George Cabot Lodge, the scion of one of America’s most enduring political dynasties, stepped into the arena against a Kennedy in 1962, marking the final chapter in a familial rivalry that had defined Massachusetts politics for generations. His defeat at the hands of Edward M. Kennedy did not dim his drive; instead, it propelled him toward a distinguished career in academia, where he challenged conventional wisdom on business, government, and global economics with the same tenacity he brought to the campaign trail.

Born on July 7, 1927, in Boston, Lodge entered the world amid the weight of legacy. He was the elder son of Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the Republican senator who had famously lost his seat to John F. Kennedy in 1952, later serving as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and South Vietnam, and as Richard Nixon‘s vice presidential running mate in 1960. His mother, Emily Sears Lodge, came from a prominent Boston family. Lodge’s patrilineal great-grandfather, Henry Cabot Lodge Sr., had secured the same Senate seat in 1916 by defeating John F. Fitzgerald, the maternal grandfather of the Kennedys. From an early age, politics coursed through his veins, but so did a love of the sea — he began sailing at age six and remained an avid mariner throughout his life.

Educated at the elite Groton School, Lodge enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1945, serving until 1946 as World War II drew to a close. He then attended Harvard College and graduated cum laude in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree. A stutter in his youth steered him away from oratory-heavy pursuits, leading him instead to journalism. He joined the Boston Herald as a political reporter and columnist, honing his skills in dissecting the intricacies of power and policy.

In 1954, Lodge transitioned to federal service, becoming director of information at the U.S. Department of Labor. Four years later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him assistant secretary of labor for international affairs — a position he retained under President John F. Kennedy in 1961. As the U.S. delegate to the International Labour Organization, he was elected chairman of its governing body in 1960. His work focused on labor’s role in developing nations, culminating in his first book, Spearheads of Democracy: Labor in the Developing Countries (1962). Accolades followed: He was named one of the 10 outstanding young men in the U.S. by the Junior Chamber of Commerce, received the Arthur S. Flemming Award as one of the top young federal employees, and earned the Department of Labor’s Distinguished Service Award.

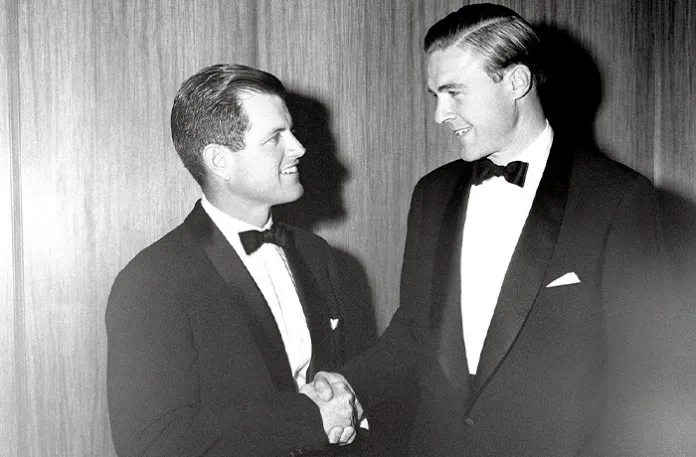

That same year, 1961, Lodge accepted a lectureship at Harvard Business School. But politics called. In 1962, he secured the Republican nomination for the special Senate election to fill the seat vacated by John F. Kennedy’s ascension to the presidency. Facing Edward M. Kennedy, the youngest brother making his political debut, Lodge campaigned vigorously on issues such as civil rights, foreign aid reform, and unemployment. He mobilized 5,000 volunteers, with only his driver on payroll. Despite the effort, he lost by a margin of 55% to 42% (with the remainder of the vote going to minor candidates). The race closed the Lodge-Kennedy saga.

Undeterred, Lodge returned to Harvard Business School in 1963. He advanced to associate professor in 1968 and earned tenure in 1972. As the Jaime and Josefina Chua Tiampo Professor of Business Administration, he co-created the influential Business, Government, and the International Economy course, which became a cornerstone of the curriculum. His research spanned global issues: In the 1960s, he helped establish the Central American Institute of Business Administration, now a premier institution. Articles in Foreign Affairs spurred the creation of the Inter-American Foundation, where he served as vice chairman for seven years.

Lodge authored or co-authored numerous books critiquing American economic ideology and advocating adaptive business-government relations. His key works include The New American Ideology (1975), which won the Academy of Management’s annual book award in 1995; The American Disease (1984); U.S. Competitiveness in the World Economy (co-edited, 1984); Ideology and National Competitiveness (co-edited, 1987); Perestroika for America (1990); Managing Globalization in the Age of Interdependence (1995); and A Corporate Solution to Global Poverty (2006). He published over 40 articles, including 12 in the Harvard Business Review, two of which earned McKinsey Awards. In his post-retirement career as a professor emeritus, he served on the board of Nordic American Tanker Shipping until 2007 and remained a member of the Council on Foreign Relations since 1959.

Lodge’s life bridged the corridors of power and the classrooms of inquiry, always questioning the status quo with intellectual rigor. He died on Jan. 4, 2026, at 98. Reflecting on his Senate run, he captured the essence of his unflinching spirit: “You get so obsessed with campaigning that victory or defeat isn’t the name of the game. The name of the game is doing your damnedest.” In politics or academia, Lodge always did.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and the Allen and Joan Bildner Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University. Find him on X @DanRossGoodman.