If you’ve ever thought that pretty much everything that could be said about the coming of the Civil War had already been said, this book will prove you wrong. In adding significantly to what we thought we knew, it changes what we did know. What’s more, it brings to the fore a subject—verbal abuse and physical violence, rooted in politics, on the floor of the United States Congress—that has never received the attention that Joanne Freeman brings to it. A superb, serious, authoritative, lively, occasionally amusing work of scholarly bravura, her book is also timely—although today’s circumstances, not the author, make that so. Only a few paragraphs hint at our present discontents.

The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War has been in the making for almost two decades. Its origins lie in the author’s long-held interest in the history of violent behavior and our national government. Her previous book, Affairs of Honor (2001), covered the subject during the early history of the republic. Here, she picks up the story in the 1830s. The results are revelatory.

Few people can be unacquainted with reports and photos of brawls in other countries’ legislatures. But not here is our reassurance to ourselves when we see such spectacles. We prefer to think that, save for an errant verbal assault—like the “You lie!” that South Carolina’s Joe Wilson launched at President Barack Obama during a congressional address in 2009—our representatives are beyond such outbursts. And that with the exception of a stray incident here or there—as when Alaska’s Don Young pushed John Boehner against a wall and held a knife to his neck—they are certainly beyond physical assault.

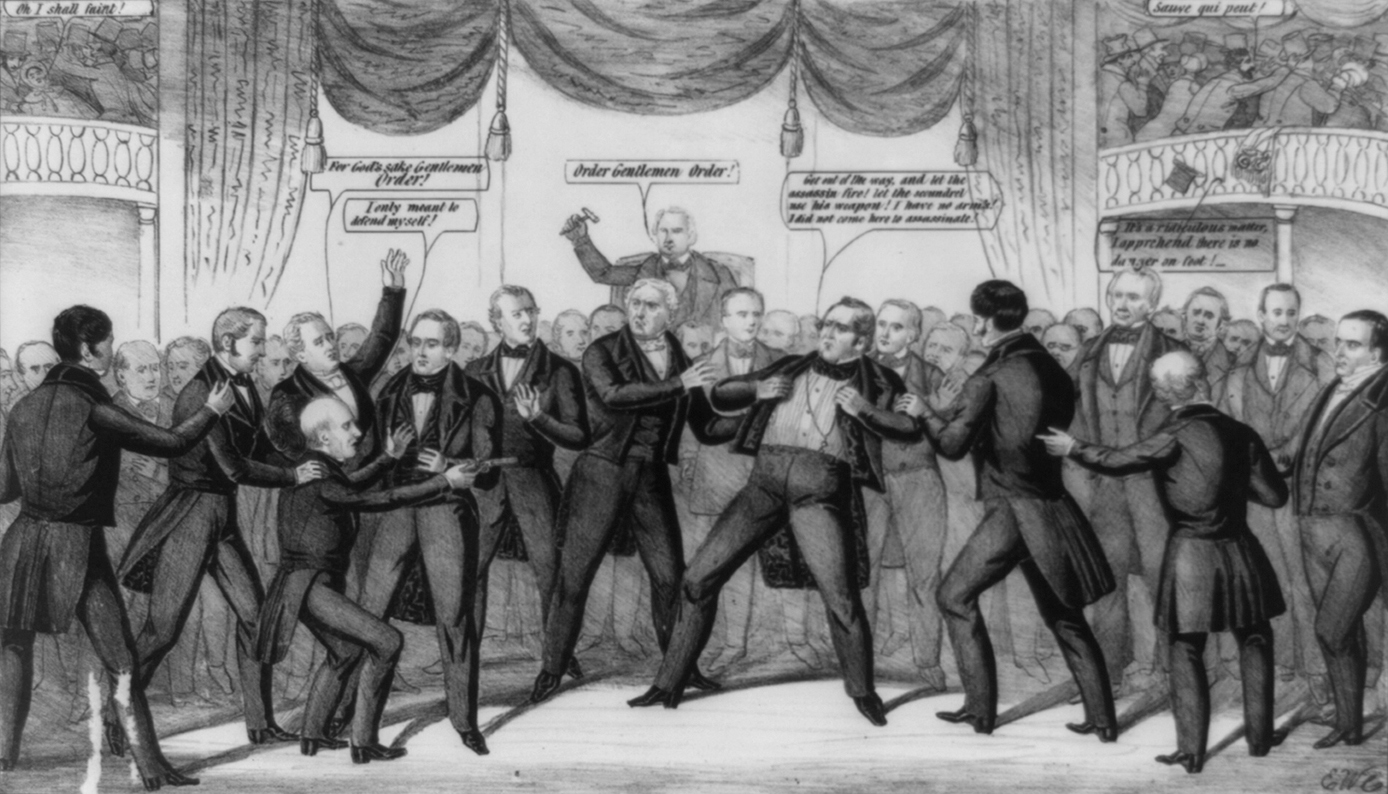

Yet as Freeman shows, in pre-Civil War congresses, especially in the House of Representatives, “fighting was common enough to seem routine.”

As early as the 1790s, members of Congress took up cudgels against each other. In 1798, two weeks after Vermont congressman Matthew Lyon spat in Connecticut congressman Roger Griswold’s face during debate, Griswold went after Lyon with a cane. The most infamous such incident occurred in 1856 when South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks entered the Senate and caned Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner senseless for having repeatedly taunted the South over slavery.

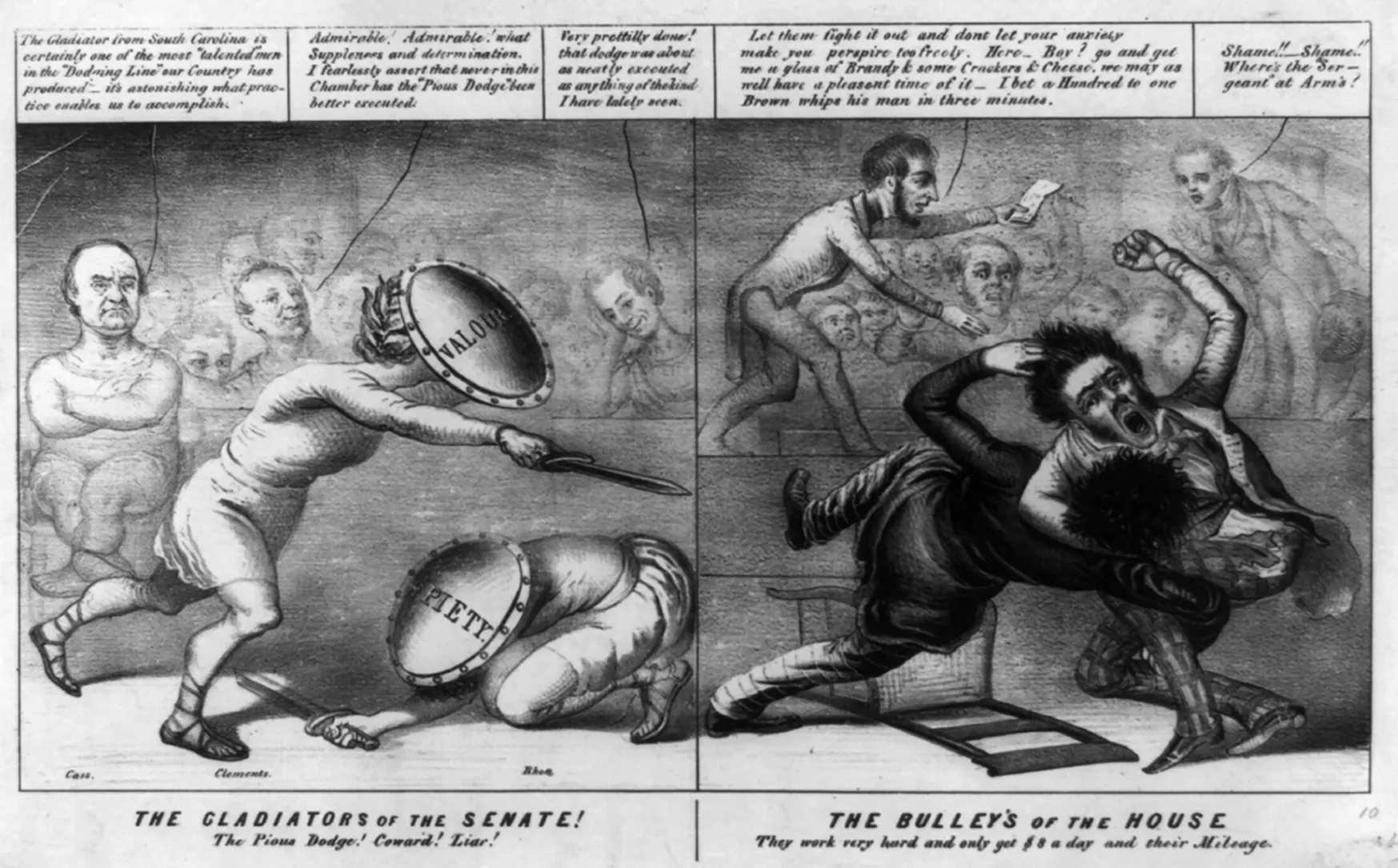

Yet as it turns out, there were many more such incidents. Freeman seems to have exhumed the records of all of them. No Congress after the 1830s until the war was without a physical assault, and they rose in number as time went on. Heavy drinking increased their severity. Most of them—with fists, bricks, bowie knives, pistols, and rifles—were initiated by Southerners increasingly agitated by antislavery petitions to Congress, the growth of antislavery politics, and the antislavery press. The sheer number and violence of the incidents that Freeman brings to light, all-out brawls as well as individual combat, reveal an institution often out of control, only brought back from the brink of collapse by members with superegos stronger than those of Griswold and Brooks. Freeman’s Congress is scarcely the arena of soaring rhetoric and classic argument that we associate with the names of Clay, Webster, and Calhoun. It’s a pit of violence.

The violence was not limited to indoors. When congressional rules and sober representatives succeeded in prevailing against threats to life and limb in the House and Senate, attacks often spilled onto the capital’s streets. Some of them, like duels—a frequent resort when honor was impeached—followed rough, age-old conventions, the kind that Freeman dealt with more comprehensively in her earlier book. The most notorious duel of the antebellum era was fought in 1838 between Maine Democratic congressman Jonathan Cilley and Kentucky Whig William J. Graves, an affair of honor that, Freeman suggests, helped initiate an almost quarter-century of growing partisan, then inter-sectional, violence. Freeman’s unsurpassed knowledge of duel culture is in evidence in her telling of this confrontation. Fought with rifles, it cost Cilley his life.

Less formal out-of-doors set-tos were more frequent. Representatives attacked other representatives, and members of the public, some waiting in ambush, went after elected officials on city streets. Provocations were not limited to one party or section: Southerners had frequent recourse to the honor defense only because some Northerners—John Quincy Adams and Sumner the standouts among them—were masters of the clever taunt, brilliant orators, and manipulators of congressional rules whom intimidation couldn’t silence.

To bring to light this forgotten history, Freeman has burrowed deep into the archives—from the often taxing-to-read pages of the Congressional Globe (that era’s version of the Congressional Record) to collections of members’ preserved correspondence. Frequently, however, these documents hide facts behind conventions of discretion and circumlocution. To go beyond the hints of threatened and successful assault, Freeman has masterfully teased out what she can from other sources. In doing so, she places most attention on a likable figure whom she clearly admires and makes her readers admire, too.

He’s Benjamin Brown French, a native of New Hampshire, a newspaperman, a writer, a Democrat, and a little-known figure of pre-Civil War Washington. While never holding federal elective office, French was close to New England Democrats (including President Franklin Pierce) and long served on the House staff before becoming clerk of the House. Widely admired, he served as president of the District of Columbia city council, grand master of the District’s Masons, and grand master of the Knights Templar of the United States. He laid the cornerstones of the Smithsonian Institution building and the Washington Monument and composed the poem read at Gettysburg the day that Abraham Lincoln delivered his celebrated address there. He also had “an uncanny knack for being in the right place at the right time”—the day’s Zelig, a spectator at Andrew Jackson’s near-assassination, John Quincy Adams’s fatal stroke on the House floor, and Lincoln’s bedside after he was shot by John Wilkes Booth.

For years, French saw events close up in the House and came to know everyone in town. A clubbable, witty man of sunny disposition, disenthralled by human nature, liked and trusted by almost everyone, he was also a fair appraiser of public affairs. Most important for posterity’s use, he recorded most of what he witnessed in a diary—one that amounted to 11 volumes. Mining the diaries for everything they’re worth, Freeman places French at the center of her tale.

It’s a many-faceted tale. It’s about the institution of Congress: its workings, its culture, and its rules. We see how its members had to adapt to the increasingly sectional, partisan press whose national reach grew with changes in reportage, technology, and distribution and whose editors often had to face sectional fury and threat. We’re introduced to Congress’s rowdiness, noise, and drunkenness, its galleries filled with onlookers, many of them women, to whom senators and representatives played. All come alive under French’s pen, to which Freeman adds her own perceptive, often humorous, glosses.

The tale is also about honor culture—a subject that Freeman knows as well as anyone else. We witness the growing brittleness of men caught on the horns of the dilemma of escaping possible death or being dishonored, shamed, and humiliated for choosing a wiser course and standing down.

And it’s about bullying—members, overwhelmingly Southerners, trying to silence their opponents by threat. Never again will historians be able to write about the coming of civil war without taking account of the role of bullying abuse on the floor of Congress and outside. It was everywhere, especially in the House. Some, like the notably egregious Southerners Henry Wise and Henry S. Foote, were trigger-happy masters of invective who could send their adversaries into paroxysms of rage and despair. Bullying, especially by Southerners, became a method of governance by threat. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but it was always in the air, poisoning relationships, heating debates, and inescapably embittering the nation’s increasingly toxic politics. In reading this book, you wonder whether the union might have been saved but for unbridled congressional intimidations.

Here is where The Field of Blood gains its greatest significance. It puts honor culture and Southern bullying at the heart of the course to the Civil War. It doesn’t diminish the causal importance of slavery and abolitionism in bringing on the conflict. It doesn’t remove territorial expansion, the spread of slavery, the market economy, or differences between Northern and Southern culture from the mix. Instead, in Freeman’s words, the story is not so much about the rules of the game but about “the game gone awry.”

And here’s where Benjamin Brown French is illustrative. His trajectory from nationalist Democrat to Northern Republican, from the loyal member of one party to the adherent of a new one, from a nationalist who saw things in partisan terms to one who saw things in sectional ones illustrates how the fraying of the norms of governance helped bring on civil war. French both added to and was swept along by the momentum toward war.

He started out his political career as a “doughface” Democrat—a Northern partisan who, dodging realities, tried his best to accommodate Southern slave power so as to maintain his party’s hold on federal offices. Over time, however, a spectator to growing Southern truculence and bullying, his sectional identification began to take hold. Even as it did so, he had to watch Northern congressmen continue to give way before Southern threats. Not until the late 1850s, with the emergence of the Republican party—an emergence significantly fueled by Brooks’s caning of Sumner—did congressional Northerners of both the Democratic and Whig parties begin to stand firm against Southern bullying. They did so first by meeting “strut with strut,” then by invoking their right of free expression. They would be silenced no more.

Much of the North’s newfound confidence was born on the floor of Congress. This was, writes Freeman, “the most dramatic innovation in congressional violence after 1855: Northerners fought back.” It proved a bracing strategy, even if it made Congress an “armed camp.” It forced French to become a Republican, albeit a moderate one, and cost him his lifelong friendship with Franklin Pierce. With Lincoln’s election, it became a strategy that evinced the determination to yield no more. The North would fight for its own rights.

Freeman’s research is prodigious, her scholarship unimpeachable. By shifting her gaze from the conventionally cited causes of the Civil War, she has deepened our understanding of its coming. She doesn’t discount these other sources of disunion. Instead, she draws attention to the realities of governance—its rules, processes, and ethos—and to the way their degradation can spill beyond institutions to affect, in this case fatally, wider public life. “Congressional violence didn’t cause [the] sectional standoff, but it intensified it.” America, she writes, “was backing its way into civil warfare.”

It remains for Freeman or someone else to bring together how the two eras that Freeman has now covered can, or should, be seen as a whole in respect to violence among federal and other officeholders. And whether the mid-19th-century congresses were any more violent than other countries’ legislatures, then or since, is a subject yet to be explored—one that could greatly enrich our understanding of representative government and of human nature itself.