Football, an ambitious collection of essays from veteran cultural critic and novelist Chuck Klosterman attempting to capture the sport’s past, present, and future, arrived in stores Jan. 20. This was just in time for introspective pigskin devotees to pick it up during the dreaded, dead week between the NFL’s conference championship games and the Super Bowl, when they must confront the unappetizing binary of either pretending to enjoy a football-adjacent televised event now called the “Pro Bowl Games” or meekly accepting the first agonizing week since August with no football whatsoever.

For those who think this sounds a bit dramatic, Football is, if nothing else, the most thorough exegesis since Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes of how the sport bewitches a man’s mind, body, and soul, becoming something more than a pastime, nearly a coherent philosophy, and just short of a religion. “I know that if someone I like invites me to a book reading on a Friday night in November, I have to attend,” Klosterman writes on the book’s final page. “I can’t say, ‘I’d love to hang out, but Colorado State is playing Wyoming, and both teams are 6-2’ … so I say nothing. I go to the reading and stare straight ahead, wordlessly worrying that it might be blizzarding in Laramie and I’m missing a snow game.”

Klosterman’s thesis for why football so captures the American spirit isn’t completely novel. He argues in so many words that it represents the irreducible remainder of danger, bravado, and risk in human existence, even in the age of biohacking, the FitBit, and “protein popcorn,” and therefore invites our morbid fascination and mythmaking, a memento mori of the tooth-and-claw violence of life on Earth that we’d rather forget.

Its provocative opening chapter puts forward an argument that, while compelling, is ultimately secondary to Klosterman’s trenchant, funny ruminations on the sport: That at some point 50 or 100 years from now, its dominance will be a thing of a past, with our collective social relationship to danger evaporating in the same manner that our social relationship to horses did in the early 20th century (therefore knocking horse racing off its own bygone place atop the sports hierarchy).

Doomy predictions about the future of football date back to the early 20th century, when Theodore Roosevelt threatened to ban the sport after 19 players died during the 1905 college season. Klosterman argues the most likely scenario for football’s demise is that every year fewer and fewer young people will play it, and they will be so concentrated in particular geographic areas that the personal connection between the average person and the sport will diminish to nearly nothing. At this point, a disruption like a strike that results in the cancellation of NFL games will be met by a collective cultural shrug.

He implicitly refutes this idea, however, by establishing what links the sport to deep American-ness: worship of the gallant, unimpeachably moral hero (in a moving chapter about his childhood worship of Dallas Cowboys legend Roger Staubach), the self-obsessed, entrepreneurial obsession with getting some “skin in the game” (in a chapter on videogame football, fantasy football, and sports gambling), and the stubborn insistence on empiricism and results (in a chapter on the godlike archetype of the winning football coach).

As dire as things might sometimes seem, it’s arguably more difficult to imagine those qualities entirely vanishing from American life than it is to imagine the children of Massillon, Ohio, converting en masse to cricket. Klosterman speculates that if coaching titans Bill Belichick and Nick Saban were to read his book, “they would find it facile, inaccurate, and a waste of time. I’d disagree with that analysis, but I can’t lie: Such a reaction would make me respect them more … [coaches] are the last radical pragmatists, detached from any notion of an unfixed universe.”

Of course, given the book’s grand attempt to capture the last bastion of American monoculture — aside from maybe Taylor Swift, who is, naturally, engaged to marry an NFL player — Klosterman must address the sport’s inevitable, high-profile clashes with messy, contested, and unfixed modernity. A chapter on the long, racially fraught history of black quarterbacks ends with the kind of insight about the activist former San Francisco quarterback Colin Kaepernick that’s almost impossible to reach in the shrill heat of controversy: that yes, Kaepernick’s career was already going downhill when he began his protest, but that actually made it far more meaningful than it would have been were he a Tom Brady-level superstar, given the precarity of his place on the roster.

In the same spirit, a chapter about traumatic head injuries to football players dares to state the elusive obvious that Americans of sound mind and body are free to endanger themselves any way they choose, with our willingness to turn that risk into commercial spectacle depending on the obscenity of the violence (i.e., until someone once again dies on the field, as it appeared Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin would in 2023 before his full recovery from what turned out to be a freak medical accident).

Klosterman prefaces this conclusion by recalling a concussion he suffered in his own teenage playing days. It’s told with his trademark ability to flit between TV-fueled Gen-X reverie and brutal, anecdotal clarity: “We collided like bighorn sheep in a commercial for Dodge pickup trucks … I’d like to say we both went down, though that can’t be verified.” Football sits next to The Nineties, his previous book, as both his best work and his most personal. For Klosterman, there is little meaningful difference between the monoculture and our personal lives; the former is constructed and given meaning by the latter. America’s vast, multitudinous individuality and its aching, lonely, never-to-be-fulfilled desire for oneness and transcendence are two sides of the same coin. Football, with its faceless, helmeted gladiators sublimating their raw individual talents to the leadership of a charismatic head coach, is e pluribus unum, a spectacle with real winners, real losers, and the attendant spoils.

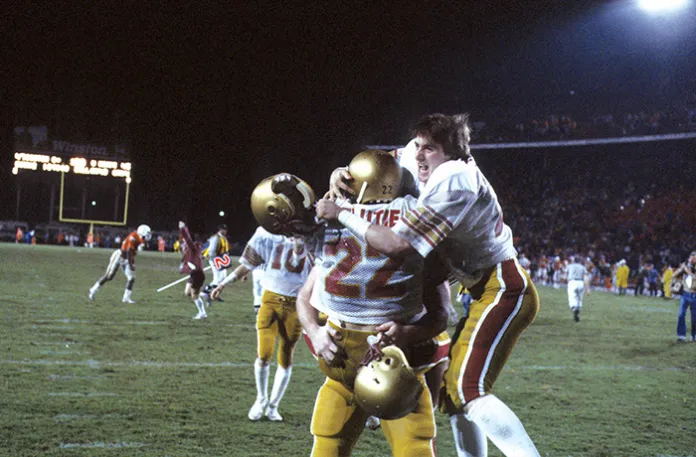

In the penultimate chapter, Klosterman describes walking in on his father watching the end of the November 1984 matchup between Boston College and the University of Miami, immortalized as the “Hail Flutie” after a seemingly impossible last-chance heave by Boston College’s diminutive cult hero quarterback, Doug Flutie, hit pay dirt in the end zone.

THE NCAA’S OLD RULES BROKE COLLEGE SPORTS

“Boston College played hard, but this one is over,” the elder Klosterman declared just before Flutie’s now-legendary 65-yard game-winning Hail Mary. Klosterman then recalls his father saying something decidedly out of character in its introspection, coming from a North Dakotan of the Silent Generation: “Well, there you go. I gave up, but he did not. And that’s why he is who he is, and that’s why I am who I am.”

He chalks the declaration up to his father’s possibly subconscious self-awareness that both he and his son were, like Exley in A Fan’s Notes, doomed to a life on the outside, barred from glory by their obsessions with the past and depressive workaholism. The triumph of Football is to show, contrahyper-realists such as Belichick and Saban, how much the sport needs its dreamers, spectators, and fans.

Derek Robertson is a writer based in New York.