On Aug. 23, 2020, a Kenosha police officer shot Jacob Blake as he scuffled with law enforcement officers in one of several incidents that rocked the nation last summer. Riots that occurred in the ensuing days brought violence, destruction, and the national spotlight to the small Wisconsin city. The Washington Examiner recently went back to Kenosha to find out what has happened in the aftermath.

KENOSHA, WISCONSIN — Reminders of the shooting of Jacob Blake Jr. and the riots that followed are all over Kenosha.

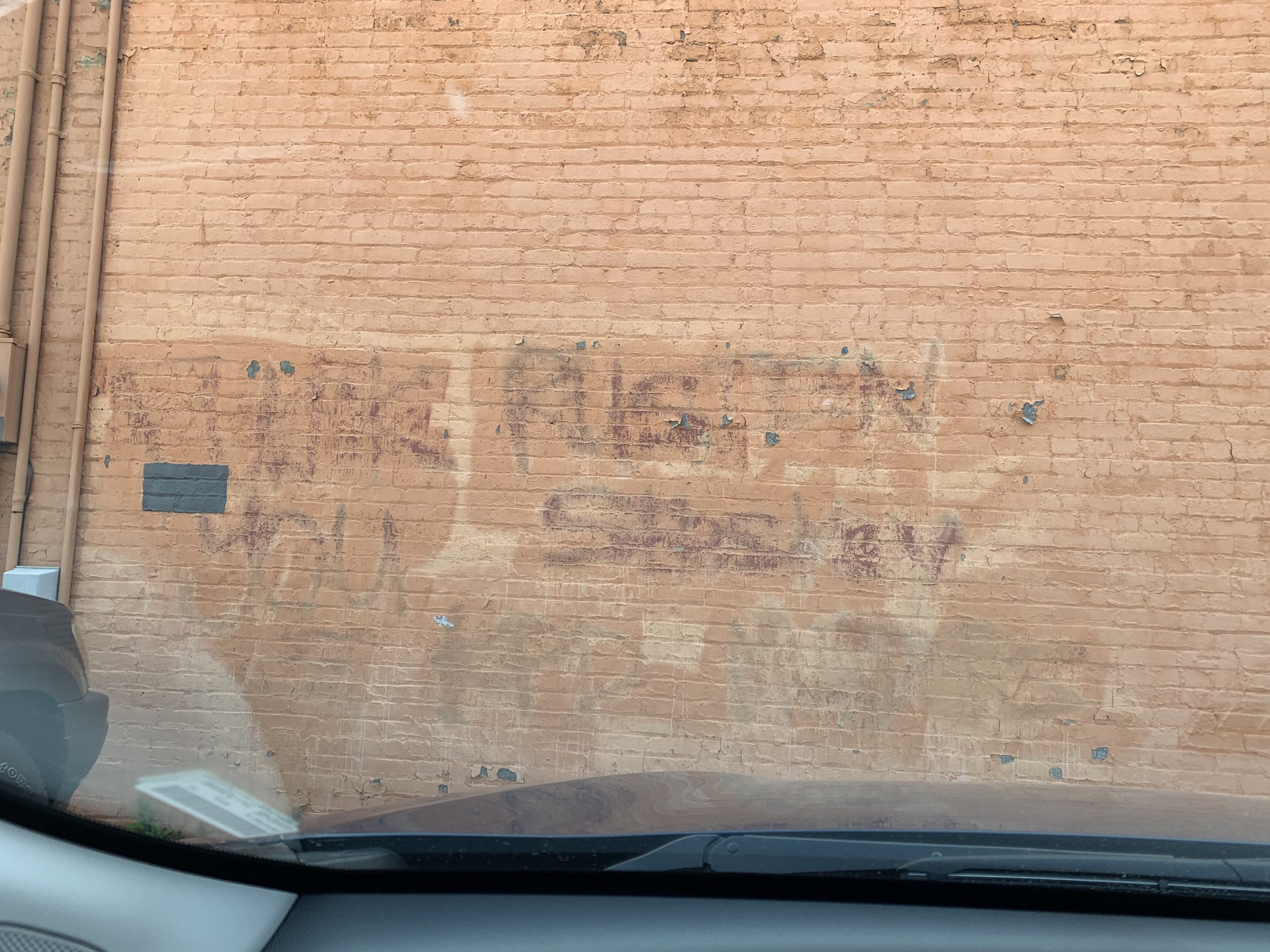

The Dinosaur Discovery Museum in the middle of town still has plywood on all of its windows. The brick wall next to Hidden Treasures on 60th Street still reads “F— you, Rusten Sheskey,” despite numerous attempts to cover it up. Graffiti on side streets and boarded-up storefronts call out “racist” police. Nine months after the small Wisconsin city of fewer than 100,000 residents was thrust into the national spotlight, it is clear that the wound is still raw.

While there have been tensions in the past between police and Kenosha’s minority residents, none has compared to the 2020 shooting of Blake.

Officer Sheskey, a white man, shot Blake, a black man, seven times in the back. No charges were filed against him.

The incident was caught on video and brought hundreds to the city nestled on the banks of Lake Michigan between Milwaukee and Chicago. The demonstrations gave way to clashes that ended with $50 million in damages, including burned buildings, looted stores, and the shuttering of a majority of black-owned businesses in uptown Kenosha.

The relationship between law enforcement and the people they were hired to police hit a low.

AFTER THE RIOTS: KENOSHA STRUGGLES MONTHS AFTER PROTEST CIRCUS LEFT TOWN

For a while, it seemed as though anybody who wanted to speak poorly of the police was given a national platform. Cable news outlets clamored for sound bites that tore into law enforcement and stoked racial resentment.

“It’s incredibly frustrating to be vilified in the national media,” Kenosha Police Lt. Joseph Nosalik told the Washington Examiner, adding that police officers have not been given a fair shake in the press. He believes that police departments are up against an “instant gratification society” that allows people to trash them without knowing the facts. Police are also not allowed to comment on active investigations, which prevents them from speaking out or standing up for themselves or their actions in real-time.

“There’s a whole lot more to the story, and the disadvantage for the police department is that in order to keep these investigations intact, to make sure that it is a fair and impartial and an unbiased investigation, we can’t get there and tell our side of the story like we want to,” Nosalik said.

After the Blake shooting, the home addresses of police officers were plastered over social media. Their families were stalked, and people showed up ready for street justice.

A white doll was found hanging from electrical wires outside the courthouse with Sheskey’s name on it.

When they weren’t being trashed in the media, the police department was taking hits from politicians on local, state, and national levels.

AFTER THE RIOTS: PASTOR AND JACOB BLAKE’S UNCLE CLAIM RACIAL RECKONING SKIPPED KENOSHA

Former President Donald Trump showed up in Kenosha to push his law and order campaign. Then-Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, during his first trip to the battleground state, told residents that the turmoil following Blake’s shooting could help Americans confront centuries of systemic racism and that the country was “getting to the point where we’re going to be addressing the original sin of this country, 400 years old … slavery and all the vestiges of it.”

“It’s almost as if police are being used as pawns in this big chess game,” Nosalik said.

As the politics played out, the Kenosha Police Department continued to be described almost daily as monsters and racists.

They went to work knowing they were hated.

Blake’s father, Jacob Blake Sr., told the Washington Examiner the descriptions fit the bill and that the police deserved the onslaught of negative press and public outrage.

“These are people hired to protect and serve, not protect and kill,” he said. “Protect one group and kill the other group. There is no patience with a white officer and a black person who they say has committed a crime.”

Part of the problem is that Kenosha has a long history of being lax on racism.

In 2020, the Southern Poverty Law Center tracked 13 hate groups with a presence in Wisconsin.

“You have this white supremacist contingent here in Kenosha, and for some reason, they feel very, very comfortable,” Dayvin Hallmon, a former Kenosha County board supervisor, toldTIME following Blake’s shooting.

Hallmon believes the underlying currents of racism have poisoned the relationship between the city’s black population and its police force and said he recalled several incidents where he felt like the police weren’t looking out for black people.

Compounding the issue is that the Kenosha police department doesn’t really reflect the people they police. There are only five black officers on the force, one Asian, and one LGBT person.

“There are certainly challenges with policing, and we would certainly love to have more people of color, more people of different sexual orientations to be out there, to be ambassadors, to show that the Kenosha Police Department embraces all of humanity and not just a certain demographic,” Nosalik said. “We’re a small police department of only 211 people, so it’s not like we have a lot of faces out there where they’re really recognized. It’s not like, ‘Oh, they really do have people who are not white.’ Predominantly, we are a white police department.”

Nosalik believes the police are facing an unfair uphill climb. Activists have demanded Sheskey be fired from the force, something he said won’t happen.

“There is no legal basis to terminate officer Sheskey,” he said. “No criminal charges have been filed against him. He has not been found in violation of any policy or procedure. To terminate him would be a wrongful termination.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Nosalik also said the police department is working on being more transparent.

“Police departments realize that we do live in an instant gratification society and that we are getting better at sharing information in a more timely manner,” he said. “Although it won’t be instant gratification, it will be a promise made that you will have information on such and such a date, and that promise will be upheld, and we will inform the public. But the process will never be as fast as ordering something from Grubhub.”