, Garshin’s was extreme sensitivity to others’ pain. “This martyr of the spirit,” one contemporary maintained, “suffered from an illness from which it is morally wrong to recover.” His pathological empathy led him to see actual human experience as repulsive, and one of his trademarks was realist descriptions evoking sheer disgust.

His first famous story, “Four Days,” describes a Russian soldier who, like Garshin himself, enlisted without considering he might hurt someone. “The idea that I too would kill people somehow escaped me. I only saw myself as exposing my breast to the bullets.” In the confusion of battle, the hero bayonets a Turk and then, severely wounded, is left for dead next to the Turk’s corpse. He spends four days witnessing and smelling the decomposition of the Turk’s body, which he describes in excruciating detail. “Once when I opened my eyes to look at him, I was appalled. His face was gone. It had slid off the bones,” one such description begins. Usually read as an antiwar tale, “Four Days” may also be taken as a story about the nauseating human condition and the ultimate fate of us all.

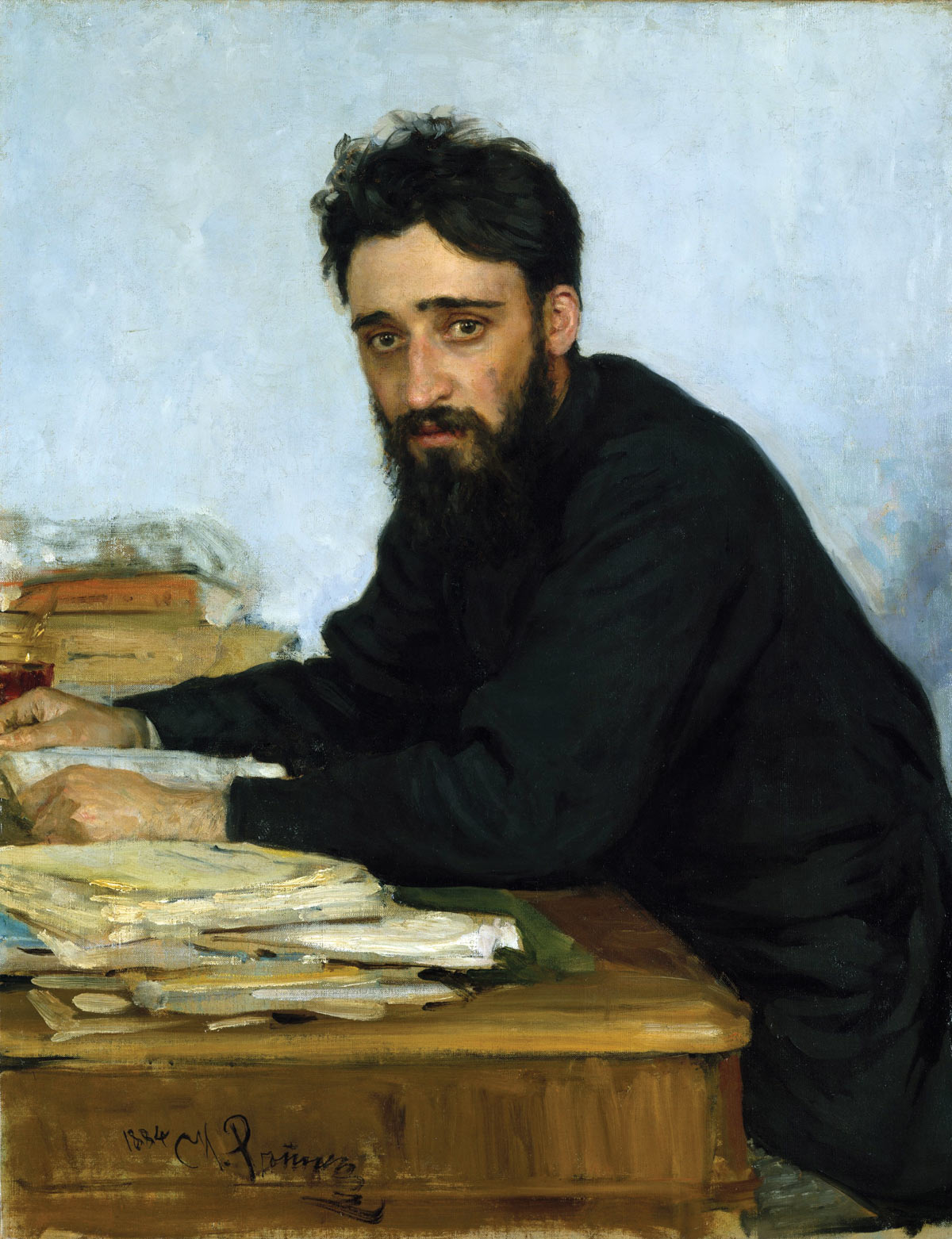

Garshin befriended the Russian painters called “Itinerants,” who favored scenes of Russian life, including pictures of suffering like Repin’s Barge Haulers. Like so many others, Repin was struck by Garshin’s distinctive personal beauty—some said he could be a model for the Savior—and, in his famous painting of Tsar Ivan the Terrible right after he has murdered his son in a rage, Repin gave the dead tsarevich Garshin’s face. His portrait of Garshin shows a man afflicted with a deep, almost metaphysical sadness, at his writing desk. Garshin wrote one of his finest stories about the Itinerants.

“Artists” traces the thoughts of two painters with opposite ideas about art. The kindly Dedov views art’s goal as beauty that moves “a man’s soul to a mood of gentle tranquil wistfulness.” His friend Ryabinin, a populist based on the Itinerants, chooses to paint a worker whose job is to press his chest against a rivet on the inside of a boiler while another workman hammers it. These human anvils represent all the suffering that people inflict on each other. Dedov disparages such work as “looking for the poetic in the mud! . . . All this peasant trend in art, in my opinion, is sheer ugliness. Who wants those notorious ‘Volga Bargemen’ of Repin’s?” Ryabinin, by contrast, paints a canvas supposed to shout to wealthy viewers: “I am a festering sore! Smite their hearts, give them no sleep. . . . Kill their peace of mind, as thou hast killed mine.”

The closer Ryabinin’s painting comes to completion, the more it drains him of health until at last he gives up painting to become a teacher for peasants. As the story closes, the narrator tells us that Ryabinin failed at that profession as well. For all our sympathy for Ryabinin, we wonder whether empathy taken too far does more harm than good. Could it even be a form of self-indulgence?

Some Garshin stories describe a prostitute, Nadezhda Nikolaevna, whom one hero regards the way Chekhov’s Likharev might: as a martyr taking on all human suffering. “An Incident” deals with a man who regards her as a superior being and wants to rescue her. Psychology defeats the dream. A truly Dostoyevskian figure, Nadezhda would rather hold on to her resentment than join the world that looks down on her. You cannot save someone like that, and the hero commits suicide. In “Nadezhda Nikolaevna,” she becomes the model for an artist’s painting of Charlotte Corday, “the fanatic champion of good,” who murdered Marat out of high principle. The painting asks whether violence is ever morally permitted, even to save sufferers like Nadezhda herself. As it happens, another painter wants to depict a legend about how Russia’s great folk hero Ilya Muromets reads the New Testament and discovers that all his glorious military deeds violate Christ’s commands. Am I supposed to let evil happen without resisting it? Ilya asks. “Leave them to plunder and kill? Nay, Lord I cannot obey Thee. . . . I understand not Thy wisdom; Thou hast given my soul a voice, and I listen to that and not to Thee!” The story’s two paintings pose the same question about violence in pursuit of justice. Together, they suggest that art’s goal is to pose, not answer, great questions. As the second painter explains, “You make people think, that’s all. . . . Is it not that which gives meaning to what you are doing?” All Garshin’s stories end with questions.

Garshin’s two best-known tales take the form of parables about idealism. In “Attalea Princeps”—the title is the scientific name of a Brazilian tree—a tree in a greenhouse yearns for freedom. Directing all her energies to growing taller, she plans to break the greenhouse glass and experience the world outside. Eventually she succeeds, but this is Russia and so the Brazilian tree realizes she will die. “Is this all?” she asks herself. “Is this all I languished and suffered for so much?” Ideals fail not only when unattainable but, still worse, when attained, as every revolution shows.

Drawing on Garshin’s own sad experience, “The Scarlet Flower” depicts an idealist in an asylum who knows he is mad and yet believes his insane reasoning. He imagines that he is called upon “to fulfill a task which he vaguely envisaged as a gigantic enterprise aimed at destroying the evil in the world.” All evil, he decides, proceeds from three red flowers growing in the prison yard. One by one, he contrives to pick them, each time holding it to his breast all night to defeat its evil by absorbing it into himself. He wakes up weaker and thinner. Having picked the third flower, he dies convinced that he has rid the world of evil. By morning “his face was calm and serene; the emaciated features . . . expressed a kind of proud elation. . . . They tried to unclench his hand to take the crimson flower out. But his hand had stiffened in death, and he carried his trophy away with him to the grave.” Garshin knew that his own utopianism was futile at best.

Chekhov’s story “A Nervous Breakdown” appeared in a volume dedicated to the memory of Garshin. Like Garshin, its hero, a talented law student named Vasilev,

Vasilev reluctantly accompanies two friends, an artist and a medical student, on a sort of pub crawl from one bordello to another, sampling the awful music, inspecting the intentionally ugly decoration, and talking with the prostitutes. Vasilev has always accepted a sentimental picture of prostitutes as “acknowledg[ing] their sin and hop[ing] for salvation.” Like a populist going to the people, he finds they do nothing of the sort. He discovers no “guilty smile,” as he expected, but finds “on every face nothing but a blank expression of everyday vulgar boredom and complacency.” Tormented by the thought that he “hated these women and felt nothing but repulsion toward them,” he blames himself for seeing them only as animals, as not human.

But he soon sees them as still more repellent: The women do not just lack humanity, they display a sort of inverse humanity, exhibiting the opposite of the best human qualities. “Everything that is called human dignity, personal rights, the Divine image and semblance, were defiled to their very foundations.” Vasilev demands that his friends justify the existence of high culture, of their medicine and art, in the face of such dehumanization. Pointing to Vasilev’s own expression of hatred and repulsion, the artist replies that “there’s more vice in your expression than in the whole street!” Can too much concern make the world worse?

Vasilev descends into near madness: Terror grips him until a sense of repulsion from everything, even noble deeds, leaves him utterly incapacitated. Fortunately, Vasilev’s friends return, he begs them to save him from suicide, and they tend him until the mood passes. Was it only chance that no one saved Garshin? Or is the idealist spiritual condition destined for catastrophe?

The populists’ efforts to “go to the people” failed utterly. Far from embracing their revolutionary ideology, the peasants turned their worshipers in to the police. In despair, many populists—but not Garshin or Uspensky—established the Russian terrorist movement. If Russian history demonstrates anything, it is that nothing causes more evil than the attempt to abolish it altogether. The scarlet flower blooms in the Gulag.

To this day the idea persists that the Russian people, especially the simple rural ones, somehow carry the moral solution to all the world’s ills. Under what Dostoyevsky called their “alluvial barbarism” lies the purest spirituality. For Russians, faith in the people’s virtue is equaled only by another belief: in the moral glory of Russian literature. That belief is warranted.