How to Behave Badly in Elizabethan England

A Guide for Knaves, Fools, Harlots, Cuckolds, Drunkards, Liars, Thieves, and Braggarts

by Ruth Goodman

Liveright, 314 pp., $28.95

Every reader of Shakespeare knows a few things about Tudor etiquette. We learn from Romeo and Juliet that it is offensive to bite one’s thumb at someone, and from numerous places in the canon that there is a thou/you distinction corresponding to that between tu and vous in French. In this rigidly hierarchical society, minute distinctions of precedence, dress, speech, gesture, and expression assume major importance. They are a means of preserving harmony. “Take but degree away, untune that string,” as Ulysses warns in Troilus and Cressida, “and hark what discord follows.” Ruth Goodman’s entertaining book offers us a cacophony of solecisms: studied insults, contemptuous postures, open subversions of the norm, physical violence, and disgusting habits. She has researched numerous Elizabethan guidebooks to acceptable behavior and gaily turns their prescriptions upside down. Anyone following her advice will be well prepared to be thrown out of practically any social occasion.

Of course, the rules had to be learned before they were broken. To master the correct ceremonial bow was no light matter: How far apart do you keep your feet? What do you do with your knees? Only after extensive practice could you make an inappropriate bow that would really insult the recipient. (It could work the other way, too; Goodman notes that Queen Elizabeth once kept the French ambassador with his head nearly to the floor for 15 minutes as a sign of her displeasure.) There was a bewildering choice of possible ways to walk: the military swagger, the clerical shuffle, the laborer’s plod, not to mention the bizarre gaits of foreigners. To strut where you were supposed to stroll could get you into trouble. Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks would have been much admired in certain Elizabethan circles.

Meanwhile, the strict sumptuary laws, which regulated the dress proper to the various social classes, dictated that ruffs were for courtiers only, hats were for men but caps for women, and green was an immodest color for anyone to wear. To sport the “wrong” attire posed a direct challenge to authority. Goodman devotes some space to Mary Frith, “Moll Cutpurse,” the most celebrated cross-dresser of the period, who figures in the play The Roaring Girl (1611) by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker and even appeared as herself in one performance. She was a scandal in her day but would pass unnoticed in ours.

Foremost among the kinds of bad behavior for which Shakespeare provides a rich source of information is the elaborate insult. Kent’s virtuoso denunciation of the steward Oswald in King Lear is hard to beat; it runs, in part, “a lily-livered, action-taking knave, a whoreson, glass-gazing, super-serviceable finical rogue,” culminating in the magnificent “nothing but the composition of a knave, beggar, coward, pander, and the son and heir of a mongrel bitch.” What makes it worse is that Kent, who as an earl is actually Oswald’s social superior, is disguised as a rough serving-man and therefore apparently beneath him in degree. Kent boasts of his plain speaking; it lands him in the stocks, as it would have done in reality. Goodman tells us that some insults were even decibel-specific; to shout “blockhead” at someone in the street was over the top, since the term was customarily used in private conversation. For public consumption “clown” or “ass” would be better.

Probably the most serious accusation was “liar.” We remember Touchstone in As You Like It, who, having analyzed insults into various categories, ranging from the mild Retort Courteous to the more ominous Countercheck Quarrelsome, goes on to enumerate five other varieties of lie, the last of which, the Lie Direct, is the worst; yet all of these could be avoided by making the accusation hypothetical, with an “if.” “Your if is the only peacemaker,” he concludes, “much virtue in if.” Without an “if,” however, “liar” would automatically prompt a duel, at least among gentlemen—women and those of low social standing could have their veracity questioned with impunity.

Indeed, insults directed against women reached a virulence that would cause a riot in contemporary society. Male honor was bound up with courage, female honor with sexual continence. Thus, a complex register of insults for unchaste women developed, such words as “waggletail,” “quean,” and “trull” implying different kinds of impropriety. The public “flytyng” or slanging-match was a minor spectator sport, like rap battles or Twitter-trolling before their time. Not surprisingly, given the premium placed on one’s reputation, cases of defamation were frequently brought before the courts. Goodman thinks that times have changed, that we judge social standing more by the acquisition of material objects than by deferential behavior. I’m not so sure; social media are a powder keg, and in certain contexts and on certain subjects you have to watch what you say to others more than was the case 20 or 30 years ago.

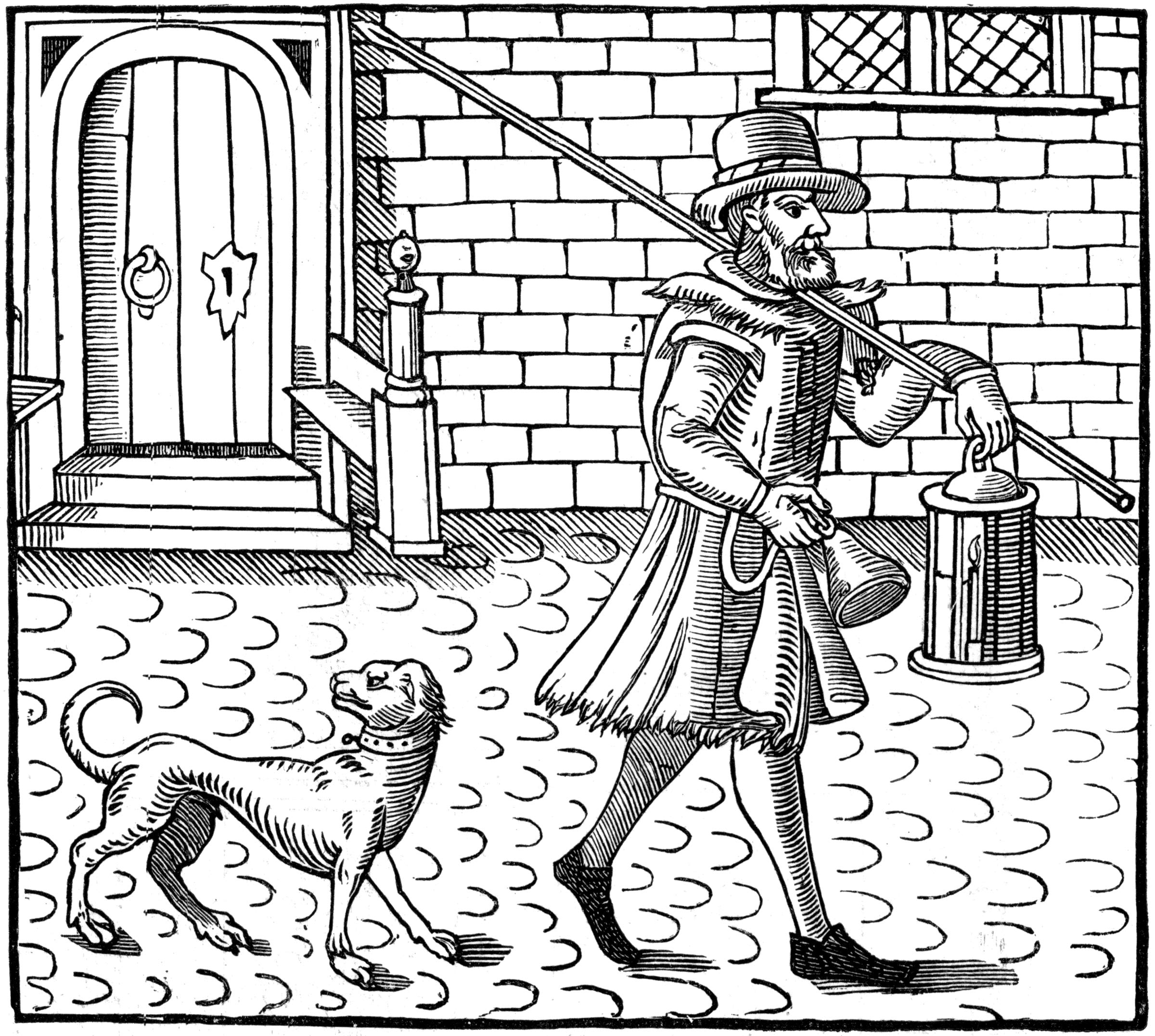

Verbal insult could quickly turn physical. Brawls and assaults—Goodman documents several cases—frequently led to injury or even death. Christopher Marlowe was famously killed after a quarrel over a tavern bill and Ben Jonson was briefly imprisoned for killing a fellow actor in a duel. It was crucial to be adept at the use of weaponry, and here again there were grades of implement for each class: swords for soldiers, courtiers, and gentry; staves or clubs for common citizens. With no standing army or police force, and with a high risk of being attacked by thieves or footpads, it was important to be well armed. Goodman provides a handy explanation of how to fell an opponent with a hardwood staff (shod with iron at the bottom end). As with the other customs described in the book, abuse of the correct procedure was widespread. Some men carried weapons to show off their virility, making menacing passes at the air but too timid to inflict real damage. (So Hotspur, in Henry IV, Part 1, refers scornfully to Prince Hal as “that same sword-and-buckler Prince of Wales.”)

Attendants on the nobility were customarily armed and, in obedience to the sumptuary laws, wore the livery of their masters. This survival of medieval feudalism, Goodman observes, was in decline under the Tudors as power was centralized in the court. Aggression could be channeled into more formal sports such as prizefighting. Henry VIII set up a scheme of instruction in such arts, taught by Masters of Defence, who themselves had to qualify by seven years’ apprenticeship. Bouts were strictly regulated, all-out violence being against the rules. However, as Goodman explains, towards the end of the 16th century these activities were displaced by fencing, an Italian import that became all the rage. Elite fencing schools replaced the academies of the Masters of Defence, and the new sport brought with it new fashions and new body language. None of this put a stop to the “roaring boys” or street gangs, whose sporadic mob violence is invariably condemned in Shakespeare’s plays: Some ways of hurting other people were simply unacceptable.

Goodman’s chapter on “Disgusting Habits” is the most shamelessly enjoyable—and not for the faint-hearted. It is packed with tips, many drawn from Thomas Dekker’s Guls Hornbook (1609), on how to eat badly, how to offend your fellow diners by various bodily emissions, and how to get drunk (not difficult, given that water was—not without reason—thought to be unhealthy). We hear of one epic drinking session in Essex, for which Goodman unfortunately provides no date, that lasted 48 hours. All five senses could be troublesome, according to your inclination; if we were to be transported to Elizabethan England we would probably faint from the smell. The body was ideally a private place, and its exposure in any form was potentially offensive (Falstaff’s unabashed carnality is a positive take on this idea). The medical remedies for bodily ailments were often little better than the ailments themselves. Dr. John Hall, Shakespeare’s son-in-law, recorded his consultations with numerous female patients, and his treatment of choice was purging. Goodman notes our continuing awkwardness about genitalia and bodily functions; arguably we have overcompensated by insisting upon talking about them.

Goodman concludes her survey by observing that “bad” behavior was differently defined as fashions changed and that, even today, we adjust our habits of speech and body language according to circumstances and the company. The young continue to be self-consciously provocative while older generations continue to tut-tut at declining standards. Random violence is, alas, still with us. The differences, though, are obvious. Attitudes toward sexuality have changed with dizzying speed. The whole concept of a hierarchically or divinely ordered universe has receded dramatically. And the Elizabethans, Goodman believes, “valued reputation and respect far, far more strongly than we do.” That is likely to become still more the case in the future, no matter what new ways we find in which to behave badly.