Not long after the Crash of ’29, when such zaniness as goldfish-swallowing and flagpole-sitting could still distract a desperate nation, 35-year-old Plennie L. Wingo (his real name) had an idea. His restaurant in Abilene, Texas, had gone under. So he embarked on an attention-grabbing and, he hoped, moneymaking stunt of his own. He would walk around the world backward.

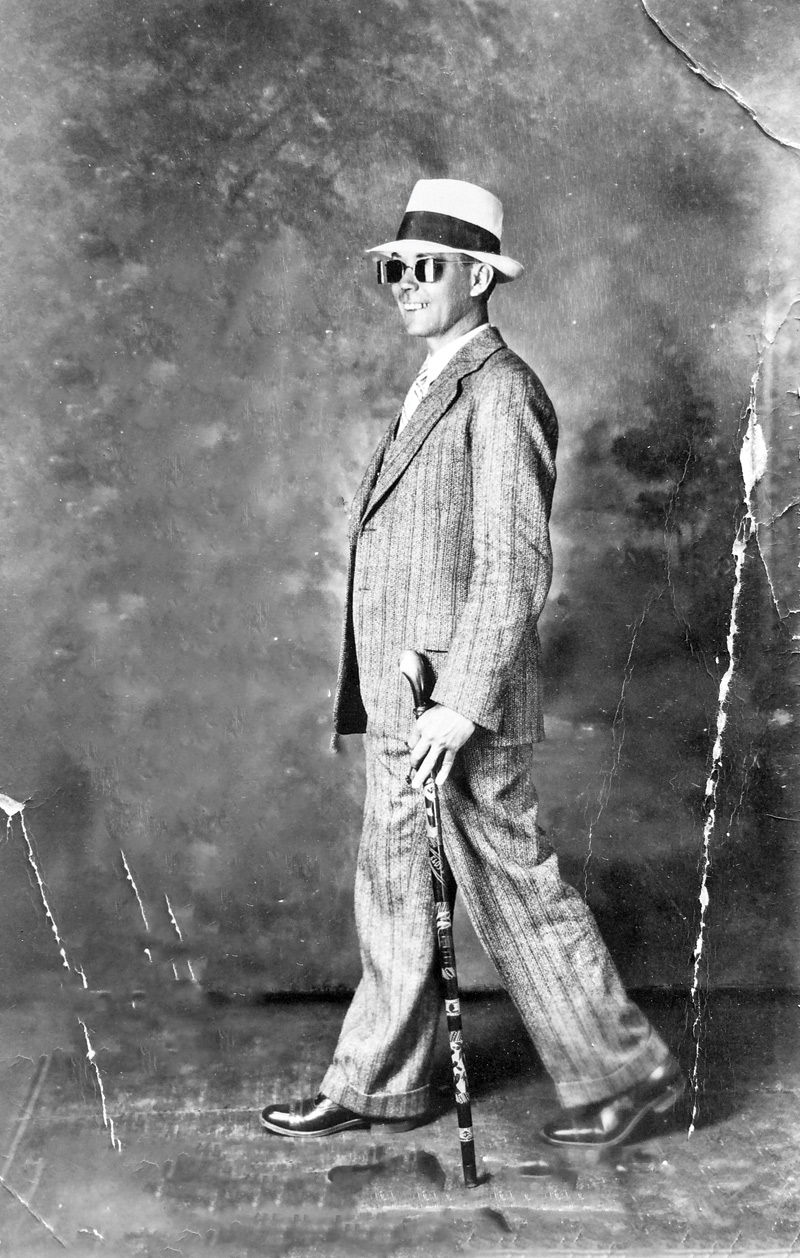

Wingo figured he would cash in with endorsements and pledges from local businesses and chambers of commerce. He would sell postcards of himself. The press and newsreel publicity would be priceless! He would write a book! Equipped only with a cane and a pair of sunglasses that sported small side mirrors—created for use by motorcyclists and sports-car drivers—Wingo set out east from Fort Worth on April 15, 1931.

He ultimately didn’t trot the whole globe. He made it to Boston and then sailed for Hamburg. But after retrograding through Central and Eastern Europe, he was collared at the Turkish border. The police, the Chicago Tribune reported, “couldn’t decide whether he was coming or going.” Following his release from jail, the U.S. consul convinced him to abandon his kooky scheme. Not only was Wingo becoming an annoyance and even a threat to public safety, he was entering some pretty dangerous territory.

So Wingo came home and settled for walking with his rearview specs across his native land. Starting from Santa Monica on August 13, 1932, he returned to Fort Worth two-and-a-half months later. Altogether, writes author Ben Montgomery in his new book The Man Who Walked Backward, Wingo had backwalked for “one year, six months, nine days, four hours, and twelve minutes,” logging more than 5,000 miles (or more than 7,000, depending on your source). In the end he made all of four dollars, wore out 12 pairs of shoes and, while on the road, was sued by his wife for divorce.

In this odd book about an odd little (5-foot-5) man, Montgomery, a veteran of the Tampa Bay Times, doesn’t skimp on trivia and anecdotage. Wingo, it turns out, intended only to walk backward between towns. By the time he got through 16 states (and Washington, D.C.), his musculature had become so reversed that his calves were at the front of his legs. In Lemont, Illinois, he amused onlookers by eating an entire meal in reverse, beginning with his dessert and finishing with his soup. Setting out for Hamburg, Wingo walked backward on the gangplank; in Germany, he backwalked a dozen miles or so in the wrong direction.

There’s memorable drama, too. In Baxter Springs, Kansas, a jealous husband threatened to kill the weird ex-restaurateur merely for talking with his wife. Wingo himself beat the hell out of a chiseler who failed to pay him for walking backward along the top ledge of an Art Deco building in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He spent three weeks in a hospital after breaking his ankle near Canton, Ohio. In Pittsburgh, a cop told a frightened Wingo that he was ticketing him for “mopery in the second degree”—only to reveal, laughing, that he just wanted to have some fun with him. Wingo laughed along.

This is welcome color in a sloppy book. Montgomery’s introduction stresses that his documentation is accurate. I believe him. But the book’s subtitle is An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression, and Wingo simply doesn’t do a lot of dreaming. Ultimately he’s just a guy with a gimmick. “With the whole world going backwards,” our hero reflects in later life, “maybe the only way to see it was to turn around.” That’s as deep as his introspection gets.

If Wingo ever found a greater significance to his antics, Montgomery only occasionally divines it. More than once, Wingo entered towns that squinted at him as a dubious outsider, with suspicions fueled by financial jitters, recent crimes, simmering racial tensions, and similar unpleasantness. Happily, he also found kind strangers who fed him, cheered him on, and even took him in.

But Montgomery rarely analyzes and integrates this material into any grand narrative. Instead, he unleashes torrents of historical recitation. Hence, when Wingo journeys through the Great Plains, we get about 2,880 words on regional topography and wildlife, broken Indian treaties and massacres, and the awfulness of the Dust Bowl. Montgomery chokes you with not especially fascinating statistics (did you know that when Wingo arrived in Joplin, Missouri, it had 7,468 telephones, 42 churches, and a library filled with 56,708 books?). During these asides, Wingo virtually disappears.

And unlike its subject’s footsteps, the book is badly balanced. Montgomery takes more than 200 pages to set down Wingo’s personal story and his odyssey until he reaches Germany. Yet he devotes only a dozen or so pages to Wingo’s trek through Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece, and a mere nine to his 1,450-mile California-to-Texas leg. Perhaps this was unavoidable—maybe there just aren’t many good documentary sources describing those parts of Wingo’s trip—but the lopsidedness is striking.

Montgomery’s attempts at philosophizing (“It’s funny what a fella thinks about when he’s alone”) are as graceless as his rat-a-tat-tat sentences (“Prices dropped. Dropped fast. Dropped hard. Dropped vertically.”). Sometimes he sins simultaneously (“Cities fall. Empires fade. History favors the persistent.”). And oh, the clichés! “Without missing a beat,” “vim and vigor,” “between a rock and a hard place,” “the jig was up,” “old hat,” “the college try,” “fuel for the fire,” and “hand over fist” are typical.

Plennie Wingo quickly became a footnote in the memory of his and later generations. More than 30 years after his outlandish gambit he finally published his book, inaccurately titled Around the World Backwards, to little notice. He appeared on The Tonight Show in 1976 and that same year made $500 by walking 400 miles backward to end up at the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! museum in Santa Monica. In 1993, he died in poverty and obscurity at the age of 98 at his home in Wichita Falls. It’s not clear if he was carried out feet first.