The Trump administration plans to repeal, reject and otherwise root out climate change policies that the president sees as undermining his pro-growth, America First agenda.

But a detailed look at climate offices embedded in agencies across the federal government show that it will take more than a stroke of the presidential pen to make that happen.

A big problem for President Trump is that much of the federal policy apparatus that directs climate change activity is deeply and structurally embedded in the federal bureaucracy, and has been relatively untouched by the new administration. This is especially the case because former President Barack Obama’s fiscal 2017 budget continues into the fall.

“I do think Trump can get a handle on it,” but “he got his clock cleaned in the first budget negotiation,” said Caleb Rossiter, author and foreign policy expert who serves as adjunct professor at American University in Washington. He was referring to Congress’ extension of the fiscal 2017 budget in a spending bill through the end of September. A number of GOP pundits were angered that none of Trump’s fiscal 2018 budget blueprint ideas were included in that measure.

The Trump administration plans to repeal, reject and otherwise root out climate change policies that the president sees as undermining his pro-growth, America First agenda.

Rossiter, whose left-liberal credentials included a stint as counsel to former Rep. Bill Delahunt, D-Mass., who was one of Nancy Pelosi’s lieutenants after she swept to power in 2006, is a fervent supporter of clean fossil fuel development, and is sympathetic to Trump’s agenda. He made a name for himself for being a Democrat who is also a fervent critic of alarmist climate policy. His willingness to reject an article of faith in leftist and Democratic circles got him ousted a few years back from the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, where he was an associate fellow.

The budget spending bill approval during Trump’s early days in office showed that Obama’s funding goals won’t be changed much this year. But they are fueled by the idea of an impending “climate catastrophe,” rather than by science, Rossiter says.

“So, there wasn’t much change at EPA this year, not much change at [the] State” Department, Rossiter says. People say Trump will “get it right next time” when it comes to the budget, Rossiter adds, but he isn’t convinced.

“It’s going to be hard … and this stuff is really deeply embedded in the budget. People are doing National Science Foundation studies, transportation studies based on the assumption that carbon dioxide is a clear and present danger to our country.”

Another long-term problem is that Obama planted climate change offices in Cabinet agencies all over the federal government. These climate offices are meant to direct, advise on, and recommend actions that have climate change as their guiding star. Their whole point is to ensure that federal agencies only approve projects that consider the climate consequences of government action.

Although the creation of some of this climate change infrastructure can be traced back to Republican President George W. Bush, the last eight years under Obama deepened and codified the climate change network and ran it through the warp and weft of the Washington bureaucracy.

It has almost gotten to the point where all governmental action has an element of global warming activism in it, Rossiter says.

Deep network

Some of these climate offices and agencies include:

- The State Department’s Office of the Special Envoy for Climate Change, or the SECC, which is responsible for negotiating climate deals and implementing U.S. policy on climate change.

“As part of this work, SECC led the way in the negotiations in Paris at the 21st Conference of Parties to the [United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change],” according to the State Department website. “The Paris Agreement is the most ambitious climate accord ever negotiated, and its rapid entry into force demonstrates the commitment and urgency of the international community to work together as it grapples with the growing threat of climate change.” The statement is still on the department’s website, despite Trump’s June 1 decision to withdraw America from the Paris deal.

The State Department also has an Office of Global Change, which represents the nation in any negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which is the same convention that handled the Paris negotiations with 194 other countries. It also handles negotiations with other international organizations that handle climate change policymaking, including the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization. The office also leads U.S. government participation in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which assesses scientific and technical information related to climate change,” according to the State Department. The intergovernmental panel is the scientific board that determines the science that most countries use to interpret the rate of climate change due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and other manmade activities.

“The office is further responsible for coordinating a number of bilateral and regional partnerships on climate change, as well as foreign assistance related to clean energy, adaptation, and sustainable landscapes,” according to the State Department.

- The U.S. Agency for International Development also has its own specialized Office of Climate Change. USAID is the nation’s primary distributor of foreign aid, and climate change is seen by the agency as one of the primary reasons its services are in greater need than ever before.

The office helps shape the agency’s aid to other countries based on a core aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It weighs projects for being climate-friendly, not just for their ostensible purpose, such as supplying energy. It funds programs such as green jobs initiatives in Rwanda, where aid money is used to install solar panels.

USAID spends more than $300 million per year in 50 countries for “climate-smart development,” according to the agency. “About two-thirds of this support is delivered in-country by USAID missions. One-third is delivered through regional and global programs, which provide policy and technical expertise as well as information, tools and solutions.” USAID also works with NASA to assist countries with the use of the space agency’s satellite network to plan for and combat global warming impacts such as drought.

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture has its Climate Change Program Office, which also guides the agency’s response by focusing on how global warming will affect agriculture, forests, grazing lands, and rural communities.

The program office also coordinates with other federal agencies and on Capitol Hill, and represents the agency in international climate change meetings and deliberations.

It works to ensure that climate change is recognized and “fully integrated” into research, planning, and “decision-making processes,” according to the USDA website.

- The Energy Department has at least two climate change or climate-related offices within its Office of International Affairs, overseen by the deputy assistant secretary for International Climate and Technology.

First, there is the Office of International Climate and Clean Energy, which coordinates clean energy development programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Second, there is the Office of International Science and Technology Collaboration, which oversees a number of programs with other countries to develop clean energy programs.

Energy Secretary Rick Perry announced plans this month to close these offices, but said this didn’t mean the administration is withdrawing from support of clean energy development.

He wants to increase efficiency and end duplication of one office and the next, says the agency. It has an Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, which has its own international affairs division, which will be used to conduct the duties of the two closed offices.

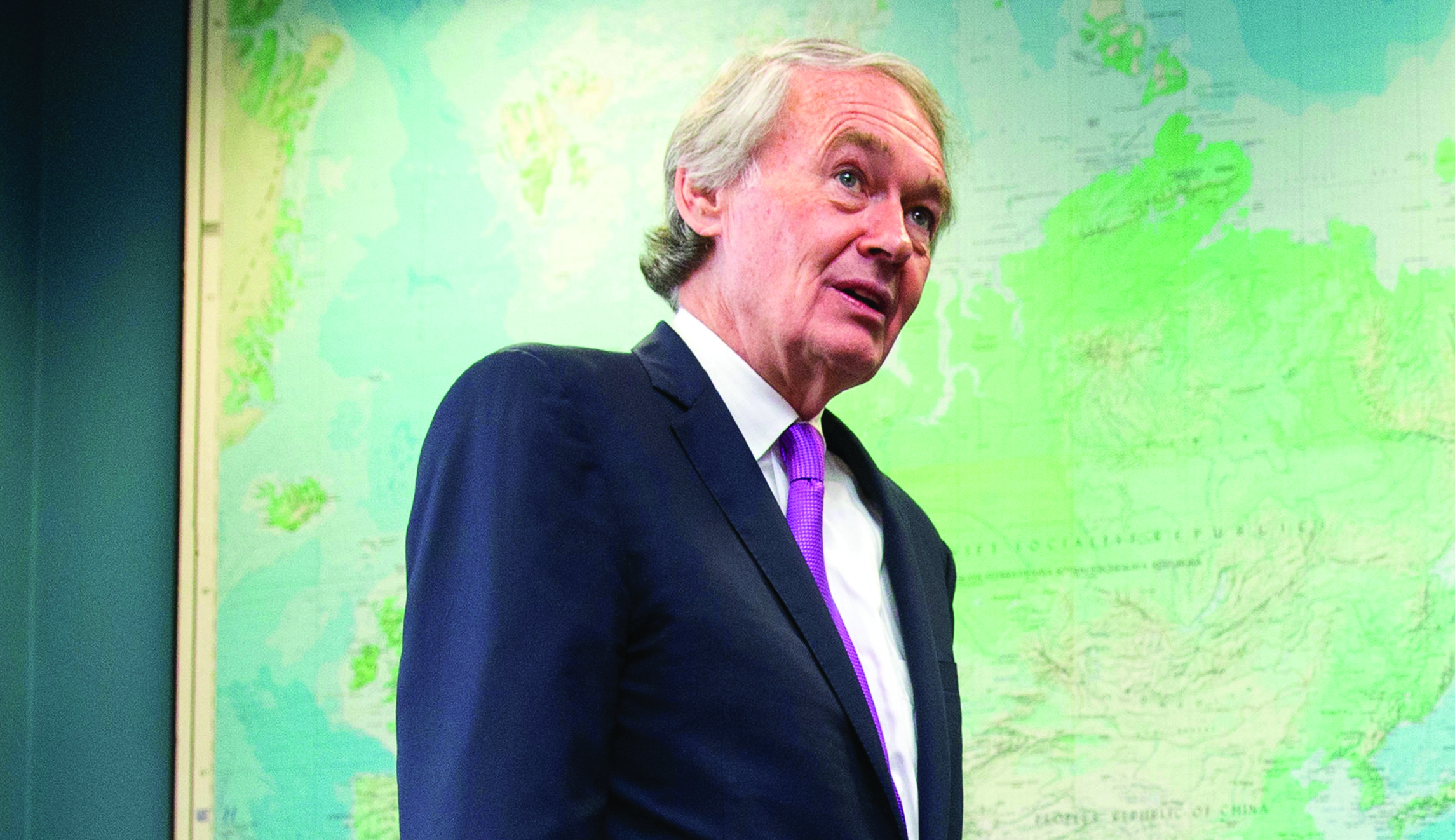

Nevertheless, the closure is receiving pushback from Capitol Hill Democrats, such as Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts, a leading advocate of policies that treat climate change as an extreme danger.

Nevertheless, the closure is receiving pushback from Capitol Hill Democrats, such as Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts, a leading advocate of policies that treat climate change as an extreme danger.

“With President Trump withdrawing the United States from the Paris climate agreement, we need offices like the OICT to help create opportunities for American business abroad in the global clean energy economy,” Markey said in a letter to Perry this month. “When we export American technology and expertise around the world to address climate change, we can create good jobs here at home. Let’s turn the lights back on at the Office of International Climate Technology so that we can help power the world with clean energy and energy efficient technologies.”

“Addressing the effects of climate change is a top priority of the Energy Department,” the agency’s website reads. “And severe weather — the leading cause of power outages and fuel supply disruption in the United States — is projected to worsen, with eight of the 10 most destructive hurricanes of all time having happened in the last 10 years.”

- The Department of Transportation is another big Cabinet level agency with climate change policy strewn through it. One of its main initiatives is the Transportation and Climate Change Clearinghouse, which is designed as a “one-stop source of information on transportation and climate change issues,” according to the agency. “It includes information on greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories, analytic methods and tools, GHG reduction strategies, potential impacts of climate change on transportation infrastructure, and approaches for integrating climate change considerations into transportation decision making.”

It also is involved in joint federal activities, such as the support of electric car deployment through the Energy Department’s Workplace Charging Challenge, which supports electric car charging available to employees across the country.

“A big one is at the bottom of your list at the Department of Transportation,” Rossiter said. “They put a lot of limitations on public transport, what can be approved, and they are very fixated on the greenhouse gas hypothesis.”

The Department of Justice has its own programs, as does the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Education, he said.

The list goes on, according to Rossiter. The Department of Justice has its own programs, as does the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Education, he said.

Another large organization that the U.S. government is a part of is the World Bank. It is set up to fund projects all over the world, but has been known to hold up coal-fired power plant projects because of the threat of “climate catastrophe,” Rossiter said.

“They’re having blackouts [in South Africa], because demand from their strong economy exceeded supply, and here we are not supporting this plant because of our fears of a catastrophe,” Rossiter said, referring to U.S. pushback seven years ago for the multi-billion dollar Medupi coal power plant in South Africa. The bank eventually defied environmental resistance, and a $3.75 billion loan was approved to construct the plant, but Washington abstained from voting to approve it. The plant is set to come online in 2018.

It will be the fourth largest coal plant in the world, and the largest coal plant to use an advanced dry-cooling system that reduces its need for water.

Next steps for Trump

Trump has taken some actions to disconnect the climate network, primarily by rolling back climate change regulations, land management decisions and international agreements such as the Paris climate change agreement. But all of these actions just scratch the surface, according to critics of Obama’s policies.

They say Trump hasn’t even begun to address the real grip that climate change alarmism had put in place within the government. Trump can turn off the engine, but other presidents can just as easily turn them on again if they are still there, which would leave Trump’s climate agenda in tatters.

Myron Ebell, Trumps former transition team leader at the Environmental Protection Agency, in the months before the decision to quit the Paris deal, has said the president’s advisers are swamp creatures.”

Myron Ebell, Trump’s former transition team leader at the Environmental Protection Agency, in the months before the decision to quit the Paris deal, has said the president’s advisers are “swamp creatures” — he cites Secretary of State Rex Tillerson — unlikely to help drain Washington’s climate quagmire.

Tillerson, with Trump’s son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner, wanted to remain in the Paris deal.

Ebell serves as director of the Center for Energy and Environment at the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, and has called loudly for Trump not to backtrack from his campaign promises to repeal climate rules and agreements.

Endangerment findings

Although Ebell supports Trump’s agenda, he wants action to unravel the legal processes that drive climate change, which he considers as great a problem as its most immediate products.

One would be to roll back EPA’s “endangerment finding,” which lays provides justification for the agency to regulate greenhouse gases.

“You need to contact your members of Congress, and you need to make noise and, particularly the scientists here, that the endangerment finding needs to be reopened,” Ebell told the annual gathering of the Heartland Institute in Washington in March.

The Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Massachusetts v. EPA case during George W. Bush’s presidency that EPA had the authority to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act. This pushed the agency to issue the endangerment finding. The EPA issues findings for new sources of pollution where it sees evidence of a risk to public health.

Trump is attempting to strike out climate regulations painstakingly one at a time, which will take years, with no guarantee that a new president wouldn’t reverse all Trump’s actions. Revoking the endangerment finding would be a more secure method, because it would eliminate the raison d’etre for carbon dioxide regulation. At least, that’s what climate skeptics hope.

Rossiter said one of the weaknesses in Trump’s decision to leave Paris was that he failed to mention global warming science. “I wish Mr. Trump would have really cut the Gordian Knot by saying for scientific reasons it’s way too premature to restrict our economy on the basis of fears of climate catastrophe,” he said.

Rossiter believes the science isn’t as strong as most people say it is for taking action to stop global warming. “The 98 percent consensus is carbon dioxide is a warming gas. And it has, probably, some impact on the temperature,” but that “doesn’t mean you are immediately creating floods, hurricanes and droughts and locusts.

It will be the fourth largest coal plant in the world, and the largest coal plant to use an advanced dry-cooling system that reduces its need for water.

“This creates a problem because what we are trying to do, what we need to do, is defang the concept that has spread through the federal government. Once it’s defanged, it’s much easier to go through the executive branch agencies and say ‘look, our goal here is clean as possible generation of electricity for the wealth of the United States and the world.'”

Obama’s carbon cost sticks

Then, there is the social cost of carbon, a metric that Obama used extensively to justify a number of regulations, which estimated the savings of taking action compared to doing nothing about climate change.

Trump’s Energy Independence Executive Order rolled back the interagency working group that Obama set up to design, and continuously modify, the social cost metric. But the metric still survives inside individual agencies and the offices that ensure its use in developing federal rules.

For example, the National Academy of Sciences this month held a conference on a report that the interagency working group requested to help refine it. The academy is quasi-independent, but relies on some government money in addition to donations from endowments and other charitable foundations.

The forum was titled, “Updating the Social Cost of Carbon and Valuing Climate Impacts: A Public Symposium.”

From this administration’s point of view, this may be an “uncomfortable situation, but it’s not like they won’t still have work to do to some extent,” said Sam Batkins, director of regulation for the conservative think tank American Action Forum.

Batkins pointed out that Trump’s executive order “said that they were going to essentially recalculate the Social Cost of Carbon, and I think that’s something that the climate offices and the economists and public policy professionals there are going to have to do.”

The interagency working group “has been disbanded, but they are going to need to come up with a figure that is more or less essentially the domestic cost of carbon that’s going to factor into [Environmental Protection Agency] regulations of the future.”

But Batkins questioned, “How many regulations is the EPA going to promulgate [under Trump] that are going to have significant effects on greenhouse gases?”