Who broke the Beatles, and when? Some say it was the night when John violated the unspoken code of the Moptops by bringing Yoko to Abbey Road. Others, that it was soon after that, on the night when Yoko, who had been sleeping beneath the mixing desk, emerged to steal one of George Harrison’s personal stash of chocolate digestive biscuits, and George, who was the spiritual one, shouted, “You bitch!” Perhaps it was when Ringo, sick of the endless studio jams, bad vibes, and general lack of appreciation, walked out and the others, showing how little they appreciated him, took turns at playing the drums. Or was it when Paul forced them to play “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” for three days straight?

All four of those crises occurred at Abbey Road Studios between May and October 1968, while the Beatles were recording The Beatles, the double album that they and everyone else came to call The White Album. I blame “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” and not just because reviewing the six CDs and Blu-ray disc of the 50th-anniversary box set of The White Album involves hearing Paul’s idea of comedy ska in pristine and appalling Dolby True HD 5.1, alternate takes and all. The creation, recording, and release of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” represent everything that broke the Beatles. Together with Lennon’s sonic collage “Revolution 9,” it explains why The White Album may well be the best Beatles album and why it has some of the worst Beatles music.

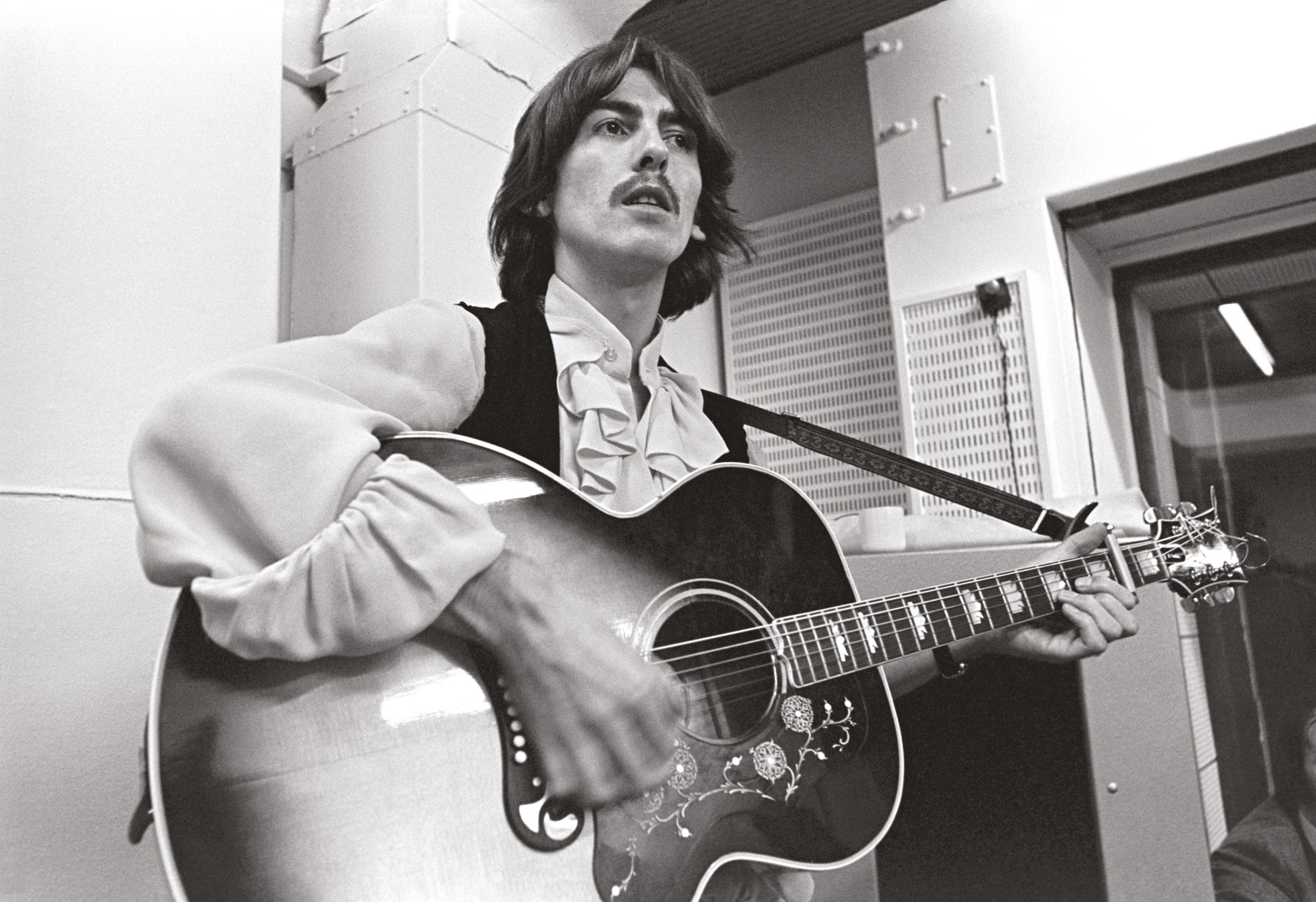

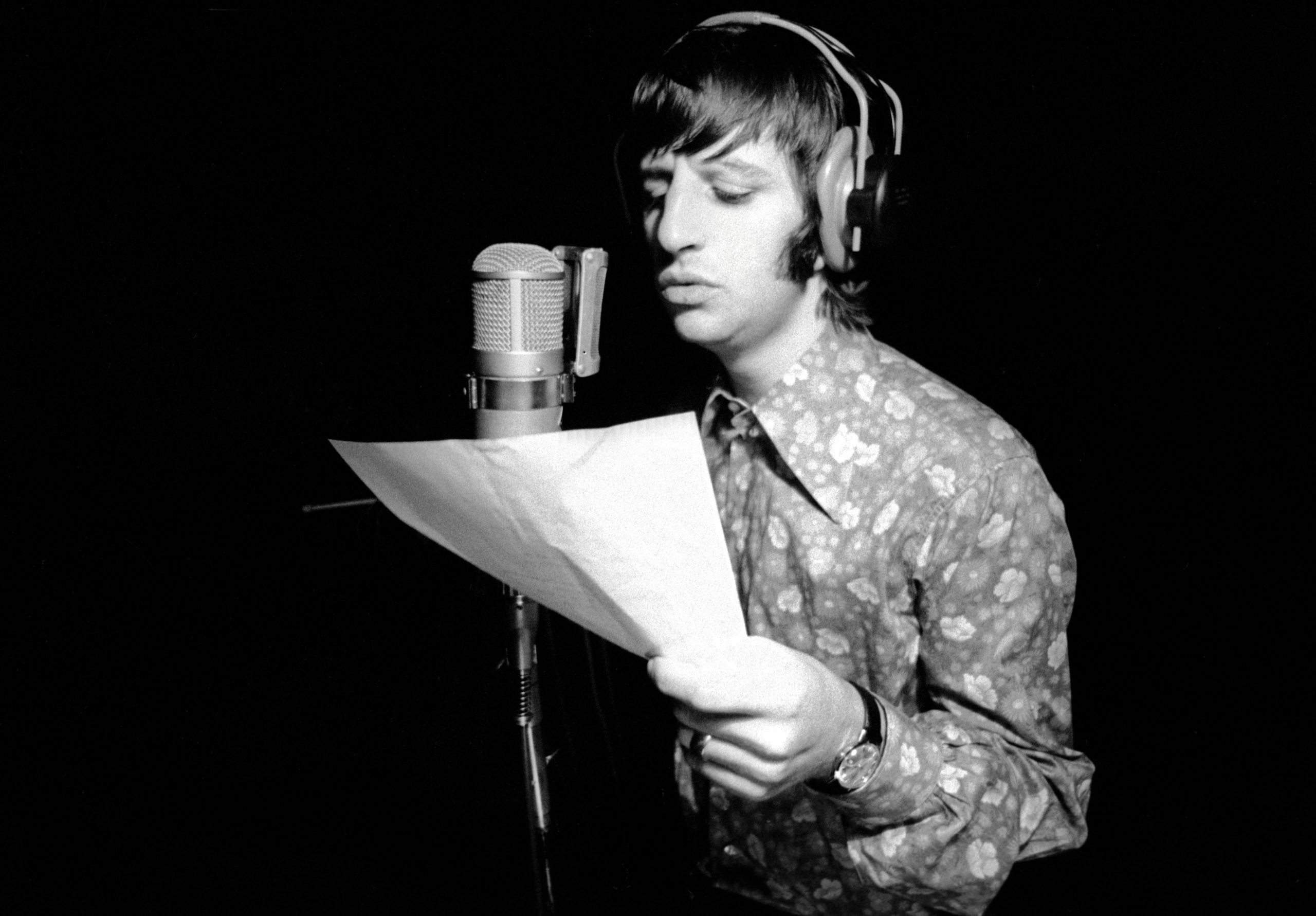

The Beatles would not have been the same without George and Ringo, but they would probably have passed the audition if another guitarist and drummer had played the Quiet One and the Clown. If in doubt, listen to the shows from 1964, when Jimmie Nicol filled in for Ringo, or to Eric Clapton on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” The Beatles would have been nowhere at all, however, without John and Paul. On The White Album, we hear the degree and nature of their collaboration changing in small but powerful ways.

It cannot have helped when John called “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” “granny music s—,” any more than it did the following year when Paul looked Yoko in the eye and sang “Get back to where you once belonged.” But the group’s balance was changed by more than exhaustion or maturation. Entertainers who had become artists, the Beatles had to retain the experimental edge of Sgt. Pepper without losing the melodic appeal that made them the “toppermost of the poppermost.” The harder they worked, the greater the tension between their artistic and commercial objectives. Meanwhile, the pop business, stimulated by the Beatles’ earlier releases, was also pulling in two directions: toward the illusory authenticities of the folky singer-songwriter and toward the hamfisted virtuosity of hard rock.

Only one of the Beatles had the songwriting chops to compete with the warblers of Laurel Canyon. Only one of the Beatles had the dexterity required by hard rock. Both of them were Paul. By 1968, McCartney, like his Tin Pan Alley heroes, could write a song about anything. And he did, producing complex but trivial songs about a sheepdog with low self-esteem (“Martha My Dear”) and a cuckolded cowboy mammal (“Rocky Raccoon”). The chordal and melodic structure of the Bach-derived “Blackbird” are much more sophisticated than John’s riposte, “Julia.” McCartney, the first Beatle to record solo with “Yesterday” in 1964, could accompany himself too. Drumming on “Back in the U.S.S.R.” after Ringo’s walkout, Paul pastiched Ringo so perfectly that none of the critics or fans noticed. On his guitar solo on that track, Paul makes George sound like he has sausages for fingers.

Success was starting to weigh against the band in other ways. The Beatles would never have got as far as they had without Brian and George. But Brian Epstein had died of an overdose in August 1967. In 1968, they took charge of their own affairs and corporatized themselves into one of the most lauded, least productive, and most expensive fiascos in the history of music, Apple Corps Ltd. Now in their late twenties, and possibly the most famous people in the history of the world, “the boys” were no longer willing to take orders from George Martin. When Martin criticized McCartney’s vocal on “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” McCartney snapped back, “Well, you come down and sing it.”

The Beatles’ method of composition remained stable in 1968, but not their method of recording. With early exceptions like “She Loves You,” Lennon and McCartney usually started writing songs separately and finished them together. In the early days, the band had then arranged and rehearsed the songs in the studio with George Martin supervising. When the band acquired home studios and the experimental itch, the songwriter demoed his song, but the rehearsal process remained stable. Almost all of the songs on The White Album were sketched out in this way, in two stages. From February to April 1968, the Beatles went to Rishikesh, India, to meditate with the Maharishi. Between them, Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison wrote about 40 songs. In May 1968, the group recorded rough demos of 27 of them at Harrison’s bungalow in Esher, Surrey. Fifteen of these songs were by John Lennon.

The “Esher Demos” have been widely bootlegged, but students of the Beatles’ methods will appreciate the restored and clear mixes on this rerelease. It is striking how developed the chords, melodies, and lyrics are, and how clear the primary songwriter’s conception is. “Back in the U.S.S.R.” is so complete that you notice when McCartney sings “Man, I had an awful flight” (instead of “a dreadful flight”). The electric experiments of Lennon’s “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide (Except for Me and My Monkey)” are sketched out in frantic acoustic guitar. And “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” is already a Blue Beat stomper.

But when the band went to Abbey Road, they changed their recording process, and not for the first time. Originally, the Beatles had barely used overdubs. By “A Ticket to Ride” (April 1965), they were working up a rhythm track in the studio, recording it quickly to a four-track recorder, then bouncing down tracks to make space for lead vocals and extra instruments and harmonies. Martin’s innovation for Sgt. Pepper, synching two four-track machines to make an eight-track, expanded this palette without changing its method.

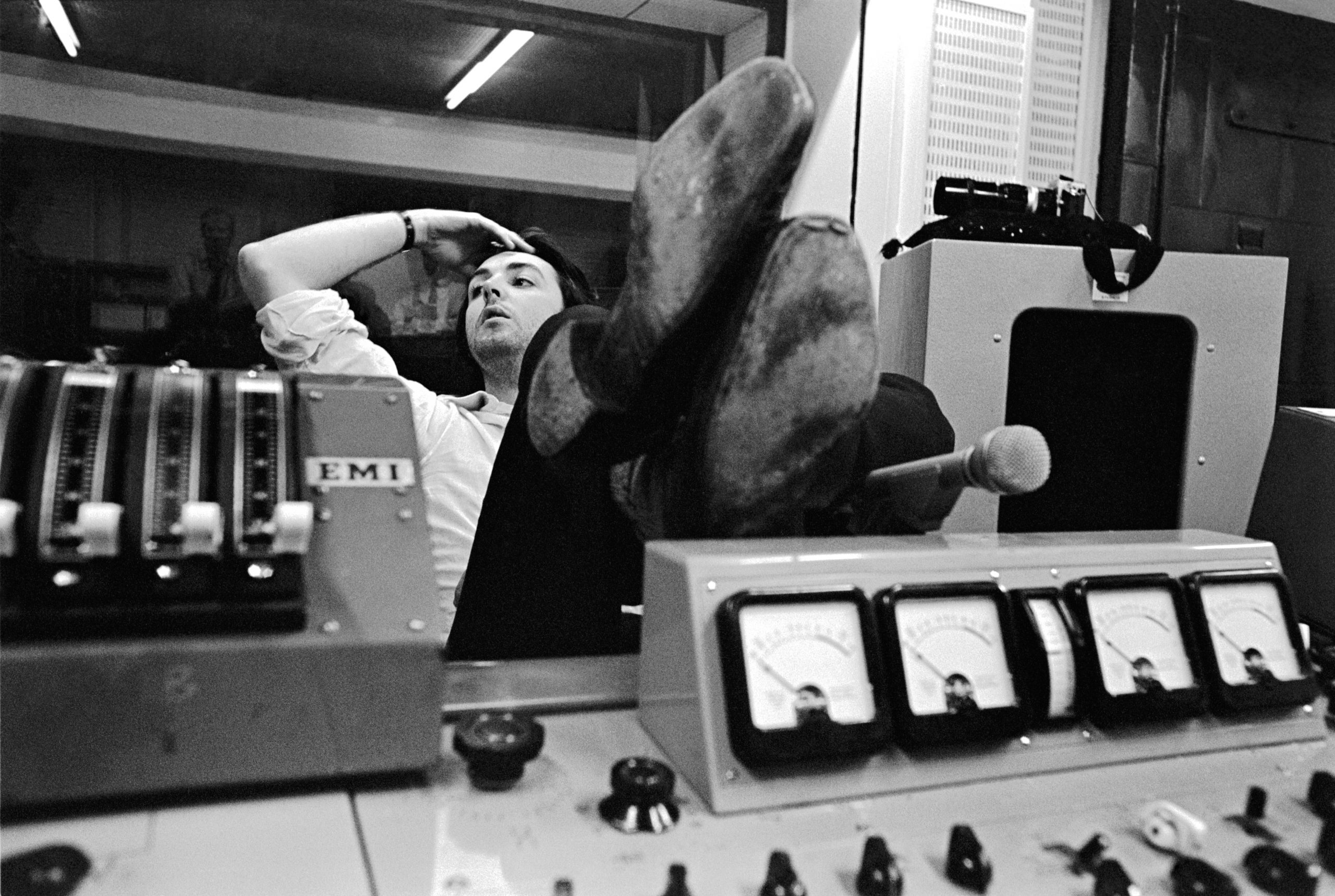

In 1968, with eight-tracks becoming standard in American studios, EMI bought an eight-track recorder for Abbey Road. But the men in white coats had yet to test and install it in the studio. Now the biggest earners in EMI history, the Beatles surreptitiously moved the new machine to Studio 2 and left the tape running. Instead of rehearsing a backing track and putting it to tape when it was fresh, the band now recorded endless jams, then picked through them to find a rhythm track. Often, they couldn’t find one and had to record a fresh rhythm track from scratch. The box set’s two “Sessions” discs make melancholy hearing. Exhausted, the Beatles sound like they are covering themselves.

In 1963, recording their first album in a day, the Beatles had nailed “Twist and Shout” in one take. Six years later, they recorded 102 takes of George Harrison’s “Not Guilty,” only to leave it off The White Album. Meanwhile, as the embellishment and overdubbing grew more complicated, the band spread out into two studios, with George Martin’s aides Geoff Emerick and Chris Thomas at the controls. The result was the polarization of the Lennon-McCartney collaboration into parallel tracks. Instead of complementing each other by refining each other’s compositions, they now wrote antagonistically. The harsher Lennon became, the more sweetly McCartney responded. The result was the kaleidoscopic disorder and variable quality of The White Album.

The White Album should have been John’s rock album, as Sgt. Pepper was Paul’s psychedelic album. But Paul wasn’t zonked on acid in 1968, as John had been in 1967. So a single album of uptight songs that could have brought the aggression and despair of 1968 into focus was blurred by the escapist Pauline indulgences of “Rocky Raccoon,” “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?,” “Martha My Dear,” “Honey Pie,” and the song that shall not be mentioned. As Paul gets his way, so John is allowed “Yer Blues,” “Bungalow Bill,” and “Revolution 9.” And that permits George, whose hit from these sessions, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” lifts its chords from John’s “Dear Prudence,” to spread his vocal and compositional talents too thin.

Though Lennon wrote the strongest songs that year, the collaborative high points of The White Album are often McCartney’s additions to Lennon’s songs. You hear the moral decay of “Sexy Sadie” when the slapback reverb blurs the chromatic descent of McCartney’s piano arpeggios. You hear the desire that drives the exhaustion of “I’m So Tired” when McCartney belts out his harmony on the line “I’d give you everything I’ve got for a little peace of mind.” And it is McCartney who holds every group track together, because his final version of the bassline was often one of the last overdubs. When Harrison, in “Savoy Truffle,” snipes, “We all know Ob-la-di-bla-da, but can you show me where you are?” he’s not referring to McCartney’s musical presence.

“The tensions arising in the world around us—and in our own world—had their effect on our music,” McCartney writes in his introductory note to the book of the box set, “but the moment we sat down to play, all that vanished and the magic circle within a square that was The Beatles was created.” McCartney’s memory doesn’t match those of George Martin and his team. It seems more plausible that the magic happened despite the tensions.

The Beatles were a great live band, and when they worked together, they were still untouchable. You can hear that on The White Album, but you can also hear that the Beatles no longer needed each other in the same ways. The White Album contains superb group performances, but it documents the breaking of a quartet into four individuals. All four members play the live rhythm track on only 16 of the 30 White Album tracks. The dynamics that built the Beatles were starting to break them apart. The group whose second studio album was called With the Beatles could have called its ninth album Against the Beatles.

* * *

Fixing The White Album

The Beatles and George Martin programmed the 93 minutes of The White Album for four sides of vinyl and mixed them so that each side of music was continuous. Printing them onto two CDs alters that. So does listening to the 30 tracks as a single sequence of digital files. So does the crowding of our ears with demos and alternate takes. As ever in the history of pop, technology changes the experience. Digital formats are more flexible. In offering The White Album in totalized form, the heirs to the Beatles’ estate draw our attention to its many flaws and invite us to improve on it by trimming it with a silver hammer.

The White Album is the best Beatles album, but it also contains some of their worst songs. John Lennon knew it when he insulted “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” in the studio. George Martin recognized it too, but the boys overruled his suggestion that they pick the best songs for a single album. George Harrison came to believe that some of the songs would have been better as B-sides, and that “ego” had got in the way. Only Paul, who didn’t want the noise experiment of “Revolution 9” on the record but insisted on “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” claims that no mistakes were made: “It’s the bloody Beatles’ White Album. Shut up!”

Ringo, a master epigrammatist in words as on the skins, got it right. There should have been two single albums, The White Album and The Whiter Album. There often have been, because arguing over which tracks make the cut and whether the cut is even permissible is a common parlor game among Beatles’ fans. And now, in these formats, there will be even more variations.

The rules of the game are that you must program less than 45 minutes of music in two vinyl-style halves. John and Paul may sing two lead vocals in a row, because John does on Tracks 2 and 3 of the original album. George and Ringo must have their own vocal features, whether they deserve them or not. No songs recorded at the sessions but released as singles can be added, so “Lady Madonna,” “The Inner Light,” “Hey Jude,” and “Revolution” are out. Neither can songs from these sessions that appeared on later albums, like “Mean Mr. Mustard,” “Polythene Pam,” and “Across the Universe.” Unreleased studio tracks, Esher demos, and alternate takes may be added as wild cards. Eric Clapton may not be disinvited, because he is fated to steal Pattie Boyd from George, but his solo may be edited.

Per those rules, this is my Right White Album:

1. “Back in the U.S.S.R.” (Paul, 2:44)

2. “Dear Prudence” (John, 3:55)

3. “Glass Onion” (John, 2:18)

4. “Blackbird” (Paul, 2:18)

5. “Sexy Sadie” (John, 3:15)

6. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (George, 4:45)

7. “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” (John, 2:25).

Total: 21:40

Side B:

1. “Helter Skelter” (Paul, 4:30)

2. “Mother Nature’s Son” (Paul, 2:48)

3. “Julia” (John, 2:54)

4. “Savoy Truffle” (George, 2:54)

5. “I’m So Tired” (John, 2:03)

6. “Wild Honey Pie” (Paul: 0:53)

7. “Cry Baby Cry” (John: 3:02)

8. “Goodnight” (Ringo: 3:17)

Total: 22:21