This does not seem the most propitious moment for Adam Fisher’s oral history Valley of Genius to appear. Big Tech, especially its social-media wing, has spent the last year or more simultaneously fighting and pouring gasoline on PR fires. Surely skepticism about the good faith of Silicon Valley companies is at its highest level to date. Why would anyone at this moment want to read an oral history of California’s computing culture told by its self-satisfied and self-congratulatory makers?

There are reasons to do so. Even if you hate Silicon Valley you probably hate it because of the leading role it plays in our everyday lives, and this book is a peek into how that role emerged, according to the people who lived through it. Many of the stories in Valley of Genius have been recorded elsewhere, as long ago as Steven Levy’s groundbreaking Hackers (1984) and Bruce Sterling’s The Hacker Crackdown (1992). But it is useful and interesting to have most of the old anecdotes gathered between two covers, because from them a single overarching story emerges. It is, financially speaking, a story of rise and rise, though ethically speaking one of decline and fall.

Edward Gibbon, whose Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is the progenitor of the genre, had a simpler tale to tell, because he could show Rome declining in power as its ethical foundations crumbled. The moralistic among us can take comfort in such a narrative. It is harder to find satisfaction in reading about people whose moral decline is accompanied by ever-rising bank balances, whether you think the wealth caused the moral collapse or vice versa. But Gibbon’s narrative and Fisher’s have this in common: They trace changes that happened, in one of Gibbon’s favorite words, “insensibly.” The paths taken by Rome and Silicon Valley were not marked primarily by crises, by clearly decisive moments—though there are a few of those—but rather by the long, slow transformation of institutions from one kind of thing into a very different kind of thing.

It’s not clear that Adam Fisher understands the story he has told in quite the same way I do. He was raised in Silicon Valley and got interested in computers at an early age, like many of the people we hear from throughout the book, and he says right up front in the preface that, while he himself appears but rarely in the book (mainly in brief introductions to each chapter), he endorses the outlook of his protagonists:

I am not especially fond of Marxist cultural critique, but this kind of thing begs for it. Of course the stories were never about money! Of course the people who have become wealthy beyond the imaginings of mere mortals and are rapidly transforming the whole city of San Francisco into a playground for themselves and their fellow megarich think of themselves as dragon slayers instead of Daddy Warbuckses in antimicrobial T-shirts and $300 jeans! Such delusions are among the first and most lasting symptoms of affluenza.

And since this is an oral history, told wholly by participants, the reader should not be surprised to find the gee-whiz triumphalism of Fisher’s preface echoed throughout the book. To be sure, critical voices are occasionally heard, but their impact is consistently muted. For instance, a few aged persons like me might remember the protracted legal struggles at the turn of this millennium between Napster—the first really successful service for sharing digital recordings of copyrighted music—and the Recording Industry Association of America. One of the chapters of Valley of Genius deals extensively with this conflict, and near the end Fisher quotes Hilary Rosen, then-CEO of the RIAA: “Napster was very prescient, but everyone was greedy.”

Rosen is immediately followed by Sean Parker, cofounder of Napster (and later the first president of Facebook):

And: End of chapter. Parker’s assertion of his own moral purity therefore goes unquestioned, and we are clearly meant to set the book down for a moment to shed a brief tear for the unmerited suffering of those, like Parker, who dedicated themselves wholly to public service without even the briefest thought of remuneration. Truly, there were giants on the earth in those days.

But here cue Don Henley: “This is the end, this is the end of the innocence.” For, though I have said that Fisher’s story has few turning points, the collapse of Napster seems to be one of them. For Fisher, I think, it marks the end of the real hacker era, the era in which programmers could without irony and without mental-moral gymnastics see themselves as Sticking It To The Man—as ushering in what Parker calls “a social revolution, a cultural revolution.” The defeat of Napster in the courts and its subsequent collapse were just part of the bursting of the first dot-com bubble, and the chapter immediately following the one on Napster deals with that catastrophe. The tagline for that chapter comes, interestingly enough, from Sean Parker. The full quotation from which Fisher draws the tagline comes in a passage where Fisher is quoting people on how much more pleasurable life in the Bay Area became after the dot-com bust, because quite suddenly the highways became easily navigable and you could always get a table at the restaurant of your choice. If, that is, you were one of the lucky ones to keep your job. Here’s Parker’s line: “Only the cockroaches survive, and you’re one of the cockroaches.”

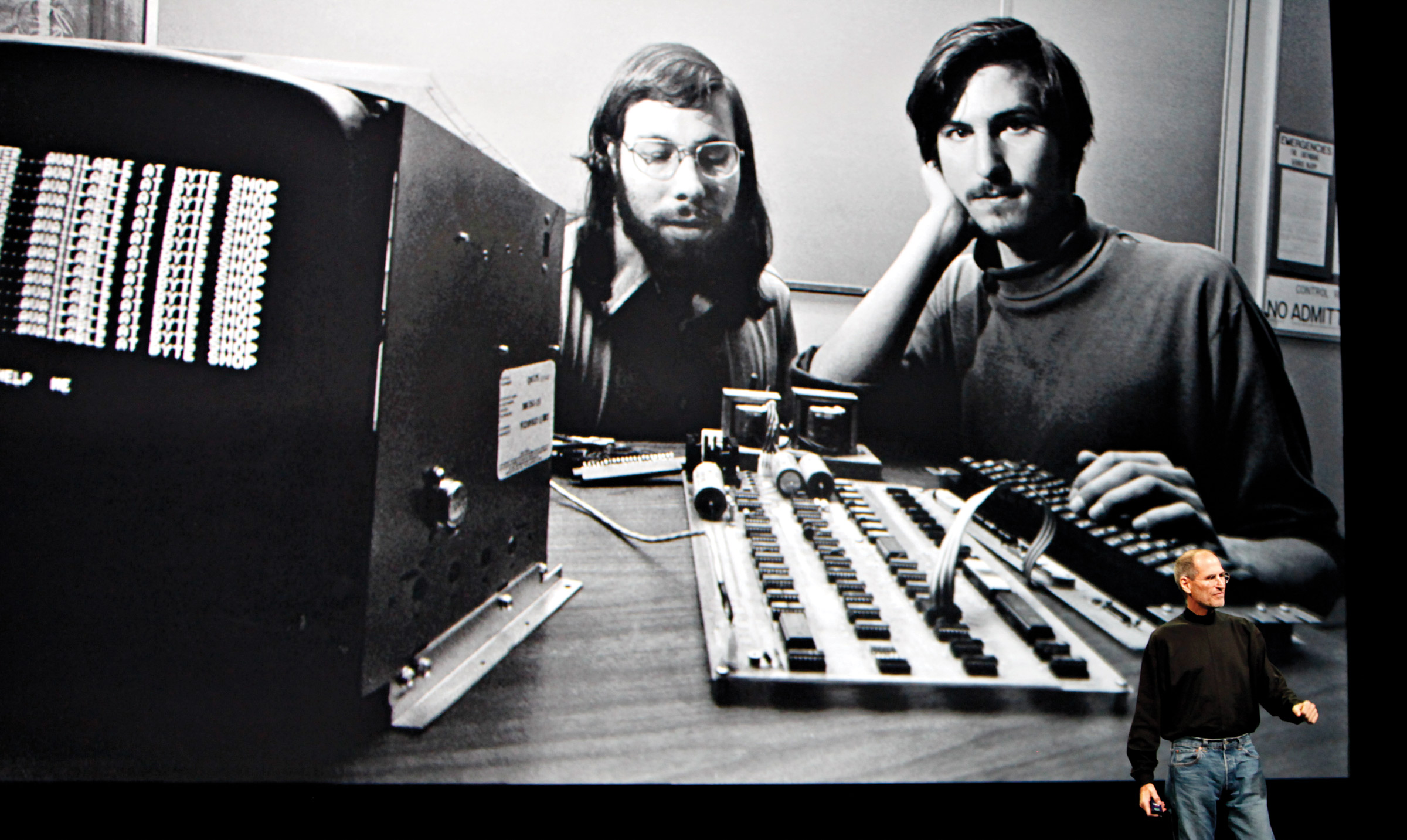

Valley of Genius is a tale told by the cockroaches, full of sound and fury, yes, but signifying quite a lot—especially in the book’s second, post-Napster, half. Because look at what follows: three chapters on the skyrocketing fortunes of Apple after the return of Steve Jobs, one on Google, one on Facebook, one on Twitter. I can’t say I’m displeased to see a little of my cynicism creep into Fisher’s narrative at this point. In the chapter on Facebook we find this passage:

Ruchi Sanghvi: “Domination” was a big mantra of Facebook back in the day.

Max Kelly: I remember company meetings where we were chanting “dominate.”

Ezra Callahan: We had company parties all the time, and for a period in 2005, all Mark’s toasts at the company parties would end with “Domination!”

Mark Zuckerberg: Domination!!

There are two further quotations from Mark Zuckerberg in that chapter, which I shall now reproduce in full. The first is “Domination!!!” The second is “Domination!!!!”

Similarly, the chapter on Twitter contains some sober assessments of that platform. Zuckerberg remarks of Twitter’s founders, with a wit that I didn’t know he possessed, “It’s as if they drove a clown car into a gold mine—and fell in.” The journalist Nick Bilton speaks for me when he says, “I think we’ll look back at Twitter in ten, twenty, thirty years . . . and say, ‘Well, that didn’t work out so well, did it?’ ” And at the conclusion of that chapter a voice from outside Silicon Valley emerges and, um, dominates: @realDonaldTrump.

So, yes, decline and fall. Some people who have been involved with Silicon Valley since its humble beginnings have been railing against the transformation all along, and Fisher allows us to hear from a couple of those Jeremiahs, at least occasionally. Interestingly, they tend to be people who meet a rather stricter definition of “genius” than the one that welcomes Sean Parker and Mark Zuckerberg into the club. One is Alan Kay, the closest thing we have to an actual inventor of the graphical user interface, who was present at the creation and laments the failures of imagination that, ironically enough, led to economic domi- . . . ascendancy. Another is Jaron Lanier, the chief pioneer of virtual reality computing, who has been condemning the wrong turns of his profession for more than a decade, most notably in such books as You Are Not a Gadget and Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. Fisher quotes him thus:

To his credit, Fisher lets us hear Lanier’s critique on at least a few occasions. But it’s not the note he wants to end on.

In an epilogue on the likely future of Silicon Valley the major voice is the eminent futurist Kevin Kelly, who says, “When I think of the future of Silicon Valley I see it as still being the center of the universe”—which is not exactly what T. S. Eliot meant when he wrote of “the still point of the turning world.” Or was it? Kelly has written that “we have a moral obligation to increase the power and presence of technology in the world.” Why? Because through remaking the self via technology we are bringing into being the Technium, which is also God: “I think of God as the intelligence of mind that is increasing the complexity of the universe.” The priests of Silicon Valley say, Let us give thanks to the Technium our God. And the response written for us in the prayer book is It is meet and right so to do.

Many, perhaps most, of the readers of Valley of Genius will share this belief in the inevitable victory of our genius technocratic overlords. Some of them even welcome it. As for me, when I got to the end of the book, I thought, “Well, that was fascinating! Now let me just go take a long soak in a big tub of disinfectant.”