A famous quote about insanity, usually attributed to Albert Einstein — that it can be defined as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” — actually dates to 1980, appearing in different forms in materials published by Narcotics Anonymous.

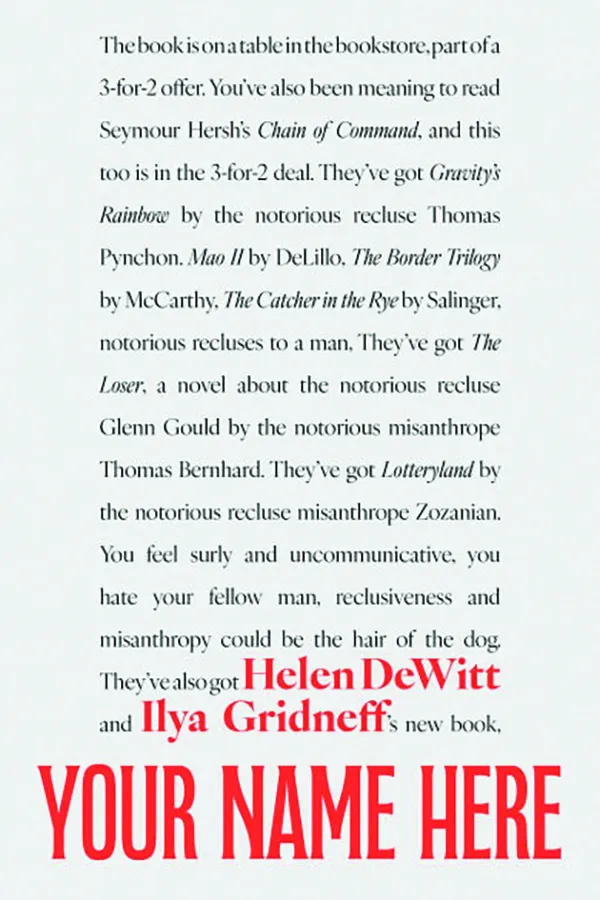

Your Name Here, the long-gestating meta-autofictional epic from cult literary hero Helen DeWitt and journalist and first-time author Ilya Gridneff, evokes that feeling in both its lofty and prosaic origins. Pinwheeling through lengthy direct-address second-person passages, multiple novels within the novel, a series of emails between the two authors, a series of emails between fictionalized versions of the two authors, infographics, Arabic text, and the occasional enigmatic photograph of Marcello Mastroianni, Tom Cruise, or Bob Hoskins and Jessica Rabbit, Your Name Here is a chaotic book-length chronicle of the maddening process of writing and publishing the book itself.

A word of context: DeWitt is the author of, among other books, The Last Samurai, published first in 2000 to glowing reviews, and fêted after its 2016 republication by New Directions Publishing as a modern classic (a Vulture headline declared it “The Best Book of the Century [for Now]“). The praise is warranted: A fiery jeremiad about cultural sloth, ignorance, and oppression disguised as a hyperliterate coming-of-age story, the book is unlike any other, inspiring a passion bordering on evangelism in its devoted fanbase that seemingly grows by the year.

Since then, DeWitt has produced the satirical novel Lightning Rods, published by New Directions in 2011, but written more than a decade prior, and a short story collection and novella, also published by New Directions. Your Name Here was first self-published as a PDF by DeWitt in 2008; n+1 excerpted the first chapter, calling it “an important and complicated work of art which unjustly has not yet been able to find a publisher in the United States or England,” while in the London Review of Books Jenny Turner lauded its complexity as “a novel that doesn’t really believe in novels.” Ultimately, no publisher was willing to take the risk on such a work until DeWitt’s new agent sold it to Dalkey in 2022, as the New York Times reported in a recent profile.

In the realm of the physical, bearing a jacket quote from literary it-girl Lauren Oyler, and comparisons to Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation. (2002) and Italo Calvino’s labyrinthine If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, the book feels like the unwieldy, bespoke object that it is. It is ever so slightly taller than a traditional paperback, clumsy to hold even in your critic’s outstretched, bass guitar-playing hands. There are unpredictable changes in font, font size, font color, the didactic use of Arabic script, and the aforementioned and poorly rendered photographs of tabloid stars. Like Calvino’s story, referenced at length in the text of the book itself, it constantly reminds you that you are reading a book.

To what end? DeWitt’s great fixation as an author is the seeming impossibility of building an intellectual and creative life in a world that pullulates with hostility toward those pursuits. In The Last Samurai, numbskulled London Underground riders look askance with judgment at the mother of the child prodigy protagonist; avaricious, robotically uncreative editors and agents are the villains in much of the rest of her published work. Your Name Here is no different. While the maximum length of this review would not bear an outright recounting of the book’s many overlapping narratives and frames, they are dominated by a struggle for the liberation of the creative voice, not just from opposing commercial-minded forces, but the depression and sloth that accompany the battle with those forces.

Just for fun, let’s briefly try to unpack the book’s facets: There is a series of emails between DeWitt and Gridneff discussing the writing of Your Name Here. There is a series of emails between “Rachel Zozanian,” a thinly fictionalized version of DeWitt, and “A.P. Pechorin” (among other aliases), the double of Gridneff. There are excerpts from Lotteryland, Zozanian’s hit cult novel, and excerpts from Hustlers, a novel about an Oxford student who turns to sex work to pay her tuition. There are second-person passages describing your imagined experience reading Your Name Here. There are first-person passages describing DeWitt’s meetings with Gridneff, or possibly Zozanian’s meetings with Pechorin. There are passages describing Zozanian’s flight from society and suicide attempt, seemingly modeled on DeWitt’s own. I am probably missing a few things.

To the extent that Your Name Here has a narrative engine, it’s the email exchanges between DeWitt/Zozanian and Gridneff/Pechorin. The author develops a giddy obsession with the journalist’s gonzo missives, pushing him onto an agent as “the next Hunter Thompson.” She mentors the journalist from afar, encouraging him to collect as many emails as he can for publication as his own book, and they begin to devise the text that will, decades later, end up in your hands as Your Name Here.

Although one suspects that the two authors would frown on such a criteria (at one point the second-person narrator sympathetically, but with an unmistakable whiff of condescension, addresses a reader who is “extremely aggrieved,” craving a more traditional narrative), the problem with these emails as the driving force behind Your Name Here is that they simply do not inspire anything like the elation and inspiration described by DeWitt. Discursive, vulgar, erratically punctuated, and brainy in a show-offy kind of way, Gridneff’s provocative, hyperkinetic style will be familiar, and often tiresome, to anyone who’s spent the past two decades in the trenches of the blogosphere and internet forums.

REVIEW: THE DECENCY OF EYES WIDE SHUT

Still, befitting a writer of DeWitt’s talent and genius, there are genuine wonders to carry even the story-craving plebeian through the book. The ergodic looney-tunes action is laced with pure, beautiful prose, like her description of rowers on the Thames at Oxford: “Bands of gold spread from the dipping blades. The sky was bracing blue, a gung-ho coach oblivious to cold.” DeWitt’s comic timing is, as always, impeccable (“It’s still snowing in Berlin. It’s still bombing in Baghdad.”) Lotteryland, the novel-within-a-novel apparently adapted or borrowed from another of DeWitt’s many unpublished manuscripts, is a hoot. It’s a satire of the dreary economic hangover from Cool Britannia, pitched somewhere between David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), and it begs for publication or further excerpt. Like in The Last Samurai, the portrayal of depression is serious, plangent, and, clearly, dearly earned.

But ultimately, Your Name Here is about the thrill of the game, the healthful exertion of the life of the mind, more so than its causes, challenges, or second-order effects. In an interview with the Baffler, Gridneff said that while the book “was written with serious intent … there’s only really laughter, or humor, to cope as a sort of rupture” between seriousness and human dignity and the postmodern abyss of digital technology and communications. The extent to which the reader enjoys Your Name Here will depend on their appetite and appreciation for this particular brand of humor and these types of games.

Derek Robertson is a writer in Brooklyn.