In the past two decades schadenfreude, a German word that means (according to the Oxford English Dictionary) “malicious enjoyment of the misfortunes of others,” has gained popularity in the English-speaking world. Google’s graph for word usage shows a steep upward curve for schadenfreude during the first decade of the 21st century.

Many observers think schadenfreude is closely connected to envy. In a cartoon by Roz Chast there is this sentence: “Schadenfreude: when simple envy isn’t enough.” Some people may enjoy the misfortunes of people they envy, but one is more likely to have schadenfreude upon learning about the misfortune of a person one dislikes. (Of course we may dislike the person we envy.) We take pleasure in seeing people we dislike get their comeuppance.

A case in point: A few months after I was a fired by a boss whom I disliked, I learned that he had been fired. Schadenfreude! I felt the same way when I read a negative review of a book by a French professor I disliked. He had humiliated me in class by asking me to pronounce the word riche five times. I could not correctly pronounce the French “r.”

The popularity of schadenfreude in English is a relatively recent phenomenon. In When Bad Things Happen to Other People, published in 2000, John Portmann writes: Schadenfreude “has not caught on in America.” Since then, it has. In the award-winning musical Avenue Q, first performed in March 2003, there is a song about enjoying schadenfreude. In April 2018 a writer in the Washington Post said many Americans relished “a golden moment of schadenfreude” when they learned about a video-tape that allegedly revealed what President Trump did in a Moscow hotel room in 2013.

Schadenfreude has caught on in Britain as well. In Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune (2018) Tiffany Watt Smith, a British writer, says we are living in the Age of Schadenfreude. She notes that before 2000, “barely any academic articles were published with the word Schadenfreude in the title. Now, even the most cursory search throws up hundreds, from neuroscience to philosophy to management studies.”

The idea that one should be ashamed by the emotion has receded as the popularity of the term has grown. In a column last month, George F. Will wrote: “In the hierarchy of pleasures, schadenfreude ranks second only to dry martinis at dusk.” And Portmann maintains that “there is such a thing as Good Schadenfreude.”

The 19-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer would be disturbed by the notion of good schadenfreude. He called it “the worst trait in human nature . . . closely akin to cruelty.” Schopenhauer distinguished between envy and schadenfreude. “To feel envy is human; but to indulge in such malicious joy is fiendish and diabolical. There is no more infallible sign of a thoroughly bad heart and profound moral worthlessness than an inclination to a sheer and undisguised malignant joy of this kind. The man in whom this trait is observed should be forever shunned.”

Most contemporary observers would disagree. In The Joy of Pain: Schadenfreude and the Dark Side of Human Nature (2013) Richard H. Smith argues that schadenfreude should not be demonized. The emotion, he says, appears “more in gray hues rather than in darkest black.” Nevertheless, Smith finds schadenfreude troubling; it has “a perverse feel to it . . . because it is a feeling promoted by another’s suffering.” Bill Vallicella, an ex-professor who blogs as “the maverick philosopher,” agrees: “There is something fiendish in feeling positive glee at another’s misery.” Watt Smith, for her part, calls schadenfreude an “utterly shabby” emotion, yet she clearly enjoys it at times.

But was Schopenhauer right? Should we all be ashamed of ourselves? Before answering that question, we need to clarify what schadenfreude is. This is not easy to do.

According to many observers, the 17th-century French aphorist La Rochefoucauld is describing schadenfreude when he says: “We have enough strength to bear the misfortunes of other people.” But La Rochefoucauld is not saying that we take pleasure in the misfortunes of others. He is saying we can endure the misfortunes of others because they are not our misfortunes.

There is a passage from Lucretius’s On the Nature of Things that many observers regard as an early example of schadenfreude: “How sweet is to watch from dry land” a ship in danger of sinking because of stormy weather. “The sweetness,” Lucretius explains, “lies in watching evils you are free from.” The “sweetness” is relief, though, not schadenfreude. The person on the shore isn’t enjoying the doom of those on the ship; he is feeling fortunate that he is not on the ship.

Schadenfreude is always about someone you know—or know about. It would be sadistic to enjoy the misfortunes of anonymous people. But what if the person on the shore knew that the ship was filled with marauders who had raped and pillaged his village? Then he is likely to feel schadenfreude. The Bible says: “Do not rejoice when your enemies fall; and do not let your heart be glad when they stumble” (Proverbs 24:17). But most human beings rejoice when their enemy falls.

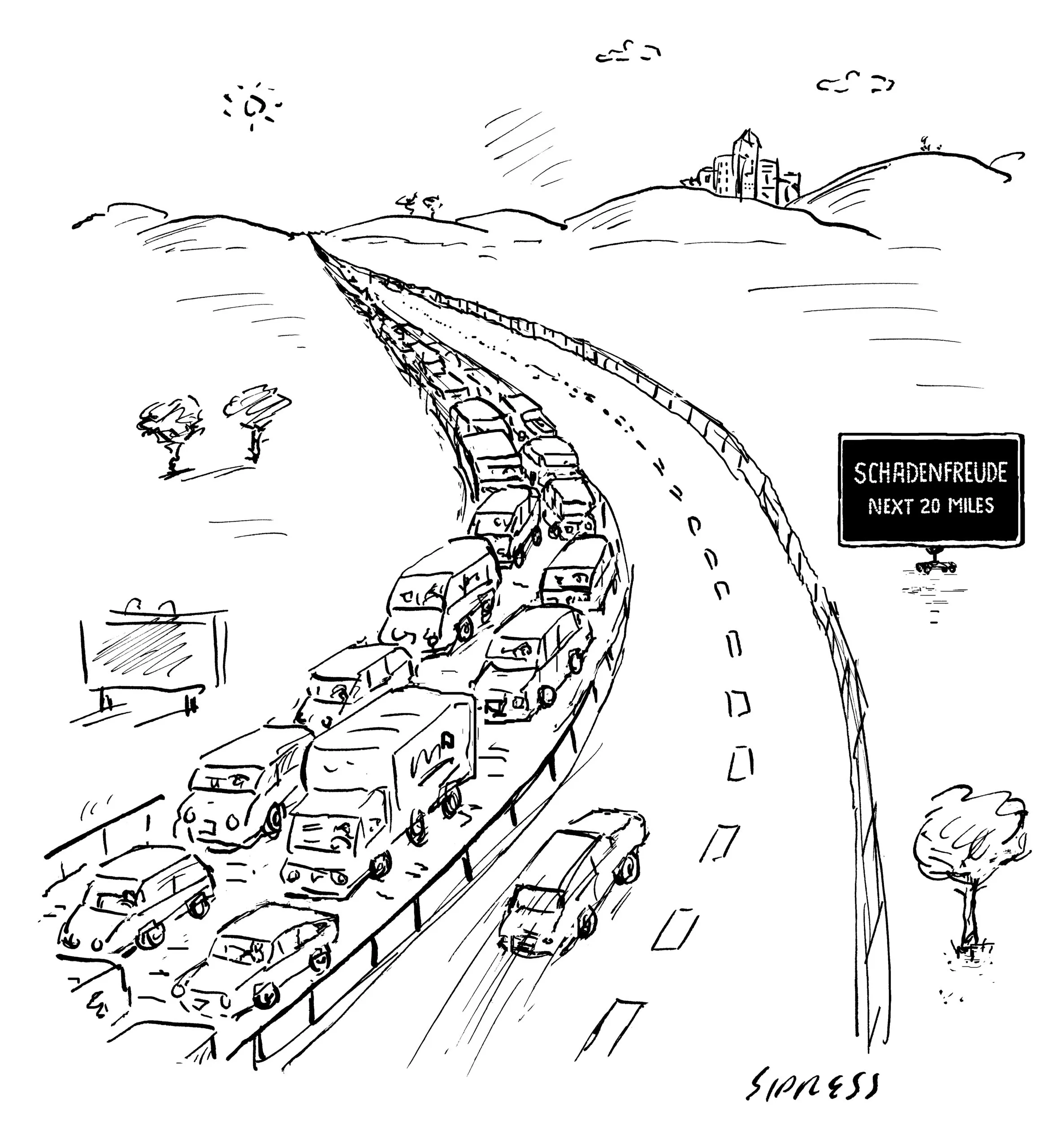

One more example of a misuse of the concept. A New Yorker cartoon shows a massive traffic jam on one side of a highway, but on the other side the traffic is moving smoothly. On the traffic-free side there is a large sign that says, “Schadenfreude Next 20 Miles.” The cartoon implies that those driving on the traffic-free side take pleasure in the misfortune of the drivers stuck in traffic, but surely the main emotion is thankfulness that they are not in a similar jam. They might feel vaguely sorry for those stuck in traffic but they do not feel schadenfreude.

But what if I were driving on the traffic-free side and knew there was someone stuck on the other side whom I intensely disliked? The pleasant thought of him stewing there, cursing his bad luck—that is schadenfreude.

Most often, probably, the feeling arises about people in the news. Many people felt schadenfreude when they learned that Martha Stewart was accused of insider trading. Michael Kinsley called her trial and eventual incarceration “a landmark in the history of schadenfreude.” Joseph Epstein says he felt “a fluttering of not very intense but still quite real Schadenfreude of my own at her fall.” Richard H. Smith says that many people felt this way about Martha Stewart’s arrest because they envied her, but I doubt that Michael Kinsley or Joseph Epstein envied Martha Stewart.

The trigger, instead, is learning that someone who has made much of his or her superiority—moral, intellectual, financial—is not so superior. Stewart had promoted herself as a flawless hostess, so many people gloated: “Martha Stewart screwed up!” Schadenfreude is usually fleeting. The same people who felt schadenfreude about Stewart’s prison sentence may also have admired her for taking the sentence in stride and resuming her career afterwards.

Do we feel schadenfreude when any eminent person suffers a misfortune? In Mao’s Last Revolution, Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals speculate that when Mao urged the masses to denounce high Communist party officials during the Cultural Revolution, “he may have counted on the Schadenfreude of millions of his countrymen at the fall of the high and the mighty.”

I doubt that most Americans reflexively experience schadenfreude at the fall of a high and mighty politician. They would first have to dislike this person. I would not feel schadenfreude if I learned that Ronald Reagan had taken bribes; I would be deeply disappointed because I admired him. But if I learned that Jimmy Carter, who struck me as sanctimonious, had a mistress I would feel schadenfreude. Millions, of course, would experience schadenfreude if they learned that Donald Trump had lost a lot of money in hotel and golf course deals.

Ron Chernow notes that Alexander Hamilton felt schadenfreude when he learned that Horatio Gates, a general he despised, had fled from the scene of battle. “Was there ever an instance of a general running away, as Gates has done, from his whole army?” Hamilton wrote. If Hamilton had admired Gates, he would have been upset.

A literary example is the pleasure we feel at the end of Molière’s Tartuffe, when the eponymous scoundrel is sent off to jail. Tartuffe uses religious piety to gull the head of a family into signing over his house to him and disinheriting the son, so it is reasonable to take pleasure in Tartuffe’s arrest. In comedies there is always pleasure when the bad guy gets what he deserves, but in tragedies the main emotion we feel when an evil person dies is catharsis—a kind of deep relief that order is being restored. In real life when evil people are brought to justice, we feel catharsis and relief—and maybe the pleasure of revenge.

Intellectual life is a great breeding ground for schadenfreude. I am pleased when I learn that a writer I dislike has gotten a bad review or that his novel is not selling well. Is this because I envy the writer? Not necessarily. I don’t envy the literary critic Edmund Wilson, but I dislike him, mainly because of his political views; he admired Lenin and thought the Cold War was the fault of the United States. I felt schadenfreude when my Hungarian wife pointed out that every Hungarian word or phrase that Wilson used in an article he wrote about learning Hungarian was grammatically incorrect. I felt schadenfreude when I read Patricia Blake’s comment about Wilson’s proficiency in Russian: “It would seem that this most erudite man’s great weakness was that he loved to display linguistic expertise he scarcely possessed.”

Wilson accused Vladimir Nabokov, a friend who became an ex-friend, of schadenfreude. In Upstate: Records and Recollections of Northern New York, Wilson writes: “The element in his work that I find repellent is his addiction to Schadenfreude. Everybody is always being humiliated.” In A Window on Russia, published posthumously, Wilson makes the same point more strongly, saying that “the addiction to Schadenfreude . . . pervades all his work.” This is nonsense. Anyone who has read The Gift, Pnin, and—especially—Speak, Memory knows that Nabokov often writes affectionately and movingly about people. But he writes sarcastically about people whom he regards as fools. He did not take kindly to being lectured to by Wilson about Russian history and the Russian language.

What are the limits of schadenfreude? Richard H. Smith’s book on the subject is called The Joy of Pain, but schadenfreude is rarely about enjoying someone’s pain; it is usually about enjoying the fall in a person’s reputation.

Is it right to feel schadenfreude if we learn that someone we dislike is suffering from a life-threatening disease? Joseph Epstein nicely states the problem: “I recall learning of cancer having been found in a literary critic who always claimed something close to moral perfection for himself. I recalling telling this to my wife, adding that, moral prig though I thought him, I didn’t wish him to die.”

In general we don’t feel schadenfreude if the misfortune is catastrophic. If I learned that the boss who fired me died of cancer, I wouldn’t feel schadenfreude. I would feel nothing at all. But I might feel something akin to schadenfreude if I learned that a dictator who had imprisoned and murdered millions was suffering from a painful and fatal disease. John Portmann writes that “Schadenfreude can accommodate great suffering because the notion of desert that lies at the heart of much Schadenfreude can expand infinitely.”

We usually experience schadenfreude from the misfortunes of jerks, not despots. Another of Roz Chast’s New Yorker cartoons, entitled Adult Amusement Park, depicts what I would call schadenfreude. One of the park’s attractions: “Be filled with glee as supermarket-line-cutter-inner gets parking ticket!” I feel schadenfreude when someone who has been driving like a maniac gets pulled over by a cop. I feel it when someone in a restaurant who has been giving a waiter a hard time accidentally gets something spilled on him. I get many scam phone calls—four or five a day—so I would feel a great rush of schadenfreude if I learned that someone who made a living doing this was convicted of fraud.

What about sports and schadenfreude? A website called Words in a Sentence offers this example: “When the winning team saw their rivals saddened by defeat, they felt a sense of schadenfreude.” I doubt this is the feeling of many winning teams. To feel that way is unsportsmanlike. But what if the losing team had engaged in trash talk—bragged that they were the superior team and would win easily? Then schadenfreude on the part of the winning team would be appropriate.

Is taking pleasure in watching people on reality TV shows make fools of themselves a type of schadenfreude? Richard H. Smith devotes an entire chapter to “humilitainment.” One could say that these people have chosen to act like fools, so taking pleasure in their humiliation is legitimate. But we do not know these people and have nothing against them. “Humilitainment” is a creepy and distasteful kind of schadenfreude.

There is an even uglier kind of schadenfreude—the malicious pleasure someone gets from the misfortune of a friend. La Rochefoucauld writes: “In the adversity of our best friends, we always find something that does not displease us.” He may only mean that we are relieved that it is not our misfortune. In any case, this maxim did not appear in the second edition of the Maxims, so maybe La Rochefoucauld was no longer happy with it.

Nevertheless, the maxim stirs up a question: Do I experience schadenfreude if a book written by a friend gets a bad review? Gore Vidal said: “Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.” If my friend is a more successful writer than I am, wouldn’t I enjoy learning that one of his books is a failure? Edmund Wilson, one critic says, wrote a very negative review of Nabokov’s translation of Eugene Onegin because he was envious of Nabokov’s success. Wilson’s novel, Memoirs of Hecate County, was not well-reviewed and did not sell well; Nabokov’s Lolita, which came out a few years later, got good reviews and made Nabokov rich and world-famous.

Writers are very competitive souls. Samuel Johnson wrote, “The reciprocal civility of authors is one of the most risible scenes in the farce of life.” I have one friend who is a very successful writer; I envy her but in a benign way. I don’t think I would experience schadenfreude if her next book were a failure. But maybe I’m so ashamed of the idea of enjoying a friend’s failure that I won’t admit it to myself. La Rochefoucauld says: “It is as easy to deceive ourselves without noticing it as it is hard to deceive other people without their noticing it.”

Some people are more prone to being envious than others, and therefore they are more likely to feel schadenfreude if the person they envy suffers a misfortune. In Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, Robert M. Sapolsky cites a recent study that shows a neurological correlation between the pain of envy and the pleasure of schadenfreude. “More activation of pain pathways at the news of the person’s good fortune predicted more dopaminergic activation after learning of their misfortune. Thus there’s dopaminergic activation during schadenfreude—gloating over an envied person’s fall from grace.”

A Princeton study reports similar results, but the researchers noted that many of the people whose brains’ pleasure centers lit up, so to speak, at an envied person’s misfortune did not admit that they felt pleasure. This unwillingness to admit to the feeling is understandable. Our pride—our desire to think well of ourselves—makes us ashamed to feel schadenfreude when a friend we envy suffers a misfortune. La Rochefoucauld offers an explanation: “Often the pride that rouses so much envy also helps us to mitigate it.”

A friend of Tiffany Watt Smith’s confides, after too much to drink, that he is very envious. “The thing that I get, and I mean a lot, is when my friends do better than me. I hate it.” Are most people as consumed with envy as this man seems to be? I doubt it. If someone is always comparing himself to others, he or she is likely to be miserable.

Most people experience a twinge of schadenfreude occasionally. It’s shameful to feel schadenfreude when hearing about the misfortune of a friend, but it’s not shameful to feel schadenfreude when learning about the misfortune of an arrogant self-promoter or a self-righteous blowhard. Richard H. Smith says “the deservingness of a misfortune can go a long way in disconnecting schadenfreude from shame.” Researchers in the Netherlands found that schadenfreude is common when a misfortune is perceived as deserved.

I am sure that even Schopenhauer would have had a rush of schadenfreude upon reading a negative review of a book by Hegel, whom he called a charlatan. Schopenhauer’s biographer says that he “delighted in obtaining any information that he could use to demean the philosopher of the absolute”—i.e., Hegel.

Schadenfreude is here to stay. There are words or expressions for it in many languages besides German, including Danish, Hebrew, Dutch, Chinese, Hungarian, and Russian. And a life without schadenfreude is a life with little or no humor. Anyone who agrees with Schopenhauer’s view of schadenfreude, John Portmann says, “would make a poor comedian.” Schopenhauer indeed seems to have been humorless; he said that nature had endowed his heart “with suspicion, irritability, vehemence, and pride.” His publisher called him “a chained dog.” His mother broke off relations with him because he was so arrogant and ill-tempered.

“Our temperament decides the value of everything brought to us by fortune,” La Rochefoucauld says. A daily dose—a small one—of schadenfreude may improve our temperament, making us better able to cope with our own misfortunes.