These days M. Paul Friedberg is looking like one lucky guy. A retired modernist landscape architect in his late 80s, he has only a few purportedly important projects to his credit, and his reputation rests largely on an innovative approach to playground design. A few years ago, Congress redesignated his derelict Pershing Park (1981), situated just east of the White House and Treasury Department along Pennsylvania Avenue, as a World War I memorial, authorizing the park’s much-needed “enhancement” with “appropriate sculptural and other commemorative elements, including landscaping.”

But it turns out the federal Commission of Fine Arts, which reviews such projects in the nation’s capital, is determined to retain the essence of Friedberg’s Pershing Park—especially qualities associated with its now-empty central pool and boxy, granite-clad fountain, which has been out of action for over a decade—even if doing so stands in the way of the creation of an appropriate war memorial.

So much for congressional intent.

Elevated above the din of street traffic by grass berms, heavily screened by trees and equipped, at its southeast corner, with commemorative mahogany granite slabs and a larger-than-life-size statue of General John J. Pershing, Friedberg’s largely sunken park features unattractive lighting fixtures and a rather drab brownish hardscape. A domed steel-and-clear-plastic kiosk, where refreshments were once sold, stands near the shallow pool, abandoned. The park is situated on a trapezoidal, 1.75-acre site along Pennsylvania Avenue between 14th and 15th Streets. To the north lies the venerable Willard Hotel; to the west a handsome park focused on an equestrian statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman; to the south the White House Visitor Center, housed within the vast classical pile that is the Commerce Department building; and to the east, postmodern mandarin Robert Venturi’s forlorn Freedom Plaza (1980), which, aside from a few months as a camping site for Occupy D.C. protesters in 2011-12, mainly serves as a skateboarder’s resort.

You may never have laid eyes on Pershing Park, especially in light of its lamentable condition. But this is a precious chunk of real estate, occupying a strategic node on the nation’s most important avenue. It is a fitting site for the long-overdue, appropriately monumental commemoration of a war that changed the course of Western civilization—a war in which 4.7 million Americans served and over 116,000 were killed. So far, however, the World War I memorial episode mainly provides fresh evidence of the disorientation and ineptitude of the authorities overseeing developments in Washington’s civic realm. And the wrangling over the memorial offers a case study in the barriers the nation’s cultural elites have placed in the way of clear thinking about the purposes as well as the aesthetics of public art and architecture.

Like Freedom Plaza, Pershing Park is a creation of the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation. So is a third problematic landscape to the east, John Marshall Park (1982), a verdant yet remarkably desolate expanse whose terraces descend to Pennsylvania Avenue from C Street. From 1972 to 1996, the PADC—a brainchild of Daniel Patrick Moynihan—reshaped the previously down-at-heel north side of the avenue facing the magnificent Federal Triangle complex and National Gallery of Art. Architecturally, the results ranged from the dismal modernism of the J.W. Marriott Hotel at National Place (1984) to the lively classicism of the hemicyclical Market Square complex (1989). Market Square’s plaza, with its Navy Memorial, is easily the most successful public space the PADC created.

The PADC campaign, in short, was a very mixed bag. But whereas Freedom Plaza confounds the layout of the avenue, which might be better off without it, Pershing Park occupies a block created by Peter Charles L’Enfant’s masterful plan of 1791 for the new capital. (That plan is itself inlaid at large scale on Freedom Plaza, which is bereft of the surrealistically large architectural models of the Capitol and White House as well as the pair of flattened pylons framing a vista of the Treasury Department building’s south portico that Venturi intended. The vast plaza’s only vertical elements are a couple of flagpoles.) The Pershing Park block was once occupied by residential and, later, commercial buildings, demolished after its acquisition by the federal government in 1928 to amplify views of the Commerce Department building, which was completed four years later. Since then the block has mostly served as a park, though temporary federal office buildings were erected there during World War II.

The World War I Centennial Commission, which is charged with building the World War I memorial, held a competition that yielded five more or less unpromising finalist designs in the summer of 2015. In preparing for the last round, architect Joseph Weishaar, a young Arkansas native, teamed up with veteran New York City sculptor Sabin Howard. In Weishaar’s winning entry, announced in January 2016, Friedberg’s square pool would be replaced by a grass mound enclosed on three sides by retaining walls bearing over 200 feet of narrative bas-relief and crowned by three figures in the round—an artillery crew preparing to fire a cannon.

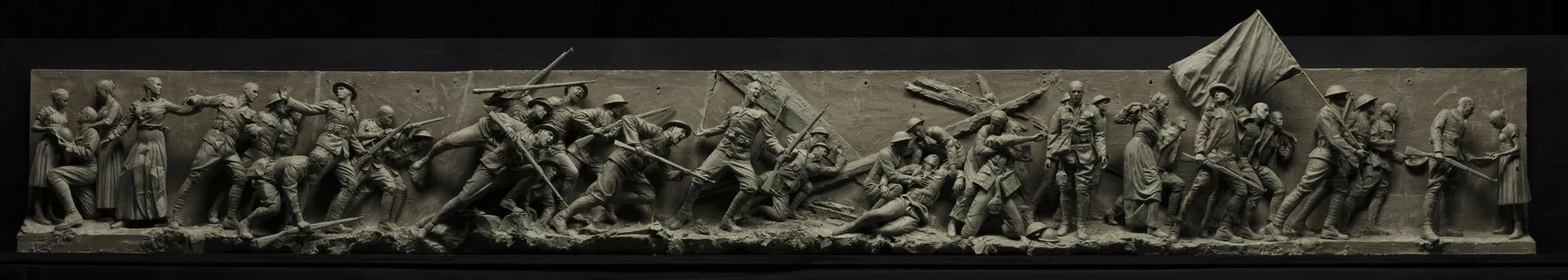

This unconventional concept has fortunately undergone serious downsizing. (The design team now includes Philadelphia landscape architect David Rubin.) The grass mound is gone. What emerged instead is a stone wall, somewhat resembling an outdoor altar, that serves as a monumental armature for Howard’s 38-figure bronze frieze—now modeled in deep rather than low relief—portraying a soldier’s journey from home front through the torments of war and back again. The frieze runs across the wall’s front. This sculpture wall would replace Friedberg’s fountain box on the pool’s western flank. (The box once doubled as a Zamboni garage because the pool became an ice rink in winter.) This sculpture wall is much broader than Friedberg’s box but is likewise set in steps descending to the pool. It is, in other words, embedded in Friedberg’s landscape. Water streams down the sides of the sculpture wall and is channeled into the pool, while new walkways running perpendicular to one another span the pool in front of the wall.

Howard’s sculptural design offers not only an allegorical narrative that is very carefully thought out as a dynamic formal composition but also an exceptionally competent rendition of the realist sculptural vernacular that, since the 1980s, has given the nation’s capital Frederick Hart’s Three Servicemen at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Frank Gaylord’s triangular formation of 19 soldiers at the Korean War Veterans Memorial, and Raymond Kaskey’s reliefs depicting wartime scenes on the balustrades at the World War II Memorial. Howard’s figure work is superior to what we see in those memorials, and it is certainly preferable to Robert Winthrop White’s muddled Pershing statue (1983), the focus of the existing memorial, which was designed by the prominent modernist architect Wallace K. Harrison in consultation with Friedberg.

The seven-member Commission of Fine Arts, chaired by National Gallery of Art director Earl A. Powell III, approved the Weishaar-Howard sculpture-wall concept in May 2017, requesting only “further study” of its breadth (which has since been considerably reduced) and more information about the treatment of the architectural structure itself and the steps flanking it. At the same time, however, Fine Arts emphasized “the fundamental importance of the design’s experiential character—including the visual, auditory, and tactile qualities of water—in making this park work successfully as a memorial.” This qualified approval has turned out, perhaps unwittingly but no less outrageously, to be a classic bait-and-switch routine based on an arbitrary assessment of “experiential character.” Fine Arts appears content to sink the Weishaar-Howard design because it considers retaining the “visual, auditory and tactile [!] qualities” of Friedberg’s pool more important than civic commemoration. This is perverse.

The Fine Arts commission’s wholly unjustified obstructionism poses a mortal threat to the entire memorial project, which relies on private fundraising and was originally scheduled for completion in time for the centennial of World War I’s end, which falls in November.

The Centennial Commission has already gone too far in its efforts to accommodate Fine Arts. It has narrowed the breadth of the sculpture wall to what Howard says is the absolute minimum—56½ feet—whereby its figures can be endowed with an acceptably monumental scale of about 6½ feet apiece. Far more problematically, the Centennial Commission has abandoned its original “integrated” wall concept in favor of a “freestanding” option that reduces the wall to something like a stone-and-bronze billboard set not in but in front of the steps. This would allow an abundance of water to flow into the pool from the flattened wall’s rear, thanks to the elimination of the U-shaped enclosure in back of the “integrated” wall that would have provided an overlook facing east. The “freestanding” design would diminish the monumental effect of the frieze’s architectural setting merely to accommodate the Fine Arts commission’s obsession with preserving the existing pool landscape as much as possible and its belated concern with the “perceived heaviness” of the integrated wall concept it approved last year. (Never mind that the District of Columbia’s State Historic Preservation Office has determined that the integrated version of the wall would fit into Friedberg’s landscape better than the freestanding version.)

But not even the freestanding approach was enough for Fine Arts. After its last meeting in May, it unctuously urged “an earnest reconsideration of the wall, sculpture and fountain beyond what has been presented,” suggesting that the freestanding wall be flipped to face west—away from the pool. This recommendation is a preposterous bureaucratic tergiversation. Howard’s relief has been modeled with the expectation that it would be elevated just over three feet above the walkways, so that visitors would approach it on a level plane and gradually proceed from general views to particular aspects of the composition. The flip recommended by Fine Arts would ruin this sequence: One would step down to the sculpture wall, and closer-range movement in front of Howard’s relief would be constricted. More importantly, this recommendation would leave the pool, the existing park’s central feature, and thus the memorial itself, devoid of an indispensable symbolic focus. The result would be not a World War I memorial but a disjointed park that happens to contain two memorials. (Fine Arts also has belatedly and unhelpfully suggested that the kiosk, which is situated just east of the pool, might serve as the site for a circular sculptural composition. This too would be completely incompatible with Howard’s design.)

The location and orientation the Centennial Commission has proposed for Howard’s relief seems to be the only one that makes sense. On the other hand, there is no question that the sculpture wall’s water feature and the walkways require careful study. And the cluster of flagpoles the Centennial Commission has proposed does not appear to be the best use of the kiosk site. The kiosk might well be refurbished—starting with the replacement of its discolored plastic glazing with the glass Friedberg specified in his design—to serve more propitiously this time around as a refreshment stand as well as a visitor facility.

Fine Arts, alas, isn’t the only problem. In 2016, months after the Weishaar-Howard design prevailed in the memorial competition, Pershing Park was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in a report commissioned by the National Park Service. This means the Centennial Commission could face litigation over the memorial, and a leading candidate for bringing suit would be the Washington-based Cultural Landscape Foundation, a 20-year-old organization founded and directed by Charles A. Birnbaum, a vocal opponent of the Centennial Commission’s sculpture-wall concept. Birnbaum formulated guidelines for landscape preservation years ago as coordinator of the NPS’s Cultural Landscape Initiative. In 2012, his foundation joined the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota in a successful suit to prevent demolition of Friedberg’s Peavey Plaza in Minneapolis (1975), whose $10 million restoration is now underway. Birnbaum, also a journalist and visiting professor at Columbia University, is an exceptionally able cultural operator who, it should be noted, has gone to bat for traditional as well as modernist landscapes.

The NPS Pershing Park eligibility report simply regurgitates the defective logic that guided the Friedberg design. In an attempt to respond to the automobile traffic on three sides of his park—the fourth side, a stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue on the park’s northern flank, is not heavily trafficked—Friedberg ran his grass berms, bedecked with rows of honey locusts, along its east, south, and west perimeters. The southern berm, the highest and longest of the three, is particularly unfortunate, creating an urban dead space for an entire city block—directly across the street from the White House Visitor Center, which receives tens of thousands of visitors monthly. Only on the north side, where Friedberg housed willow oaks in a diagonally zig-zagging array of square granite planters running parallel to the avenue, can his design be described as reasonably open for a downtown park. The planters are abutted by steps leading down to the poolside terrace with the kiosk, this terrace being agreeably paved in Belgian blocks arrayed in a fish-scale pattern. But from its western flank along 15th Street, facing the Sherman park, Friedberg’s landscape presents an amorphous spectacle that is not terribly inviting. Long semicircular steel-mesh benches literally turn their backs to that street. He made no effort whatsoever to create an axial relationship between the two parks, as L’Enfant would not have failed to do.

Pershing Park’s emphasis of spatial enclosure rather than openness to its urban setting is hardly conducive to a sense of security, and for many years the park’s denizens have tended to be marginal characters. One might question the Fine Arts commission’s assertion that the park’s problems are “the direct result of inadequate maintenance.” This is curiously reminiscent of the rationalization of the failure of Brutalist housing projects in this country and Europe as a simple matter of “inadequate maintenance.” No doubt the inadequacy has been real in both cases, just as there can be no doubt the problems have run a whole lot deeper in both cases.

Needless to say, the historic register eligibility report provides no perspective on these issues. It misses the elephant in the room—the anti-urban impact of the berms, especially the southern one—along with notable details like the obviously cramped and inadequate space allowed for reading the Pershing quotation extending across the back of the slab that serves as a backdrop to White’s statue.

Pershing Park does appear to have exuded a measure of picturesque charm in its early days thanks largely to the alteration and supplementation of Friedberg’s planting scheme by the landscape designers Oehme, van Sweden and Associates, whose lush and colorful array of plantings extended right down and even into the pool, where lily pads once flourished. (Friedberg’s crape myrtles continue to add welcome splashes of color amidst the prevailing gloom.) Such a landscape, sans berms, might have served nicely as a garden for a museum, conservatory or other well-endowed institution, where scrupulous maintenance could be expected. This isn’t a realistic prospect for a city park in Washington, including one under NPS jurisdiction as Pershing Park is. The NPS isn’t exactly famous for quality maintenance of its D.C. parks that lie outside the hallowed confines of the National Mall.

Merely restoring Friedberg’s existing landscape, which would be costly, would in all likelihood simply inaugurate another cycle of deterioration and obsolescence. The most promising way to preserve the existing park to a significant degree is to incorporate a powerful monument that can capture a much bigger share of the many millions of tourists who troop along Pennsylvania Avenue each year. Such a flow might well make the park more inviting to the public at large. A renovated kiosk refreshment stand and the Belgian-block terrace, equipped with attractive seating, could enhance the memorial’s allure, not least for local office workers on lunch or coffee breaks. The memorial’s $42 million price tag includes both renovation of the park and an endowment for its future upkeep as part of the memorial.

Fine Arts, alas, would appear to be deaf to such reasoning. Elizabeth K. Meyer, the commission’s outspoken vice chair, is a conspicuous part of the problem. A professor of landscape architecture at the University of Virginia, she contributed to a 1999 primer on modernist landscape preservation edited by Birnbaum. Her scholarly pursuits have yielded essays with titles like “Slow Landscape: A New Erotics of Sustainability.” Her online faculty profile commences thus: “Landscape architecture is a socio-ecological spatial practice with its own vocabularies and theories, yet discourse about the designed landscape is hampered by reliance on interpretations by those outside our field.” This is precisely the mentality that, beyond nurturing nonsensical productions like the historic register eligibility report for Pershing Park, produces pathologically insular, self-regarding cliques that look for ways to impose their “theories and vocabularies” on the public whether the public likes it or not. Historic preservation is one such vehicle. It has not only been hijacked but weaponized by a modernist apparat since emerging as a major cultural force in the wake of the unconscionable demolition of New York City’s majestic Pennsylvania Station half a century ago.

Meyer, one of three modernist landscape architects serving on the Fine Arts commission (which is maybe three too many), outdid herself at the May hearing, lecturing the Centennial Commission and its designers in a manner more becoming a slightly unhinged schoolmarm than a professor at Mr. Jefferson’s university. She upbraided them for their “stubbornness” for adhering to a design concept she and her colleagues approved last year—even though the Centennial Commission has literally, and regrettably, taken a big chunk out of that concept to address the Fine Arts commission’s remarkably inane concerns. She declared that “arguing” about the sculpture wall’s breadth “is not the solution,” when it is Fine Arts that has repeatedly raised the issue. She called the integrated wall “a massive intrusion into the Friedberg park,” even though monuments do tend to be massive and this project is not about “the Friedberg park,” but rather creating an appropriate war memorial in line with the park’s statutory redesignation. Meyer went so far as to criticize Howard personally for not being “as open creatively as you need to be to work in the public realm,” as if she had been a model of open-mindedness during this sorry episode. On the other hand, Meyer did manage to offer Howard some advice straight out of the depths of the swamp: Sit still and pay attention so your project can reach a happy review-board conclusion like Frank Gehry’s ludicrous theme-park scheme for a Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, with its humongous open-work stainless-steel billboard and kitschy sculpture.

It so happens Uncle Sam is footing the bill for Gehry’s $150 million boondoggle, which would never be built if that weren’t the case. The Centennial Commission is in a very different boat. Unlike the Eisenhower Memorial Commission, its membership does not include senators or representatives, and there can’t be much of a veterans’ lobby to support it when the last known veteran of World War I died in 2011. Completion of the World War I memorial has now been pushed back to 2021, and continued resistance from Fine Arts (not to speak of a historic preservation lawsuit) could cause the project’s donor support to dry up.

The Centennial Commission returns to Fine Arts on July 19.