At the death in 1953 of Bill Tilden, generally acknowledged to have been the best tennis player in the history of the game, the sports columnist Red Smith wrote: “And so it ends, the tale of the gifted, flamboyant, combative, melodramatic, gracious, swaggering, unfortunate man, whose name must always be a symbol of the most colorful period American sports have known.” That period, the 1920s and early ’30s, was a time when, in their various sports, Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Jim Thorpe, Bobby Jones, and Red Grange were also in their glory. While the fame of these other athletes was largely American, Tilden’s was international. Great as Ruth, Dempsey, Thorpe, Jones, and Grange were, only Tilden changed the nature of the game he played. Al Laney, a sportswriter famous in his day, called Bill Tilden “our greatest athlete in any sport,” tout court. In a 1950 Associated Press poll of the nation’s top sportswriters and broadcasters, he was selected as the best tennis player of the first half of the 20th century—and by a far wider margin than any of the athletes selected for other sports.

The reason that Red Smith, always a careful writer, ended his list of seven adjectives with “unfortunate” has to do with the scandal that marked Bill Tilden’s last years and marred much he had accomplished on the courts. One likes to think that achievement outlives scandal, that the former is permanent, the latter ephemeral, but in Tilden’s case it is far from certain that this has been so. In an otherwise storied life, the Fates wrote Bill Tilden a dark last chapter.

In November 1946, Tilden’s 1942 Packard Clipper was pulled over by a Los Angeles policeman for zigzagging on Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills. The policeman discovered Tilden in the passenger seat, his arm around a 14-year-old boy at the wheel the four fly buttons on whose trousers were undone. Homosexuality in that less tolerant day than ours would have been troubling enough for Tilden’s reputation, but sex of any kind with a minor was, then as now, unforgivable. Richard Maddox, Tilden’s lawyer, said at the time that the toughest cases to defend were those that entailed crimes against dogs and children.

Tilden pled guilty not to “lewd and lascivious behavior with a minor” (a felony) but to “contributing to the delinquency of a minor” (a misdemeanor). He was sentenced to five years’ probation, the first nine months of which were to be spent in jail. Not quite three years later, Tilden found himself in front of the same judge for similar charges: sex with a minor boy. This time he was sentenced to a full year in jail. All but a few of his old friends deserted him, his earnings through giving tennis lessons to celebrities were greatly curtailed, and in many of his old haunts—country clubs, Hollywood society, his birthplace of Germantown, Pennsylvania—he became non grata. The mighty have rarely fallen further.

As for Bill Tilden’s mightiness, one need only consult the record book for certification: He is the only man to have won the American singles title six years in a row and seven times in toto and the U.S. Clay Court title another seven times. He was America’s top-ranked player every year between 1924 and 1934. He played in more Davis Cup matches—28—than any other amateur player and was the first American to win at Wimbledon, which he did on three separate occasions, the last time when he was 38. His various doubles and mixed-doubles championships are nearly beyond counting as are his victories in lesser tournaments. Along the way he invented the drop shot; was the first player precisely to formulate court strategy in a book (said to be the best on its subject ever written, called Match Play and the Spin of the Ball); and early advocated open tennis, in which professionals and amateurs could meet in the same tournaments and which is in place today. He found tennis an upper-class, rather prissy country-club weekend activity and left it a sport that captured worldwide attention.

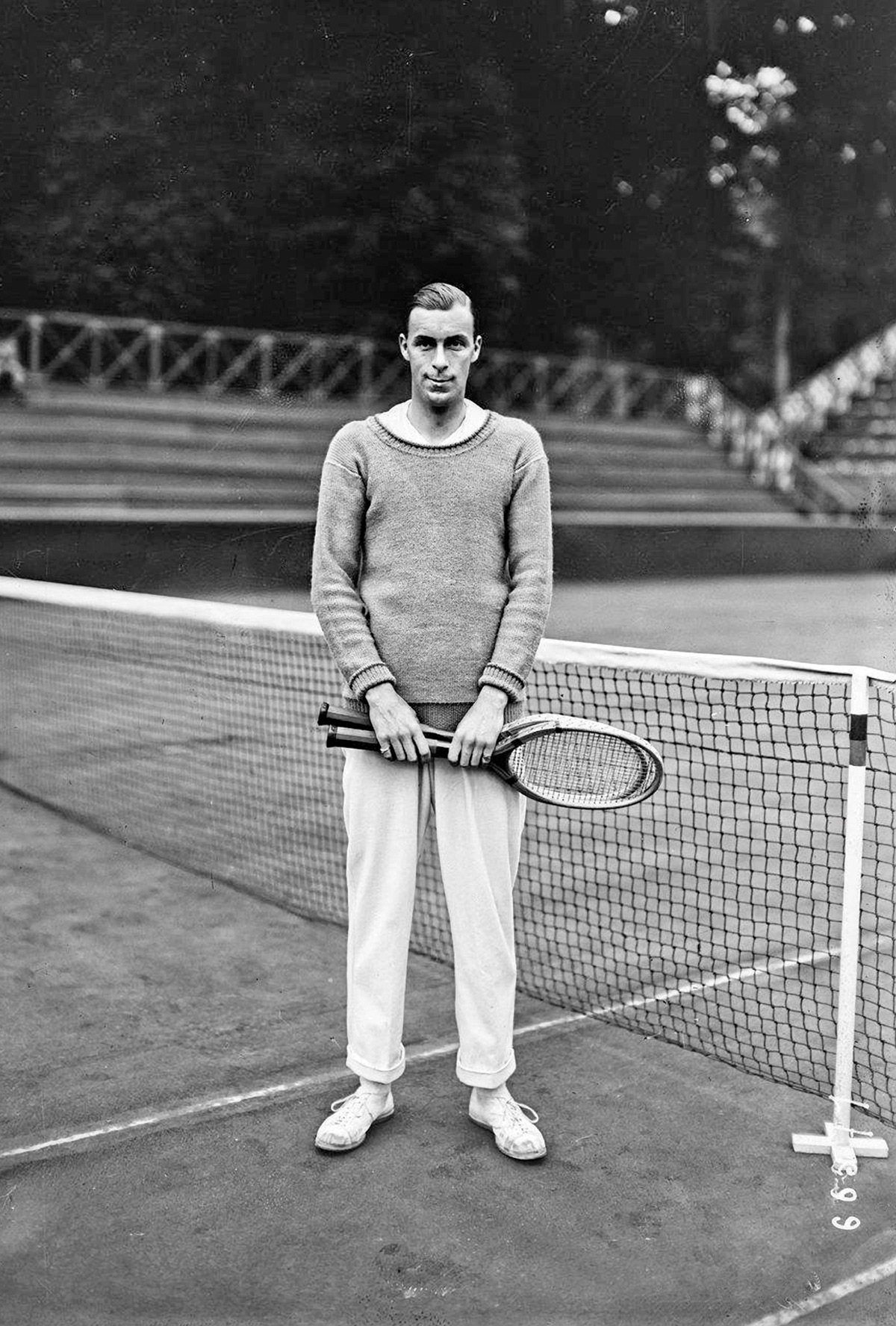

“Big Bill” was Tilden’s sobriquet, though at 6-foot-2 and 155 pounds he wasn’t as big as all that. (Roger Federer and Rafa Nadal are both 6-foot-1, and 5 of the currently ranked top-10 male players are 6-foot-5 or above.) The reason for the sobriquet is that Tilden’s most insistent rival during his competitive years was a Californian named William Johnston, who was 5-foot-8 and 130 pounds—not as small as all that either—which nonetheless allowed journalists to confer upon him the moniker “Little Bill.” Nor did Tilden play, or indeed care for, “big game” tennis, which is built on a powerful serve followed by a rush to the net for a quick kill on the volley. Tilden commanded a thunderous cannonball serve, which he used infrequently, but he much preferred to win from behind the baseline with devastatingly accurate ground strokes, which arrived with a bewildering assortment of chops, slices, spins, and blistering drives that could twist the racquet out of his opponents’ hands.

Astonishing in his ability to retrieve shots that appeared to be clear winners, possessing a double-jointed wrist that gave him more than normal racquet control, Tilden was above all a brilliant strategist, able to depress opponents by demonstrating to them that against him, their best wasn’t near good enough. Known for his sportsmanship, if a bad call went against the man he was playing, he would sometimes purposely lose the following point or give away the game in which the call was made. He could be gracious in (his rare) defeat. He was nevertheless, as all great athletes are, imbued with an intense desire to win. And win he did, over and over, relentlessly, almost boringly, once winning 57 straight games (not sets) in tournament play, a statistic up there with Joe DiMaggio’s famous 56-game hitting streak.

Because not many people are alive today who saw Bill Tilden play the game at which he was supreme—a few snippets of him in action are available on YouTube—most people who remember him at all are likely to recall his scandal as the first, and thereby the primary, thing about him. That dreary scandal, coming at the close of a brilliant career, also poses a serious problem for biographers. The problem is how great an emphasis to place on his homosexual pedophilia in recounting his life. In one of the leading biographies of Tilden, Frank Deford’s Big Bill Tilden: The Triumphs and the Tragedy (1976), sex is front and center. In the most recent biography, American Colossus: Bill Tilden and the Creation of Modern Tennis by Allen M. Hornblum, Tilden’s pedophiliac scandal is treated as ultimately peripheral, and in fact the subject is only introduced on page 383 of the book’s 405 pages of text.

Who is correct, Deford or Hornblum, and how might we judge? Before attempting that judgment, though, two questions arise: In biography, do we really need to know much of a detailed kind about the subject’s sex life? And, even if we feel we do, can we truly expect to acquire such knowledge—of longings, fantasies, and above all the peculiarities of practice—with anything resembling useful precision? Homosexuality makes both questions even more complicated, for much about the nature of homosexuality, including its origin, remains unknown. What is known is that in its practice homosexuality is quite as various as heterosexuality. Bill Tilden’s own homosexual practice, or what from friends, enemies, and at least one psychiatrist we have been told about it, is a case very much in point.

William Tatem Tilden Jr. was his parents’ fifth child. The first three died of diphtheria in 1884. A fourth child, a seven-years-older brother, Herbert, was his father’s favorite son. William Junior, or June as he was known when a boy, fell under the tender care of his mother, who, given the death of her first three children, worried greatly about his health. His mother was, in the old-fashioned term, musical and conferred on her son Bill Jr. a lifelong aesthetic yearning.

The Tildens were wealthy and socially prominent in Philadelphia. Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft were houseguests at Overleigh, the family mansion in Germantown, then a posh suburb of Philadelphia. William Tilden Sr., the dispenser of many civic good works and often mentioned as a candidate for mayor of Philadelphia, after his death had a grammar school named for him.

After suffering with Bright’s disease, Tilden’s mother died in 1911, when he was 18. Four years later his father and older brother died, a few months apart. He was left alone in the world with an inheritance of some $60,000—a substantial sum that would have been greater but for his father’s mistaken investments late in life—and no clear vocation. Tilden’s first job, after dropping out of the Wharton School of Business, was working on a newspaper. He would later write plays, in some of which he acted; after establishing fame through tennis, he also occasionally acted in plays on Broadway. He wrote fiction, much of it about tennis (and moralistic in the young-adult mode), and autobiographies and was perhaps at his best writing instruction manuals about how to play tennis.

In American Colossus Allen M. Hornblum earnestly sets out Tilden’s off-the-court accomplishments in a manner that might make one think the great tennis champion, in that overused and hence much cheapened term, a Renaissance man; in fact, he comes right out and calls Tilden “as close to a Renaissance man as the American athletic community ever produced.” Frank Deford, were he alive, might chime in, yeah, sure, the renaissance in the microstate of Andorra maybe. Deford has a considerably less charitable opinion of Tilden’s aesthetic achievements and quotes resounding critical putdowns of his dramatic performances: A critic in the old New York Herald-Tribune, for example, writing of one of his acting stints on Broadway, noted: Tilden “keeps his amateur standing.”

Deford writes confidently about Tilden’s sex life, sometimes on matters he cannot have known with any certainty. By the time of his mother’s death, Deford writes, “he understood, surely, by now, that he was a homosexual.” Elsewhere he writes, again about what he could not know, that “for as much as Tilden was a homosexual, it was because he chose to be one, not because he had to.” Nor could Deford know, as he writes, “that it is clear that Tilden was never an intensely sexual person.”

Reporting the conversation and opinions of others about Bill Tilden’s homosexuality, Deford seems on solider ground. Ty Cobb, never noted for his exquisite sensitivity, on first seeing Tilden is supposed to have said, “Who is this fruit?” Henri Cochet, one of the French tennis players, known as the Four Musketeers, who dominated tennis in the 1930s, said that Tilden “was always having difficulties with the police for soliciting little boys. But Americans are so sensitive about questions of morality. It was his business and it didn’t interfere with his tennis.” The journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns allowed Tilden to give lessons to her son only after he promised to keep his hands off the boy. In Sporting Gentlemen, his history of tennis in America, E. Digby Baltzell notes that “Tilden’s effeminate mannerisms became more and more obvious as he grew older.”

In Hornblum’s American Colossus, Bill Tilden is, until the book’s final pages, sexless. Relations with women are scanted; the prospect of marriage is never in question. After filling in the Tilden family’s history and Bill Tilden’s early years, Hornblum concentrates almost wholly on his subject’s on-court accomplishments. Hornblum provides a lengthy chapter on Tilden’s having lost, owing to an infection, half the middle finger on his right hand (his playing hand) and his heroic return to tennis after what many thought a permanently disabling accident. Hornblum also devotes several pages to Tilden’s work developing a slashing backhand, an offensive weapon that vastly improved his game. Tilden, who barely made his college team so erratic was his play, did not attain his tennis supremacy until he was 27, late for a player in that or in any other time, and it was his deadly backhand that made this supremacy possible. “I have never regretted the hours, days and weeks that I spent to acquire my backhand drive,” Tilden wrote, “for to it, and it primarily, I lay my United States and World’s Championship titles.”

As does Frank Deford, Allen Hornblum expends many pages on Bill Tilden’s career-long battles with the United States Lawn Tennis Association. More than once, the USLTA attempted to suspend Tilden because he was earning money writing newspaper articles about tennis while himself playing it. Tilden also fought with the USLTA over expense money allowed amateurs, for he was himself always a big spender—“He traveled like a goddamn Indian prince,” said Al Haney—a man who, when it came to travel and dining, knew none other than first-class. Throughout his career Tilden was a consistent opponent of the USLTA’s “shamateurism,” the arrangement whereby everyone but the players profited from the game.

A leitmotif in American Colossus is Bill Tilden’s work coaching young players. Early in his career he returned to coach his old high school tennis team. He claimed he learned much himself through teaching. Throughout his career he cultivated promising young players, attempting to imbue them with his own strategic approach to, and passion for, the game. He would have some among them while still in their adolescence—the future champion Vinnie Richards is a notable example—play as his doubles partners in major tournaments. Allen Hornblum reports all this in the most straightforward way. In doing so, he quite forgets that a dirty mind never sleeps, and readers who come to his book aware of Tilden’s scandal cannot but wonder if along the way he didn’t attempt to seduce these boys, or if his experiences with them aren’t foreshadowings of the scandal that lay ahead.

In Frank Deford’s pages we learn that Tilden did not sexually abuse any of these boys, but remained “scrupulously proper.” His sexual taste, Deford reports, ran to the adolescent equivalent of “rough trade”: bellhops, newspaper boys, and the like. Even here, though, perhaps owing to his fear of venereal infection, his activities, again according to Deford, were restricted to fondling and being fondled. Hornblum mentions none of this.

But, then, Allen Hornblum is not greatly attentive to his reader’s interest or patience. He recounts several of Bill Tilden’s important five-set matches at a length that feels only slightly shorter than the matches themselves. Nor is he highly attentive to the English language. He misuses the words “enormity” and “peruse,” “replicate” and “definitive,” and greatly overuses “iconic.” He specializes in the flaw that H.W. Fowler termed Elegant Variation—calling the same thing by several different names. So Bill Tilden is at one point the “Penn netman,” at others “the long-limbed, multi-talented Philadelphian,” “the lanky Philadelphian,” and “the tall, cocky Philadelphian.” Bill Johnson, it will not surprise you to discover, was also “the diminutive Californian with the big heart.” Switzerland is elegantly varied to become “the mountainous country.” Whenever Hornblum encounters an infinitive, he generally pauses to split it.

Hornblum is also either inordinately enamored of, or more likely fails to recognize, clichés. William Tilden Sr. was born in a town that “nestled along the banks of the Delaware River”; after his death, his son was left in “the capable hands” of his cousin Selena. Summer matches in his pages are played in heat that is “sweltering,” dies are “cast,” professors “stodgy,” and with rain in the offing skies, yes, you will have guessed it, “grow more ominous.” Bill Tilden, meanwhile, was a man in whom “there was no quit,” clearly “not one for throwing in the towel”; he was “special,” and the rest, you might say—Allen Hornblum, alas, does say—“is tennis history.”

In his last pages, Hornblum argues with Frank Deford’s interpretation of Bill Tilden in the biography Deford published 42 years ago. (Deford is not around to respond, having died last year.) He allows that Deford’s book is “entertaining,” adding “how could a book about Tilden not be,” without realizing that he himself has come perilously close to bringing off this difficult task. Hornblum argues against Deford’s claim that Tilden’s last years, the years after his scandal, were dark and desolating. He was, Hornblum claims, nowhere near as broke as Deford reported, nor so gone to seed in appearance, nor so bereft of friends.

Allen Hornblum’s real complaint is about what he calls “Deford’s melodramatic psychobabble” in his interpretation of Tilden’s homosexual pedophilia. Here Hornblum fails to distinguish between psychology and psychobabble, for the former does not invariably issue in the latter. Deford does not use the language of the Freudian or any psychological school. Nor are all Deford’s interpretations defaming or iconoclastic. He attributes Bill Tilden’s cultivating young tennis players, for example, to a fathering instinct. Tilden received very little attention from his own father, and he had no children of his own. That he wished to shower fatherly attention on younger players seems, far from psychobabblous, acting upon a generous emotion.

Lives, at least those deserving of biographies, require interpretation. Sometimes even an incorrect interpretation is better than no interpretation at all. (Freud said that biographical truth doesn’t exist, by which I gather he meant we cannot finally plumb to the depth of any human soul.) But American Colossus, industrious though its author has been in collecting material, by forgoing serious interpretation of its subject rarely rises above the level of fan admiration.

Great athletic prowess is not so much a gift as a temporary loan from the gods—one usually called in no later than the age of 40. Greatness in any other line—art, philosophy, politics—is longer-lived. That the athletic gift is shorter-lived is what gives even the greatest of athletes, no matter how extensive their fame, how grand their emoluments, a touch of sadness. No longer to be able to do in midlife what one once did supremely is a cruel punishment.

When Don Budge, the next great American tennis player after Tilden, asked him what he would do when he was no longer able to play tennis, Tilden looked at him and replied: “Hmmmph. Kill myself.” Bill Tilden did not of course kill himself. But without tennis to sustain him, he gave way to his worst and apparently long-repressed impulses and thereby came close to killing his own reputation as the greatest player in the history of tennis.