A man recently

killed his friend for picking up the check at an Istanbul restaurant. Anyone who’s familiar with the sport of Middle East check wrestling cannot be surprised. Dining companions can go at it for half an hour arguing over who gets to pay the check and thereby prove one’s magnificent munificence. I dread to think how this murder has raised the stakes in Beirut, home to some of the region’s most energetic check wrestlers: Now, if you don’t shoot your friend, his wife, and kids, you’re just pretending to want to pay the check. If you’re not willing to kill his entire clan and everyone else in the village, you just don’t want it enough.

It would not be the strangest thing French chef Olivier Gougeon has seen in a Middle East restaurant. Olivier and his Lebanese-American wife Marie-Hélène Moawad are owners of the Villa Clara, a hotel and restaurant in Beirut. It’s a beautiful old mansion in the Mar Mikhael neighborhood, the city’s liveliest and, given regional dynamics, maybe last nightlife spot. Olivier learned how to restore a house on the job and Marie-Hélène, who has a doctorate in business and marketing, decorated it with contemporary art by Lebanese and Syrian artists. Olivier and Marie-Hélène have two children, Clara, whom the hotel is named after, and her younger brother, Patrick. Villa Clara is a wonderful place, with winter mornings by the fire and fresh-baked bread for breakfast, but it’s not until evening that things really kick into action. The dining room is nearly always full, with Lebanese celebrities of one sort or another—politics, art, media—as well as foreigners, like the European ambassadors who convened a private party when I was there in late January.

Beirut is a city of excellent food, but Olivier has been the best chef in town since he first came here nearly twenty years ago to do his French national service. “I told them I wanted to be sent to a country that had its own wine industry,” says Olivier. “And then they say, ‘ok, you’re going to Lebanon.'” Lebanon indeed has a terrific wine industry. As my old friend the Lebanese wine expert Michael Karam told me many years ago, wines “are arguably the country’s only legal world-class export.” Olivier’s concern was the vintage of Lebanese chaos. “You know when we were kids that’s how we described something that’s totally messed up, ‘like Beirut,’ and now I’m sent to cook for the French ambassador to Lebanon.”

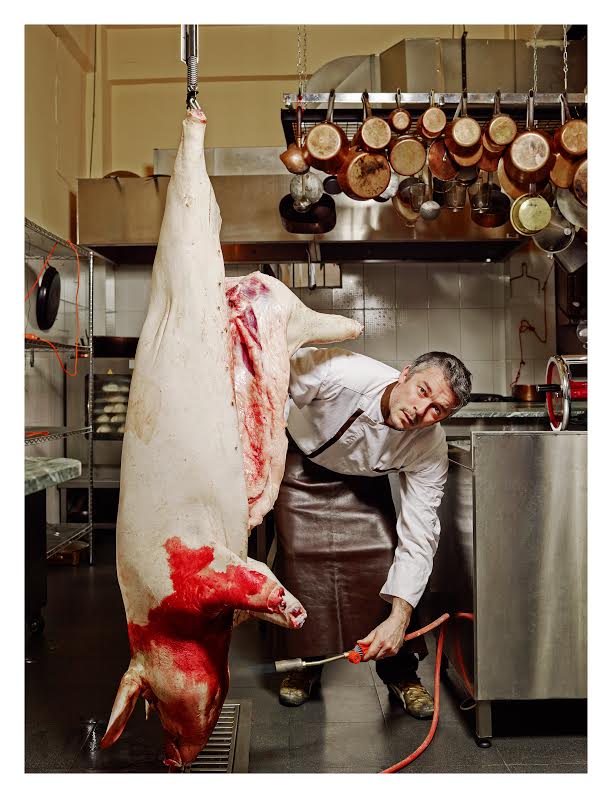

All the Lebanese politicians were happy to be summoned by the French envoy—if it meant being served one of Olivier’s dishes. He’s famous in town for making his own charcuterie—a life-size painting of him holding a big knife and a butchered pig hangs in the kitchen where it doubtless inspires lazy wait-staff. However, his signature dish is steak tartare, which he prepares at your table. The Chef, as Marie-Hélène refers to her husband, has a flair for the dramatic and turns steak tartare into a performance, a theatre piece, where he rolls out a long wooden table and starts carving the raw meat and adding ingredients, capers, onions, eggs, etc. The real drama is the knife work, furiously slashing and scissoring the raw meat for ten minutes or so until it’s ready.

I ask him where he learned to use the knives like that. “The first restaurant I worked at in France, there was a Japanese guy there starting out just like me,” says Olivier. “His mother sent him away from Japan because he was getting in trouble. He told the boss, ‘you know, Japanese people are very nice, right, quiet and get along with everyone?’ And the boss nods his head and says, yes, sure. And he says ‘not me, I’m not nice.’ Then I noticed he had these tattoos all over his arms. That’s how I learned my knife work, from a guy in the Yakuza. He was an excellent chef.”

Olivier once sailed his small boat from France to Lebanon, a trip that took him three months with stops in nearly every port along the way. Sailing the Mediterranean clarified aspects of The Odyssey for him. “When things go bad you don’t have time to be scared,” he says. “You just have to get done what you need to do, and when you can finally sleep you are so exhausted you might have hallucinations. Once I was sailing with another guy and we found out we had the same hallucination after a storm. It’s the same sort of thing that sailors have imagined always. It’s very powerful. I understand why Odysseus had to be lashed to the mast.”

While some gods had it out for the wily Odysseus, others favored him. If Olivier has a deity watching his back, it’s the god of raw beef, since that’s played such a big part in his life. That was the first meal that Marie-Hélène’s mother made for him, just as they were starting to date. “I was so embarrassed that he kept eating so much kibbeh nayeh,” says Marie-Hélène, referring to the Lebanese version of steak tartare. “It made your mother happy,” Olivier remembers. More importantly, says Marie-Hélène, his frank pleasure in consuming as much raw beef as was offered convinced her father that Olivier was an honest guy. “That was the most important thing to my father,” she says. “Yes,” says Olivier, “and he knows very quickly if someone is being honest because he was once head of Lebanon’s intelligence service.”

Beirut is in the middle of several crises right now, including the Syrian war and the 2 million refugees it’s sent here, and so the city has a harder edge than usual, harder than I’ve ever seen. The garbage hasn’t been collected in nearly a year now and poses a real health risk, as if the Lebanese need yet another threat to the their lives and sanity. The city’s getting smaller it seems, or the places that embody the reasons why people still love this troubled city are getting fewer. And yet Villa Clara, Marie-Hélène and Olivier, still project the romance and glamor, the kind of values that represent Beirut at its best—stylish, multilingual, multicultural, and warm.

Ok, I ask, what is the strangest thing you’ve seen at a restaurant in the Middle East? “I wanted to raise my own cow,” says Olivier, tending the fire. “So I checked in on the cow regularly, even named her. One day, I go to the farm and see her and tell the caretaker that she’s ready. I tell him to take the cow to the restaurant I had in Byblos—a fantastic steak place. It’s about three hours before we open and here comes the farmer with the cow—on a rope. I ask him, ‘hey, what’s this about?’ He said, ‘Oh I don’t butcher the animals, that’s up to you.’

“Now it’s about two hours before we open and I’ve got a cow. I call the head of the municipality and ask if I can park the cow for the evening in the grass, on municipality land. He tells me to go to hell and to take the cow with me, whatever. It’s getting closer to opening and I’ve got this cow to worry about. I finally find a butcher and he walks in and people are starting to come in to the restaurant and they see what’s going to happen. The women are starting to sob hysterically, they’re screaming. The men are laughing like madmen. It’s a small outdoor restaurant, blood is actually splashing on people.

“The place is a mess. The cleaning crew is made up of Indian migrant workers, Hindus. They walk out, they’re furious. ‘Mr. Olivier, you’ve done something really bad.’ The men dining are asking for organ meats, which I cook and serve at their table. The diners are getting more and more drunk, but there was also something about actually slaughtering a cow in public. It reminds you of where the word carnival comes from. Maybe it was also a full moon.”