Growing dissatisfaction among families whose terminally ill loved ones face excruciating suffering has ignited debate over whether people should be allowed to control their deaths by asking doctors for lethal prescriptions.

On the side opposing assisted suicide is the Patients Rights Action Fund, led by executive director Matt Valliere. The group believes legalizing medically assisted suicide isn’t the answer to problems with how the medical system handles care at the end of life, where providers tend to pursue every intervention possible without regard to the quality of life or a person’s wishes.

Valliere said it turns out multiple other groups “from left to right, from secular to religious, and everywhere in between” don’t accept assisted suicide as a solution either. Some of them even fight each other on other issues, and that’s where the Patient Rights Action Fund comes in: to help conservatives, disability rights advocates, medical workers, and faith-based groups work together against assisted suicide laws.

Valliere, 37, has been in the role for five years. Before, he was a businessman who worked primarily in construction. Valliere joined the organization when his friend Greg Pfundstein, who is chairman of the board, asked him for help. He was reluctant initially because he wasn’t sure the political battle was winnable.

“At the outset, my original opinion was: How is it possible to bring all these odd bedfellows together? And it took a lot of work, that’s all,” he said.

The Patient Rights Action Fund is up against what appears to be widespread acceptance of medically assisted suicide in the United States. Gallup polling shows 72% of voters agree that doctors should be able to “end the patient’s life by some painless means” if they have an incurable disease, and 65% say doctors should be allowed to “assist the patient to commit suicide if the patient requests it.”

As with many people who advocate on either side of this issue, Valliere’s motivation stems from personal experiences. His father-in-law died of brain cancer, as did his friend J.J. Hanson, a husband and father who worked with the Patients Rights Action Fund during his remaining years. Hanson, who lived 2.5 years longer than doctors predicted and died at 36, warned of the dangers of making lethal drugs more widely available, sharing how his diagnosis caused him to have dark days where he considered ending his life.

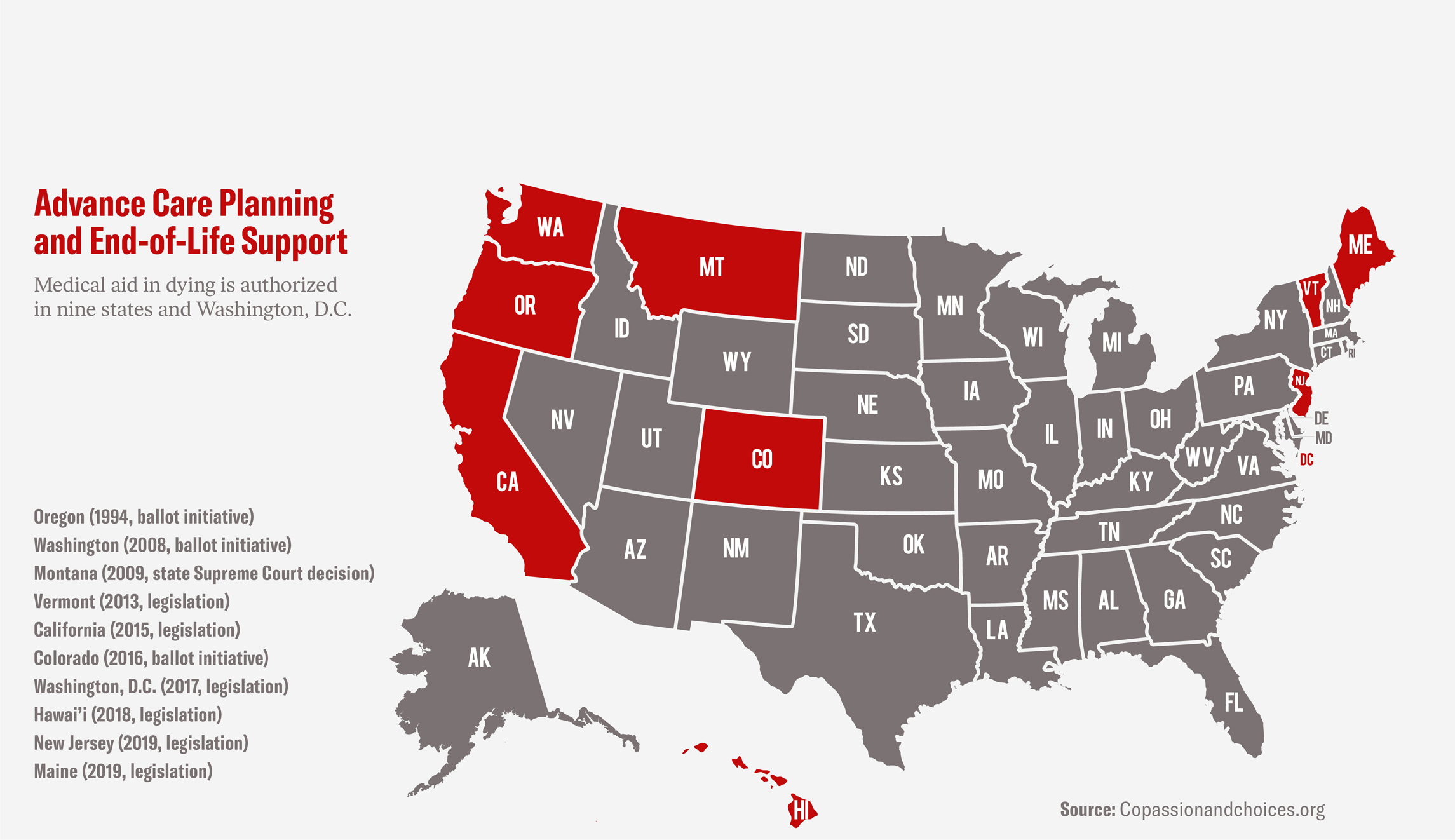

Hanson had the same kind of cancer as Brittany Maynard, the woman who became the face of what advocates on the other side refer to as the “right to die” or “aid in dying” movement. Maynard moved to Oregon to end her life in 2014 at age 29 under the state’s Death with Dignity Act, and her story has since catalyzed five more states and the District of Columbia to legalize assisted suicide.

The practice is different from euthanasia, which remains illegal in the U.S. and refers to when doctors inject patients with fatal drugs. Spurred by advocacy from the organization Compassion and Choices and by Maynard’s widower, Dan Diaz, the laws based on Oregon’s policy require two healthcare providers to confirm that a patient would otherwise die within six months. The laws also require patients to ingest the lethal medication themselves. Often, a doctor isn’t present.

Even though more states are passing similar laws, Valliere claims that his group is also seeing victories. Recent attempts at legalizing assisted suicide were unsuccessful in New York, Nevada, and New Mexico. Large doctor groups, including the American Medical Association and the World Medical Association, remain opposed to the practice.

Many who oppose assisted suicide laws worry that they will snowball into targeting vulnerable people, including those with disabilities. But to Valliere, the current laws already do that. He notes the same diagnoses that allow people to seek assisted suicide are also conditions that would qualify people as being disabled. Some of these include cancer or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

“If inherent in assisted suicide, both the public policy itself and in the practice, you have a circumstance where people with disabilities are being given a different, and not as good treatment, as those without, you have an inherently discriminatory practice in public policy,” Valliere said. “If you want to say that it’s not discriminatory, then you would have to offer it to everybody.”

Valliere, who lives in Massachusetts, grew up in a blue-collar family with a father and sister who worked with people who had intellectual and developmental disabilities. He worries about the pressure people would feel if more states legalized assisted suicide.

“I have, over the course of my life, seen different people being taken advantage of by those who should be protecting them, mainly their guardians or those who administrate their trusts,” Valliere said. “And if somebody is willing to take advantage of somebody with disabilities with regard to money in a way that hurts them, or in a sexual way, it would not at all surprise me that they would be willing to encourage them to choose death.”

Valliere was in Washington, D.C. on the week of his interview with the Washington Examiner in part to voice his support for a House resolution, introduced by seven Republicans and seven Democrats, that raises problems with assisted suicide.

But the Patient Rights Action Fund doesn’t only oppose assisted suicide. It also advocates for better end-of-life care.

The group supports a bill from Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon called the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act. The legislation boosts training for palliative care, a medical specialty that focuses on helping seriously ill patients relieve suffering at home by managing pain, receiving counseling for depression, and improving sleep.

“Using federal dollars to train people in hospice and palliative care is really important because people are dying poorly in this country,” Valliere said. “So, what’s the solution to that? Really good multidisciplinary palliative care that attends not only to patient’s physical pain, but their emotional and psychological suffering, and that of their family.”

Valliere received his undergraduate degree from Thomas Aquinas College, a Roman Catholic liberal arts school. He got his master’s in philosophy from Boston College. He declined to share whether he practices any particular religion, saying he doesn’t bring a specific worldview to his work focused on bringing people together for better end-of-life care.

“That kind of loving care, I think, is what we would all hope for at the end,” he said. “It’s not because somebody has a worldview that they would want that.”