Nearly half a century ago, when I was a preschooler in Soviet-era Moscow, two thick magazines appeared in our home. They had plain, pale-tan covers, but I could tell they were quite special to my parents. In those magazines’ pages was a riveting story—what I could understand from my precocious attempts at reading it at the age of 5 or 6. Years later, when I read it properly, some things still lived on in my memory: a huge, talking black cat that walks on its hind legs; a lady who becomes a witch and flies naked on a broomstick; a magician’s globe that could come alive and zoom in on a single matchbox-sized house with minuscule human figures inside.

It was one of the greatest novels of the 20th century: The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1891-1940), first published in a censored version in the literary magazine Moskva in November 1966 and January 1967, nearly 30 years after it was written. (With 150,000 copies in print, demand was huge; it was a year or two before my parents got the coveted magazines.) Soon after, the uncut novel was published as a single volume by the emigré-run YMCA Press in Paris. And in the fall of 1967, not one but two English translations came out in the United States: Mirra Ginsburg’s from the censored edition and Michael Glenny’s from the full text.

The Master and Margarita was a major sensation in the Soviet Union, and in the 50 years since its publication in the West it has become an extraordinary international phenomenon. It has been translated into over 40 languages, with 4 more English translations since 1990. It has inspired songs, apparently including the Rolling Stones’ 1968 “Sympathy for the Devil,” as well as operas and musicals. (Andrew Lloyd Webber was tempted about a decade ago but gave up the project as “undoable”—although the novel’s secondary plot may have influenced Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar.) Stage versions of The Master and Margarita have been produced by more than 500 theater companies around the world; the most recent American production, at New York’s off-off-Broadway West End Theatre, ran in August and September. The novel has had a handful of screen adaptations, and there is talk of a Hollywood feature in collaboration with a Russian producer.

How to describe The Master and Margarita? Winston Churchill’s quote about Russia comes to mind: “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The story is fantasy and magic ranging from farcical deviltry to high mysticism to horror. It is riotously funny, with moments of both high and low comedy. It is mordant social satire, vividly portraying Moscow life in the mid-1930s. (The novel, on which Bulgakov worked from 1928 until his final days, mentions no dates and contains contradictory clues pointing to 1934-36 as the likely timeframe.) It is a novel of philosophy and religion, with a story-within-the-story that offers a unique revisionist account of Pontius Pilate’s role in the crucifixion of Jesus. It is a poignant love story. It is a story about literature, creative freedom, and the conflict between the artist and the repressive state—in which the artist wins against all odds. It has a usually omniscient narrator who often becomes an “I” speaking to the reader—wryly, or wistfully, or bitterly, or with dread and despair, or even from the deadpan standpoint of an upright Soviet citizen channeling the politically correct position.

One of The Master and Margarita’s peculiarities is that the title characters take a while to show up: The Master, a persecuted writer who is now a mental patient, appears more than a third of the way into the book (in a chapter titled “Enter the Hero”), and his lover Margarita even later. The novel’s first part focuses largely on the supernatural and satirical tale of the Devil visiting Moscow as Professor Woland, a foreign consultant and expert on black magic.

In the opening pages, Woland appears to two Soviet littérateurs, the brash young poet Ivan Bezdomny (a pseudonym meaning “homeless,” a gibe at the virtue-signaling pen names of the post-revolutionary era) and the slick editor Mikhail Berlioz, while they sit on a park bench discussing atheist propaganda literature. The eccentric stranger engages the duo in a debate on God, humanity, and the existence of Jesus (which takes a detour into the tale of Pontius Pilate’s encounter with a strange prisoner named Yeshua). Mocking Soviet clichés about how “man himself” controls the world, Woland points out the unpredictable fragility of human life—and informs Berlioz he is about to die by beheading. The two friends conclude the “foreigner” is mad; but the prediction promptly comes true when Berlioz slips and falls under a streetcar.

More mayhem follows from Woland’s minions: the buffoonish trickster Koroviev, Behemoth the cat, and the thuggish Azazello. There’s a scandalous magic show at a Moscow music hall, the fallout from which includes disappearing couture clothes and money that turns to scrap paper. Various boorish and corrupt Soviet officials, from a building superintendent to a gaggle of art and entertainment functionaries, get their comeuppances. (One bureaucrat temporarily vanishes, leaving behind a talking empty suit that proves perfectly up to the job.)

Meanwhile, Ivan’s efforts to apprehend the devilish gang land him in a mental hospital; that’s where he meets the self-styled “Master,” a brilliant, broken man who voluntarily sought refuge at the clinic after several months in prison. The Master ran afoul of the regime when he wrote a novel about Pilate and Jesus and got an excerpt published—causing him to be hounded in the press as a stealth Christian propagandist and eventually arrested.

The Master’s past also includes a chance meeting with an unhappily married woman who becomes his “secret wife.” That woman, Margarita, is at the center of the novel’s second half. Still grieving for the Master after his arrest, she finds herself thinking she’d pawn her soul to the Devil just to find out if he is alive; lo and behold, that can be arranged. Soon, Margarita is flying naked over Moscow by night, wrecking the apartment of a critic named Latunsky who instigated the Master’s persecution, and finally playing hostess at Satan’s ball for endless multitudes of the damned.

Her Faustian bargain has a happy ending. The Master is restored and so is his novel, which he had burned in a fit of despair; as Woland remarks in what may be the book’s most famous line, “Manuscripts don’t burn.”

That novel is the same story Woland began in the first chapter; it is woven throughout The Master and Margarita, continuing as Ivan’s troubled dream and finally as two chapters from the Master’s resurrected manuscript. In the Master’s novel, Pilate is a bitter, weary bureaucrat, deeply moved by his encounter with the battered prisoner who speaks of love and human goodness and who can somehow soothe the Roman’s excruciating migraine. Yet Pilate will not risk his career to save the itinerant preacher—and stands harshly condemned when he learns of Yeshua’s last words before the crucifixion: that among human vices, “one of the worst is cowardice.”

Toward the end, The Master and Margarita’s two worlds merge. Yeshua’s messenger comes to ask Woland to grant “peace” to the Master and his love. (Their reward is a humanist’s heaven: an eternity in a charming cottage filled with books and music.) And it is up to the Master to release Pilate from his prison of immortal solitude and remorse.

* *

The Master and Margarita’s many layers of meaning can be, and have been, endlessly discussed. The Master’s tale has a strong autobiographical component, both in its romantic side—Bulgakov and his wife Elena met while married to other people—and in its depiction of the embattled writer under the Soviet regime. In the late 1920s, Bulgakov was viciously attacked in the press, mainly for his hit play The Days of the Turbins, a sympathetic treatment of an aristocratic family during the Russian civil war. Savaged by critics and muzzled by censorship, he plunged into depression, feeling that his writing life was over. In a “meta” twist, the actual manuscript he burned at a particularly low point was the first draft of the novel about the Devil that would later become The Master and Margarita.

Bulgakov’s scathing portrayal of the Soviet literary elite was rooted in personal experience, and there is probably a bit of revenge fantasy in Berlioz’s gruesome death and in Margarita’s gleeful trashing of the critic Latunsky’s apartment; both characters had specific and odious prototypes. But it is also a larger indictment of what Orwell called “the prevention of literature” by ideological diktat. The system crushes the true writer and breeds cliché-spouting mediocrities. The Master doesn’t need to read the poetry of “Comrade Homeless” to know it’s dreadful—“As if I haven’t read others,” he says—and after a moment’s reflection Ivan must admit that he’s right.

No less prominent a theme is the Soviet police state whose omnipresence casts a shadow feared even by loyal citizens: When the sleazy theater manager who shares a communal apartment with Berlioz discovers that his housemate’s rooms are sealed, he instantly assumes Berlioz has been arrested and starts nervously recalling a possibly inappropriate, “entirely unnecessary” conversation the two had recently had. (The Jerusalem chapters echo this motif: Here, Judas is not a treacherous disciple but a paid informant who lures Yeshua into a conversation deemed insulting to the emperor.)

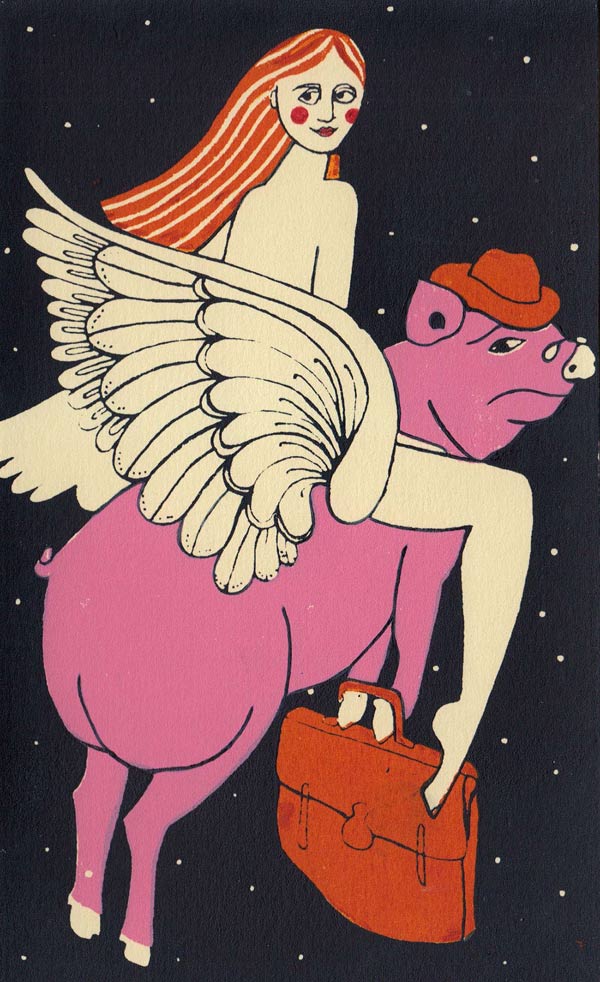

Margarita’s housemaid Natasha rides nude on the back of Margarita’s bewitched, enswined neighbor Nikolay Ivanovich. [Sasha Moxon]

Yet much of The Master and Margarita lies in the realm of ambiguity. Is its Satan a charismatic villain, a tempter—or an enforcer of justice? (Among Bulgakov’s working titles was The Great Chancellor.) The book’s epigraph, from Goethe’s Faust, describes the devil as “part of that power which eternally does good whilst eternally desiring evil.” But Woland, who often clearly expresses Bulgakov’s own views—with a dark sarcastic edge—does not even seem to desire evil; his victims almost invariably deserve their punishment, and he does, in the end, prove to be a savior to Margarita and the Master. That their ultimate fate is arranged with the forces of Heaven hints at a metaphysics in which darkness and light serve the same ends as part of the balance of the universe: The Devil simply happens to be in charge of its shadow side.

There is also some intriguing speculation about Woland’s real-life parallels—including Stalin, who sometimes acted as Bulgakov’s quasi-patron, easing the ban on his work and helping him get theater jobs in the early 1930s. “All-powerful!” exults Margarita when Woland restores the Master’s manuscript; perhaps, on some level, Bulgakov saw Stalin that way and reimagined him as Woland, a dark ruler who yet has genuine nobility and even mercy. Another candidate is U.S. ambassador William C. Bullitt, whose lavish spring ball in Moscow in 1935 was the basis for Woland’s ball; Bulgakov, denied permission to go abroad, may have seen Bullitt as a potential rescuer who could spirit him to freedom as Woland does his heroes.

Bulgakov’s overall treatment of religion, too, allows multiple readings. The novel was partly inspired by Bulgakov’s revulsion at the Soviet regime’s crude atheist propaganda; while the foreword to the first Soviet edition of the complete text in 1973 gamely tried to explain that the author’s barbs at militant atheism were actually directed at cynics who exploit atheism to justify amorality, this was a transparent ploy to appease the censors.

But is The Master and Margarita a defense of religion? Its Jesus is highly unorthodox: he has just one disciple, Matthew Levi, and there is no hint at his special mission, divinity, or resurrection. (Moreover, he complains that Matthew—presumably the evangelist—writes down a hopelessly garbled version of his teachings.) Yet Matthew’s appearance as Yeshua’s messenger to Woland near the end clearly implies that Yeshua is now the King of Light to Woland’s Prince of Darkness. And other moments have a more traditional if subtle religious symbolism, as when Ivan arms himself with a candle and a small icon and takes a baptismal swim in the Moskva River at the start of his chase after Woland’s gang, which also turns out to be the beginning of his spiritual transformation.

* *

In the Brezhnev-era Soviet Union, The Master and Margarita was a subversive bombshell. Its discussion of religion and atheism alone was utter heresy—to say nothing of its ruthless skewering of official Soviet literature, its candid portrayal of fear in a repressive society, and its pointed satire of the socialist consumer sector, where service is delivered with either a sulk or a scowl and the food at a theater café is of “second-grade freshness.” Today, Bulgakov’s masterpiece is a recognized Russian classic; in a 2009 survey, a striking 16 percent of Russians named it their favorite book, by far the single most popular choice.

Even more striking, perhaps, is the book’s staying power in the West—which baffles many Russians, given the cultural specificity of its setting and especially its humor. Yet Bulgakov’s key themes have universal resonance: the destructiveness of tyranny and the supremacy of the individual’s inner freedom; the corruption of creative work by ideological pressure (a theme sadly relevant in the West today); the power of forgiveness. And his genius at blending the psychological and the fantastic, the mystical and the mundane, the sublime and ridiculous transcends cultural barriers.

It is a testament to The Master and Margarita’s enduring appeal that it recently inspired a literary tribute by an American: Mikhail and Margarita, a debut novel by Massachusetts writer Julie Lekstrom Himes, which gives Bulgakov’s novel a fictional backstory involving a woman named Margarita, the poet and gulag victim Osip Mandelstam, and Stalin himself. Himes’s novel is elegantly written and well-crafted, though there is something odd about fictionalizing the well-documented life of a real person from the fairly recent past; it’s one thing to give Bulgakov a face-to-face meeting with Stalin (instead of their real-life telephone conversation), quite another to invent a friendship with Mandelstam and a romance drastically different from the real one. Nonetheless, Mikhail and Margarita makes for an interesting read, both as a curio and as a modern take on Bulgakov’s central motifs of love and art, freedom and fear.

The Master and Margarita’s American (and British) life is all the more remarkable given that all the English translations published so far are wanting. Translating a book whose language has so much verve, poetry, and nuance is a daunting task; all the translations rise to the challenge brilliantly at places but fail dismally elsewhere. Outright mistranslations crop up; Glenny even botches a key line of dialogue, translating Ivan’s admission to the Master that his verses are “horrendous” as “Stupendous!” The recently reissued 1997 translation by the controversial husband-and-wife team of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky has the fewest inaccuracies, but their effort to preserve the original wording leads to such monstrosities as “Who here is ‘Prosha’ to you?” instead of “Who do you think you’re calling Prosha?”

Overall, the 1995 version by Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O’Connor is probably the best; it still suffers from stilted language and clumsy dialogue but comes closest to capturing the flavor and spirit of the original.

Perhaps someday, a new translation will get it right. Until then, the success of The Master and Margarita in English proves that just as manuscripts don’t burn, truly great books don’t get lost in translation.

Cathy Young is the author of Growing Up in Moscow: Memories of a Soviet Girlhood.