There’s an old truism in sports that says if you allow an underdog to hang around long enough, he just might win. Such has been the case with Donald Trump.

His candidacy was a novelty at first: A hubristic businessman and reality TV star running for president amid a large field of deeply qualified candidates.

Yet he polled near Jeb Bush at the top of most surveys upon his entrance into the race. He soon built a significant lead nationally and in some of the early primary states. And as we’ve seen from the votes in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada, his ability to establish himself months before the elections was decisive.

In the three most recent primary states for Republicans, Trump’s advantage among voters who decided their support more than a week before election day was overwhelming and insurmountable. It’s been said that Iowans and Granite Staters are typically late to pick a candidate, and that’s true: According to entrance and exit polls, roughly half of GOP voters in these states, as well as in South Carolina, made up their minds a week or less before the vote. But the people who determined their choice earlier have truly determined the direction of the presidential campaign.

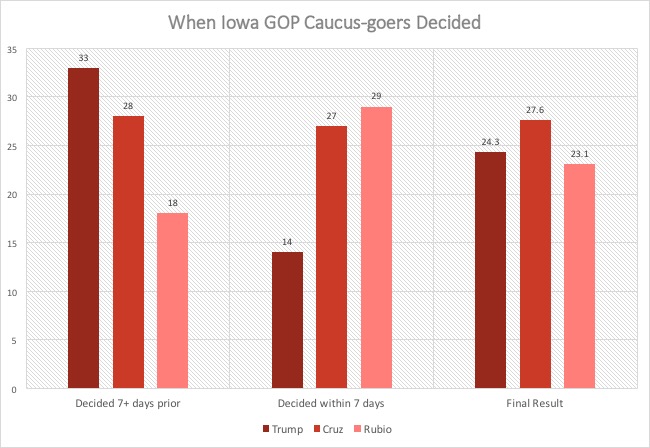

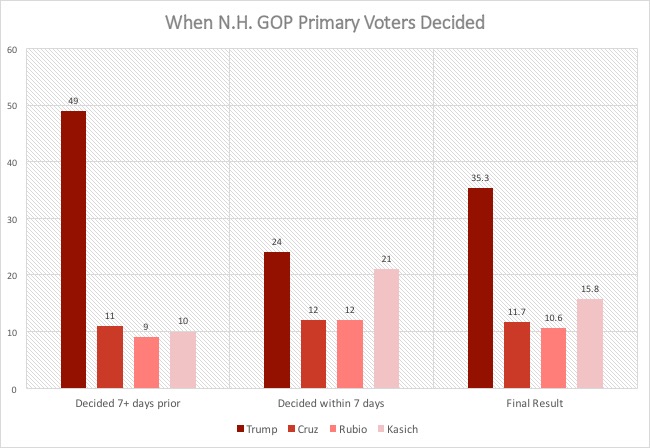

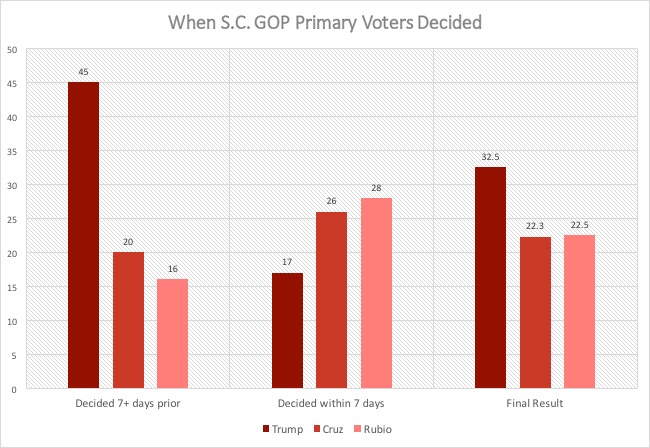

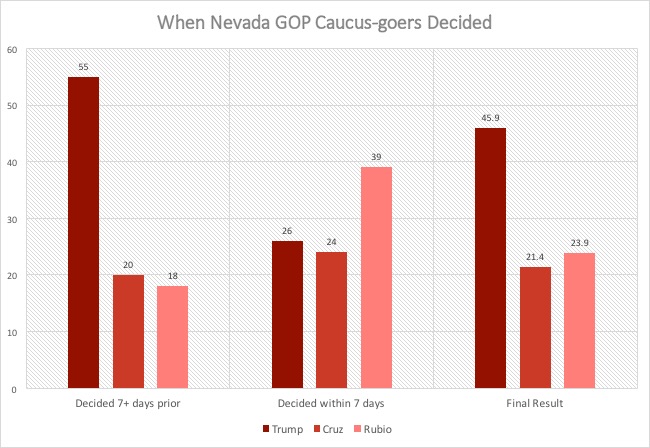

The following charts compare “early-deciding” and “late-deciding” voters in the first four primary states, with a week before election day as the cutoff separating the two categories. Notice the yawning gap between Trump and the rest of the field among the early-deciding voters — particularly in New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada — and how it has blunted the momentum of candidates like Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, who have fared well among the voters procrastinating their decision.

In Iowa, Cruz managed to minimize the gap, helping deliver him a narrow victory.

In New Hampshire, however, Trump was a juggernaut early, precluding any challenger from making a serious run at first place.

It was the same story in South Carolina, even though Cruz and Rubio both did comparatively well among late-deciding voters.

And in Nevada, where 7 out of every 10 caucus goers reported making their choice more than a week before the vote, Trump took more than half of early-deciding voters, rendering Rubio’s dominance of the other group meaningless.

There are implications and lessons from these data. First, it’s evident that Trump has amassed a significant number of committed backers who don’t waffle on their preference, which dampens previous speculation that the businessman could have “soft” support. Trump’s core supporters are an entrenched group. As he began his campaign, they liked what they saw, and they’ve stuck by him. Now that he’s proven his formidability, there’s little reason for this to change, barring a development in the race that breaks his immunity to errors and political liabilities.

The lessons are these: Trump was not damaged early in the campaign, and the failure of his rivals to dent him when he was not regarded as a serious candidate could determine the Republican primary. The only outside group to spend big against Trump in 2015 was the Club for Growth, as data enthusiast Max Galka graphed here. The only one of Trump’s rivals to challenge him in public with any urgency before voting officially started was Jeb Bush. Ted Cruz came around only when Trump vilified him after the Iowa caucuses. In the meantime, Rubio and Cruz are going after each other. And the big money is afraid to go after Trump.

The dollars may have been more useful several months ago, anyway.