Maybe you saw the recent movie Don’t Look Up, with the tagline: “Based on real events … that haven’t happened — yet.”

Or maybe you’ve seen the competing 1998 movies Deep Impact or Armageddon based on the same premise: A large celestial object is on a collision course with Earth and will result in a mass extinction event on the scale of the one that is believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

In the Hollywood versions, manned spacecraft and nuclear weapons are required to intercept the extraterrestrial object and knock it off its deadly trajectory. But in the real world, a small unmanned spacecraft need only nudge a potentially threatening asteroid slightly off course to prevent potential disaster.

Later this month, NASA will conduct the world’s first test of a planetary defense system with a spacecraft dubbed “DART,” short for Double Asteroid Redirection Test.

The idea is to test the theory that an asteroid’s motion in space can be deflected ever-so-slightly through “kinetic impact” — in other words, by sending a spacecraft crashing into it.

For the test, NASA has picked a target asteroid some 93 million miles away that poses no threat to Earth and never will.

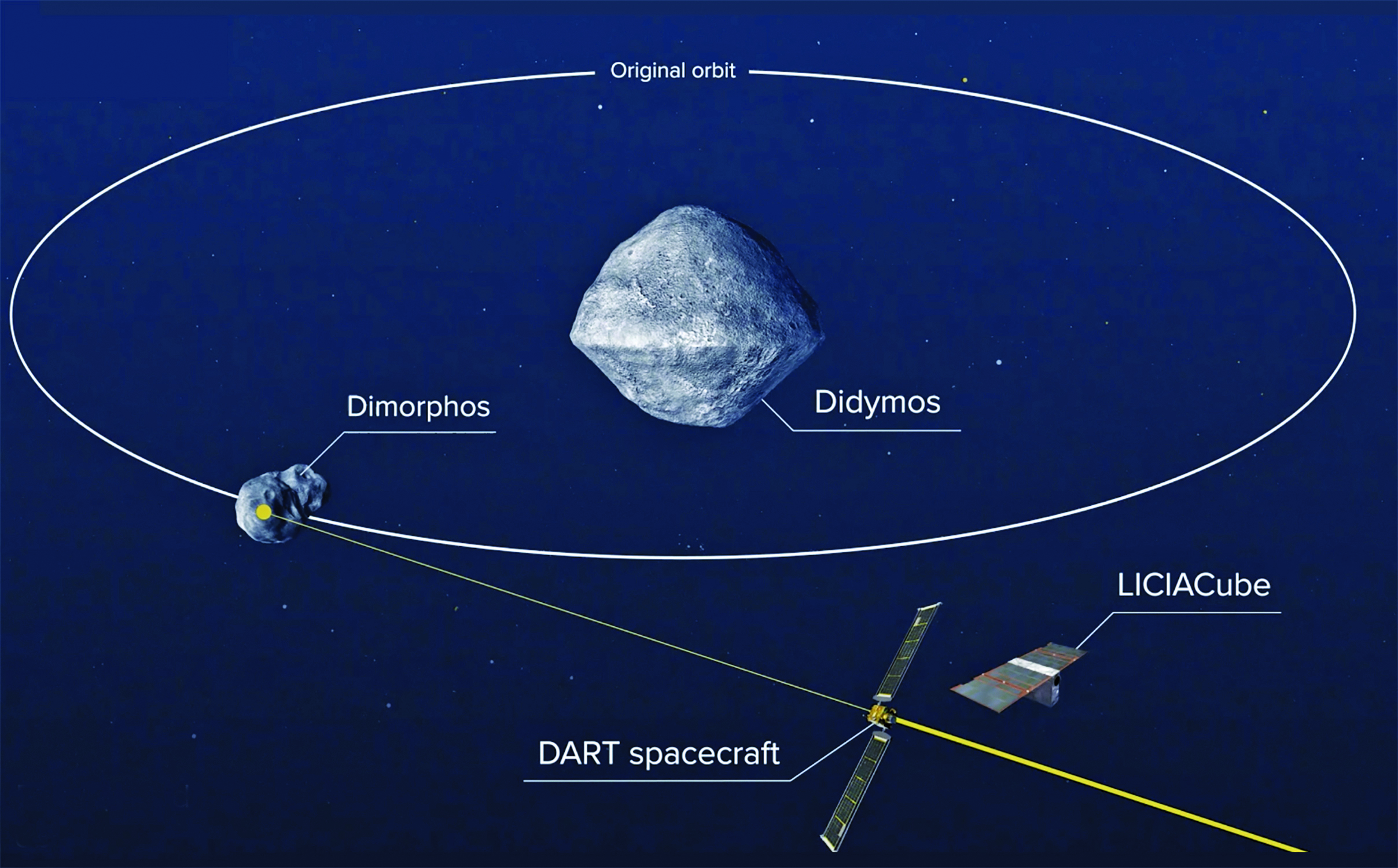

The DART spacecraft will arrive Sept. 26 at the half-mile-wide “double” asteroid Didymos, which, like the Earth, is orbiting the sun. And also, like the Earth, it has a small moon, Dimorphos, which is about the size of a football stadium, orbiting it.

“We are perfectly safe from this asteroid, and nothing that we’re going to do to it will increase the hazard,” said Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer. “By conducting this test against the moon, just changing the orbit of the moon, we don’t change the orbit of the primary body around the sun, so it doesn’t really change its orbit relative to the Earth.”

The plan is to send the DART spacecraft, which is about the size of a car, slamming into the smaller, stadium-sized orbiting moonlet, Dimorphos, at 16,000 miles per hour, thereby altering its speed around the bigger asteroid from about 12 hours to 11 hours, 45 minutes.

If NASA can slow the orbit by as little as 7 minutes, it would be enough to make a hypothetical asteroid on a collision course miss.

Now the good news.

“There is nothing to worry about for certainly many millennia into the future about asteroids’ size of the one that is thought to lead to the demise of the dinosaurs. That was an asteroid estimated to be about 6 miles across,” Johnson said. “We know of any asteroid of that size that enters the inner solar system,” he said, adding there are none that threaten Earth or will for thousands of years.

So, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office is looking to catalog near-Earth objects as small as 140 meters because, while they don’t qualify as “planet-killers,” they could, in theory, devastate a statewide region, creating a natural disaster on a massive scale.

Again, the news is good.

NASA says there are no known asteroids that will pose any significant risk to Earth for at least the next 100 years.

“We don’t have anything currently in our catalog that has an impact probability of any significance,” Johnson said. “By that, I mean the probabilities are far less than one in a million, but the flip side of that is that we don’t know everything that’s out there.”

NASA believes it’s found only 40% of the near-Earth objects in the 140-to-160-meter size range.

Nevertheless, the odds of what’s considered to be the highest-risk known asteroid to hit the Earth are calculated at less than two-tenths of a percent, and that’s not until the year 2185.

Another asteroid on NASA’s watch list, called Bennu, has an estimated 1-in-2,700 chance of hitting Earth sometime between 2175 and 2195.

And while the movies make it seem like a complex mission to deflect an asteroid, in reality, it’s technologically relatively simple and doesn’t require landing on the surface or the use of nuclear weapons.

“Currently, an asteroid impact is the only natural disaster we might be able to prevent,” NASA says on its website. “After all, we’d only need to nudge an asteroid’s orbit enough to make it either seven minutes early or seven minutes late in its intersection with Earth’s orbit … if an asteroid arrives seven minutes early or late — it’ll miss us completely.”

While the signal from the DART spacecraft will go dark as soon as it hits the tiny moon, viewers on Earth will be able to see the impact thanks to the LICIACube, a small auxiliary craft made by the Italian Space Agency that has separated from the DART and is trailing behind it to provide imagery after the collision.

NASA will provide live coverage of the impact on its television and streaming channel, beginning at 6 p.m. EDT on Sept. 26, with impact scheduled for 7:15 p.m. EDT.

It will take a few weeks for NASA to compute the new orbit by observing the light curve of the moonlet as it passes behind the main asteroid.

Only then will we know if the world has a planetary defense capable of saving humanity from a natural disaster from space.

Jamie McIntyre is the Washington Examiner’s senior writer on defense and national security. His morning newsletter, “Jamie McIntyre’s Daily on Defense,” is free and available by email subscription at dailyondefense.com.