When Sir Gawain and the Green Knight first appeared in print, in 1839, its wintry world of Christian revelry, chivalric honor, and Arthurian romance had long since vanished. Indeed, that world, or rather, medieval romantic literature as a whole, was antiquated even at the time the poem was written, somewhere in northwest England, in the late 14th century. In that same period, Geoffrey Chaucer was scribbling away down south, inventing the principles of modern English versecraft and casting a comic and condescending eye back on the old tales of Arthur. The age of chivalry was dead.

And yet, Gawain is not just a belated instance of medieval romance. Although the anonymous poet begins by insisting he shall tell the tale “to you right away, as I heard it in the court / Being told,” and closes by claiming that “the books of British history bear witness to” what he has reported, in story and form, Gawain is a thing of striking originality and poetic genius. Although it seems to have had a small and isolated audience at the time of its writing, it has long since come to be recognized as the crown jewel of medieval romance and, second only perhaps to Chaucer, the polished masterpiece of Middle English. As is the case with Chaucer’s poetry, Gawain at once looks back to an age that appears at times enchanted, at others merely strange, and ahead to the English poetic tradition as it came to maturity.

For those interested chiefly in the exoticism of the poem’s world and style, Simon Armitage (in 2007) and others have provided translations of its obscure, brute, snarling, and monosyllabic dialect into modern English. For those who wish to get a sense of the poem as standing in continuity with our intellectual and linguistic world, however, John Ridland’s new translation will become the standard. I have never before seen the journeyman work of close translation pay such great artistic dividends. Ridland has pulled off a startling success that brings new life to an old poem; like the poem in its original context, Ridland’s translation offers significant lessons for us, now, about both poetic form and the moral form of our lives.

The Gawain poet gathered elements from a number of earlier legends in order to craft a finely wrought story of magic, charm, and wit that is also rife with moral gravitas. After a portentous preface that sets the poem’s action in the context of the history of the Roman and Christian West, the tale begins during the Yuletide festivals in King Arthur’s court. Amid the revels comes a giant but handsome man, green-clad and green of skin, carrying a large green axe. He challenges the court to play “a little Christmas game”: Someone may chop his head off with the axe, so long as, a year and a day from that night, he may return the favor.

Amid a shocked but intrigued court, young Gawain takes the bet. He swings, the head rolls, blood spews. But that is not the end. The knight’s body picks up the head and leaves, calling as it goes a reminder to Gawain to meet him in a year at “the Green Chapel.” This is all the best Christmas present King Arthur could imagine!

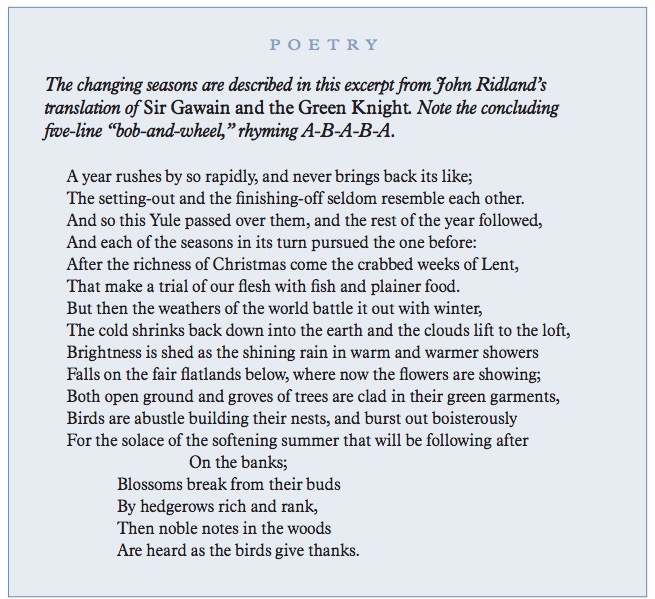

The year passes; the poet depicts the cycle of seasons with vivid beauty. (See excerpt.) When Christmas comes, Gawain sets off and fights innumerable monsters before arriving—cold, alone, and longing to hear Mass—at the castle of a mysterious lord. He is welcomed warmly. The lord’s beautiful wife and a squat, hideous old hag join him at prayer. In the hall, Gawain and the lord and his company make Christmas merry.

Then comes another Christmas “game” of sorts. The lord goes hunting each of the next three days, promising to give all he catches to his guest, while Gawain is left abed to recover from his journey. Gawain promises, in return, to give to the lord whatever he “catches” at home. The poem’s most brilliant achievement of narration then unfolds as the hunting party’s pursuits of female deer, a prickly and armored wild boar, and at last a fox are paralleled with the lady of the castle’s pursuit of Gawain.

Each morning, the lady crawls into Gawain’s bed, offering him her playful love talk and, soon, her body. All Gawain will accept, initially, is a kiss; each night, he gives the kisses to the lord, in accord with their bargain. The visceral realism of detail regarding the hunt and the playful courtly banter of the flirtation conjure up the precisions of a world while also conveying a sense of life as having a sacramental and symbolic form, wherein martial courage and masculine courtesy mirror and interpret one another for our benefit.

But on the third day, the lady offers Gawain not only kisses but a green sash. He accepts it, not because it is valuable, but because she has said it will protect him from bodily harm. When the lord returns that night, Gawain gives the kiss but keeps the sash tucked away.

He leaves the castle on the cold morning of his fate and arrives at the Green Chapel. The knight appears. Gawain bows and the axe is raised. The green knight brings it down once, twice, without contact. Gawain flinches but swears in anger he will not again and that the knight should get this over with. At last, the blade falls—but delivers just a cut across the back of the neck.

Gawain has been spared. Why? The green knight, we now learn, is the lord of the castle, transformed by King Arthur’s wicked half-sister, the enchantress Morgan le Fay—who, we now also learn, is the old hag in the castle. The whole “game” has been a plot by vengeful Morgan to “startle” Queen Guinevere to death.

That cannot be the meaning of the story, however. You endured the trials of chastity and honor with my wife, the lord tells Gawain, except in your keeping back the sash. For this alone he has been cut. Gawain wears a “pentangle” on his shield, an emblem of integrity and courage without end. Living under the promise of certain death and through the temptations of the “green” yearnings of the flesh, he has proven himself a knight indeed—except for one act of cowardice that, like original sin itself, may be forgiven but never forgotten. Gawain’s trial is that of every Christian soul, where joy and fear, heroic virtue and creaturely fallibility mingle in unexpected ways.

The poem was originally composed in loose alliterative lines, the number of stresses per line and number of lines per stanza varying considerably. In this, the poem drew on the fading traditional practices of Old English. Each stanza culminates, however, in a five-line “bob-and-wheel” whose use of meter and rhyme anticipates the emergence of the iambic line and the rhymed stanza that would soon become the essential form of English verse.

Most translators have either abandoned the form altogether or tried to replicate its alliterative movement in hopes of conveying its harsh, Germanic energy. Ridland, in contrast, renders the poem in loose iambic heptameter, thereby giving us a form that sounds both native and natural to our ear. He also introduces sporadic and spritely alliteration to preserve a hint of the poem’s exotic roughness.

Gawain’s Middle English dialect is not only rough but dense. Ridland set himself the goal of accounting for every word of the original and keeping his translation accurate, line for line. Although I found a handful of what are either liberties or errors, on the whole he succeeds. His meter is looser and more irregular than I would have it, and yet he has given us the first translation of the poem that achieves close literalness of meaning, colloquial clarity, and rich prosodic beauty.

Without collapsing its historical distance from our age, Ridland has brought the poem fully into our literary tradition. The Gawain poet himself, who so ingeniously wove the Christmas and chastity challenge narratives into a sinuous and significant whole; who captured a world rich and orderly with sacramental symbols and peppered with a thrilling realism of detail; and who, even so, introduced, quite incoherently and at the last moment, the plotting of Morgan le Fay could hardly have achieved a more perfect success.

James Matthew Wilson teaches humanities at Villanova. His most recent book is The Vision of the Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in the Western Tradition.