By late April 2000, Vice President Al Gore was thumping his liberal challenger Bill Bradley with 70 or 80 percent of the vote in most primary states. That same time four years later, the tent hosting Howard Dean’s populist revival had been folded for two months.

In late April 2016, Bernie Sanders is even in national polls with a former First Lady of the United States, senator, top vote-getter in a presidential nominating contest and secretary of state. And that’s just one person. Hillary Clinton is a formidably experienced politician with universal name recognition who has the opportunity to become the first female commander-in-chief. She hasn’t been able to shake a “septuagenarian socialist” who half the country had never heard of 15 months ago.

There’s clearly a unique quality to Sanders’s political rise. Slate‘s Jamelle Bouie argued persuasively that there isn’t anything new about a “progressive insurgency” of the sort the Vermont senator has staged, since there have been so many of them in past Democratic elections. But even he granted that the push behind Sanders is historically widespread—and it’s strangely timed, transpiring one-on-one against a deeply credentialed and organized candidate who is a maker of history in her own right. How has Sanders himself become all the rage, especially against a figure like Clinton?

It’s worth revisiting the topic of Hillary’s popularity to at least partly explain it. Take this headline from an April McClatchy poll: “Clinton vs. Trump: Even their supporters don’t like them”. Where Sanders’s support is fervent, Clinton’s is comparatively tepid. A Sanders supporter I spoke to at a protest rally Monday may have put it best: “No one here is a passionate Hillary supporter—if they even exist.”

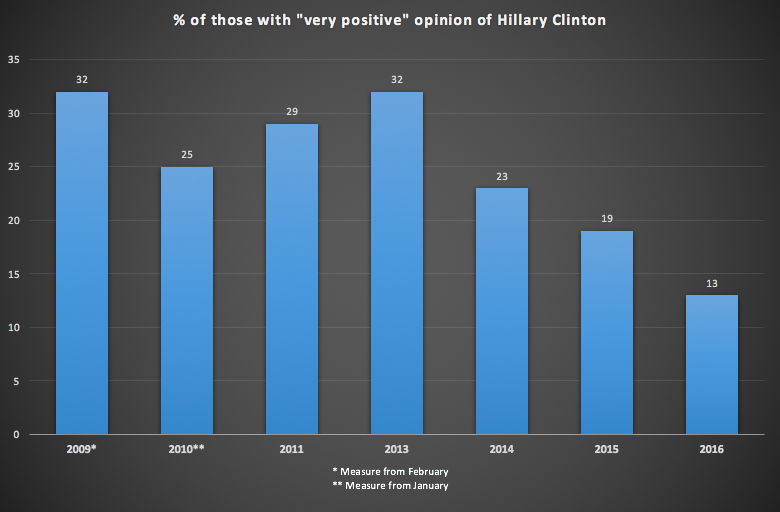

Let’s turn to the numbers. The NBC News/Wall Street Journal Survey regularly tracks the “intensity” of opinion behind particular public officials or issues. For example, dating to the beginning of her tenure as secretary of state, here is the percentage of registered voters who held a “very positive” view of Clinton (each measure taken in April unless otherwise noted):

This measure of favorability has decreased 20 points the last three years. Overall, just 32 percent have a positive opinion of Clinton (very positive plus “somewhat positive”), down from a high of 59 percent in 2009. That combined statistic was regularly above 50 percent throughout her time at the State Department.

Unsurprisingly, these declines overlap the numerous hits to Hillary’s credibility in the wake of her service to the Obama administration, including the Benghazi attacks and her email woes (the latter of which are almost certainly more likely to have an effect among the general public). Let’s peek at some numbers that reasonably could measure the fallout from them.

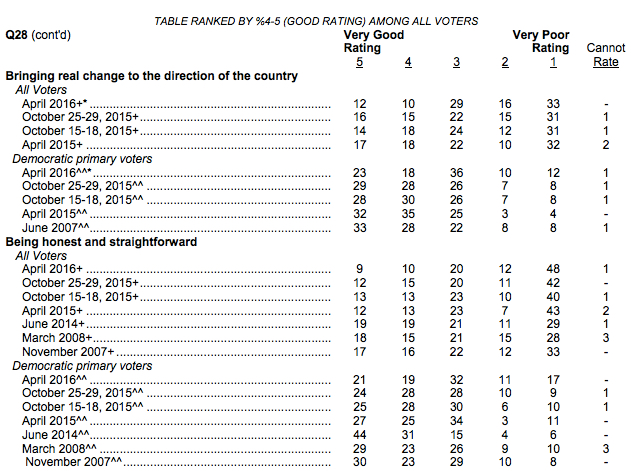

The NBC/WSJ survey has asked respondents since 2007 to rate Clinton’s honesty and straightforwardness on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “very poor” and 5 being “very good”. Over that same period, the poll has gauged Hillary’s ability to bring “real change” to the United States. The trends are awful among registered voters and Democratic primary voters alike:

Notably, the percentage of Democrats responding with a 4 or a 5 on the change question has dropped from 67 percent last April to 41 percent this month.

These data are relevant because of the general traits of anti-establishment voters. Talk to any of them and they want a change from the norm—in a candidate, someone they can trust and someone who will shake up the political system. It’s no surprise that as these attitudes have gripped the country, disparate presidential aspirants like Donald Trump and Sanders have benefitted, and traditionally establishment candidates like Jeb Bush and Clinton—their surnames representing modern political dynasties—have suffered.

Look at a different poll question, this one from CBS News, asking registered voters how much influence special interests have on Clinton and Sanders. Between November last year and April this year, the number of those saying they influence Clinton “a lot” grew from 34 percent to 45 percent, and the percentage of those responding with at least “some” has held steady above 80 percent. For Sanders, that combined number is just 39 percent.

At the same time that Sanders dominates Clinton with measures of all the personal attributes, he’s pushed her to a dead heat in nationwide polling and has mounted an unlikely resilient challenge to her coronation as the Democratic nominee. Much of it is because Sanders has tapped into the party base’s rebelliousness, more than any Democratic candidate in any recent election. In so doing, he has exploited Clinton’s support as lukewarm.