There is an oft-repeated internet maxim, usually attributed to George Orwell or Voltaire but actually coined by a neo-Nazi, that goes as follows: “To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize.” This is a very silly idea. Well-entrenched ruling classes are usually quite comfortable with mockery, humor, and criticism precisely because they are secure in their status. In the middle decades of the 20th century, America’s WASPy elite was just such a class. It found itself at the head of a global superpower.

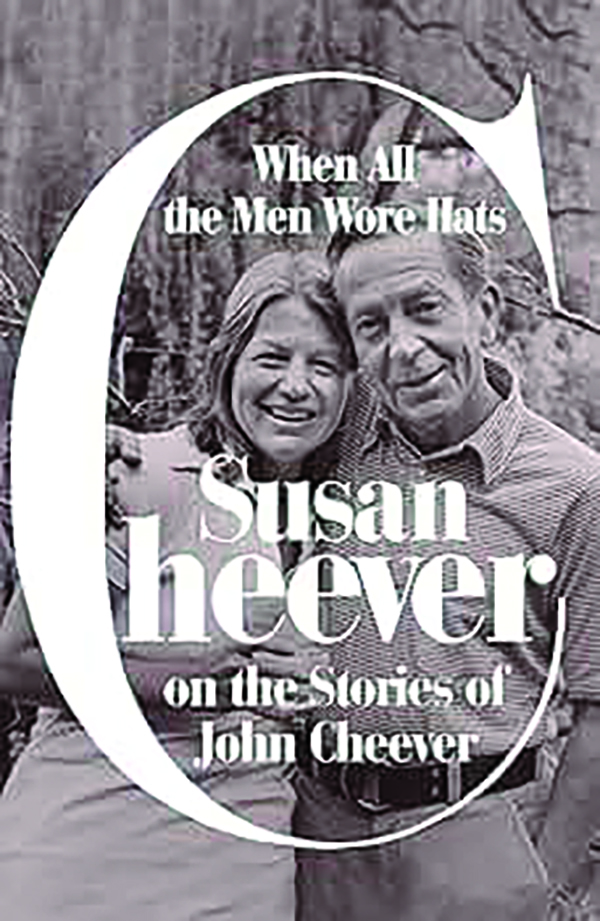

Enter John Cheever, whose short stories were by turns affectionate, funny, and critical portraits of a group that has since receded from public consciousness. Today, we can’t seem to decide if the WASPs were old-fashioned stuck-ups or wise statesmen whose passing should be lamented. The title of When All the Men Wore Hats, Susan Cheever’s memoir-cum-reflection on her father’s short stories, gets at this ambiguity. The younger Cheever obviously admires these stories and can’t help but romanticize certain aspects of mid-century American life. But she also feels compelled to reveal all sorts of salacious details about her father and his intimates. Naturally, Susan Cheever is one of the baby boomers, the generation that unseated the WASPs from their privileged perch.

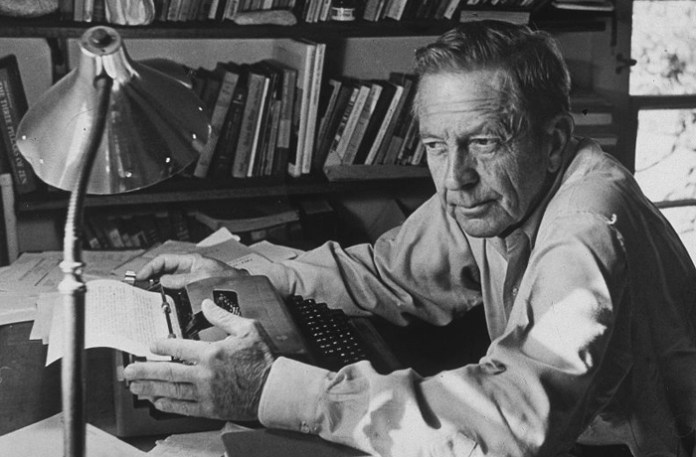

John Cheever, as his daughter relates, was not born into fabulous wealth or privilege, but he was kicked out of a Northeastern prep school, and his writing and persona captured something essential about the WASP ethos. Like most of his contemporaries, he was private to the point of withdrawal, but was also fascinated by the tension between outward appearance and inner turmoil. When All the Men Wore Hats reveals that his writing was often connected to personal struggles with infidelity, alcoholism, and money. As Susan Cheever discusses the stories, a familial rift emerges between the father’s old-fashioned attitude, which prized discretion, restraint, and, yes, a certain amount of repression, and the daughter’s let-it-all-hang-out sensibilities.

Cheever the elder insisted on a sharp distinction between fiction and real life. His daughter bridles at this artificial boundary, drawing obvious parallels between her father’s personal struggles and some of his best-known work. This argument goes back a long time: she noticed at a young age that the little girls in her father’s stories were strangely familiar.

If John epitomized the buttoned-up WASP temperament, Susan is the quintessential boomer, from her education at a progressive Vermont boarding school, to her frank discussion of family secrets, to her own memoir on sex addiction. Does her airing of family laundry, dirty and otherwise, add to the stories themselves? Devoted Cheever fans will surely be interested in certain details, such as the fact that “The Five-Forty-Eight,” one of six stories included at the end of the book, was inspired by two of John Cheever’s own favorites, O. Henry’s “The Ransom of Red Chief” and Ernest Hemingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” In turn, his story inspired “The Train,” a sequel by Raymond Carver. This literary genealogy is woven into the younger Cheever’s memories of growing up in suburban New York, where the local train station was her father’s lifeline to the city.

Other connections are less interesting. John Cheever may have receded from the popular imagination, but his stories are still reliable fodder for middlebrow TV — many have pointed out that the new prestige drama Your Friends & Neighbors shamelessly borrows its premise from “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill.” Susan Cheever clearly thrills at the fact that her father was an inspiration for Mad Men, at one point declaring, “I am Sally Draper,” the eldest daughter of the show’s hard-drinking and serially unfaithful protagonist. But Mad Men, for all its fealty to the John Cheever lifestyle of booze, grey suits, and infidelity, often indulged in artless storytelling, something you would never find in the source material. Its viewers were routinely invited to tut-tut characters for everything from their retrograde views on race and gender to their chain smoking. At one point in the show’s second episode, Betty Draper (January Jones), wife of the mysterious protagonist, actually stares at her sleeping husband and whispers — I kid you not — “Who’s in there?” Going from a John Cheever story to a Mad Men episode is like replacing a carefully stirred martini with a shot of cheap gin.

Just as the WASPs were dethroned by a rising generation with little regard for the old way of doing things, Susan Cheever’s own cohort is now in the process of being replaced. “Boomer,” a word once inextricably linked to rebellion and youth culture, has become a term of derision for millennials and Generation Z, who resent their elders’ stranglehold on the culture just as fervently as the boomers once despised the WASPs. Susan seems to feel the younger generations’ breath on her neck, sprinkling anachronistic phrases such as #MeToo and “toxic masculinity” throughout the book. At times, she seems to be rewriting the past to make her father more palatable to modern readers. In her 1984 memoir Home Before Dark, Susan described her father as bisexual. In this latest book, he has become gay, despite his sexually active marriage and numerous affairs with women. John Cheever slept with plenty of men — his published journals and his daughter’s own remembrances make that abundantly clear — but one gets the sense that the complexity of his sex life has been flattened for a modern audience.

Other parts of the book suggest that Susan Cheever doesn’t actually share her younger readers’ tastes and ideological assumptions. Blake Bailey, the Cheever biographer who was summarily canceled during the #MeToo purge, is repeatedly and approvingly cited throughout. When All the Men Wore Hats can’t decide if it wants to stay faithful to its boomer roots or embrace the more prurient sensibilities of younger readers and critics.

MAGAZINE: HAS KARL OVE KNAUSGAARD LOST IT?

What’s left is an inessential account of the author’s upbringing that is occasionally interesting but often wince-inducing, as more details tumble out about John Cheever’s troubled marriage, his chronic financial difficulties, and his difficult relationships with everyone from his editors to his older brother Fred. While it’s interesting to read about the backyard pools in Ossining that inspired “The Swimmer,” still probably the best-known of his short stories, these biographical details are hardly necessary to appreciate the actual writing.

So what’s worth salvaging from the Cheever family corpus? Well, the original stories still stand apart. Modern storytelling is getting cruder by the minute, but John Cheever, the master of the arch remark, the raised eyebrow, and the minute hand gesture, retains his subtle allure. Younger readers don’t actually need to know anything about the author or his daughter to appreciate these stories, which brings us back to the WASPs, who appreciated discretion, a good martini, and the fact that sometimes, less is more.

Will Collins is a lecturer at Eotvos Lorand University in Budapest, Hungary.