Right now, Hillary Clinton has roughly a seven-point lead over Donald Trump in the head-to-head polls, but this shrinks to a five-point lead when voters are allowed to choose somebody else. Third-party candidates (especially Gary Johnson, the Libertarian, and Jill Stein, the Green) are combining for 11-13 percent of the vote in the latest polls. And from the looks of it, they are sampling disproportionately from would-be Clinton voters.

It’s fair to ask whether such a large share of voters will stick with third party candidates, or grudgingly migrate to Trump and Clinton. What does history tell us?

For starters, the logic of our electoral system cuts against third parties. French political scientist Maurice Duverger outlined a principle (since named for him) that electoral systems such as ours—winner take all, single member districts—tend to favor two-party systems. One reason is that voters prefer not to waste their votes, so third party candidates are punished, as voters feel obliged to choose between two, major parties.

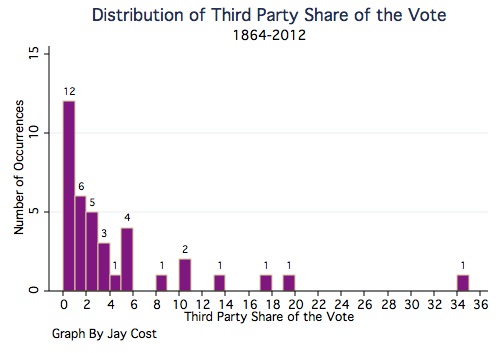

The rule is not ironclad, of course, but history demonstrates that third parties have had a rough go of it in our system. The following is a frequency graph that tracks how well third parties have done since 1864 (when the current Democratic-Republican divide stabilized). Each bar counts how many times third parties have gotten the corresponding share of the vote.

As you can see, the overwhelming majority of elections—23 out of 37—saw third party candidates get a combined share of less than 3 percent of the vote. And there have only been four cases in history when third parties have actually won as much as Johnson and Stein are now pulling—the elections of 1912, 1924, 1968, and 1992.

None of these elections corresponds very well to 2016. There were real ideological splits within the parties in 1912 and 1924, and in both cases high-profile politicians (former president Teddy Roosevelt in 1912 and Senator Robert LaFollette in 1924) led the insurgencies. The divide in 1968 was not so much ideological (in the typical left-right sense that we take for granted today), but a regional one, and the support for George Wallace (who himself was quite notorious) was concentrated mostly in the South. In 1992, Ross Perot was a media celebrity whose bid more closely resembles the Trump campaign than the Johnson or Stein candidacies.

Indeed, Johnson and Stein really have little in common with any of the third party candidates who managed such a hefty share of the vote. Johnson perhaps comes close to the John Anderson candidacy of 1980, but even then, Anderson had run in the primaries and was a more notable figure.

At one point in the early summer of 1980, Anderson was in a statistical tie with Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, according to the Gallup poll. As voters began to plug into the campaign, his numbers fell. A similar phenomenon happened to Ralph Nader in 2000. In many polls during that cycle, Nader was polling in the high single digits. His numbers sank as election day approached, and he underperformed almost all of the final polling estimates.

The cases of Anderson and Nader are consistent with what Duverger would predict: as voters really start to engage in the process, they become aware that only one of two candidates can realistically win, and most choose not to “waste” their vote. Again, this is not an ironclad law, just a tendency. And to counteract it, you usually need a substantial, counteracting force to push voters in the opposite direction—like a TR in 1912 or a Perot in 1992.

There is nothing about Johnson or Stein that is nearly so interesting. After all, the two of them ran in 2012, and combined they accounted for just 1.35 percent of the vote. The only significant force this cycle is the widespread disdain that voters have for the major-party candidates. People really dislike Trump and Clinton, so it is possible that they stick with Johnson and Stein. This would be unprecedented, but—weirdly enough—be typical of the 2016 campaign, which seems insistent on breaking every available precedent.

Unfortunately, then, the title question does not admit of an answer. Still, we can lay down a rough marker: When the debates begin, we should start to see voters abandoning Johnson and Stein, if indeed they ultimately do. That should be the point at which they begin to get serious about their choices, and recognize that the next president will either be Trump or Clinton. It won’t help Johnson or Stein that they’ll likely be excluded from the debates. On the other hand, if they continue to combine for more than 10 percent of the vote, that’s a good indication that a sizable quantum of voters are actually fed up enough to go third party.

My guess, for what it is worth, is that Johnson and Stein will combine for a larger-than-average share of the vote, but short of their current combined total. I’d expect them to win less than 10 percent, and would not be at all surprised if they won less than 5 percent. My hunch is that widespread disgust for Trump and Clinton will buoy their margins, but neither really offers much of an impressive reason to vote for them.