There’s always a catch. This season the NFL will have more completed passes, thanks to new, receiver-friendly definitions in the catch/no catch rule. But there’s always a catch!

The Steelers’ overturned touchdown reception in the closing seconds of a regular season game versus New England late last year; the Dez Bryant no-catch ruling in the 2015 playoffs versus Green Bay; these and many other no-catch rulings that have driven football aficionados crazy would be receptions in the coming season under a new rule.

The new rule says control the ball and get your feet down. That’s simpler than the old rule and deletes the “survive the ground” nonsense that drove everyone to distraction. If the ball jostles on contact with the ground, it’s still a reception. The new rule won unanimous support at an owner’s meeting last winter and is a clear improvement over the old rule.

The catch is that there will be more receptions—but also more turnovers. Pass plays that in recent seasons have been signaled incompletions will be signaled completions followed by fumbles in 2018. TMQ suspects this will drive spectators just as crazy as did the old catch/no catch dispute. A receiver will snatch a pass, stumble to the turf, and the ball will carom loose and be recovered by a defender; spectators and announcers will assume the play is an incompletion; and the zebras will instead award possession to the defense.

Perhaps the football world will decide that more catches plus more fumbles equals more fun. Tuesday Morning Quarterback suspects that by the conclusion of the 2018 season, the catch/no catch rule will go back to the drawing board yet again.

So allow me to propose a solution to a problem that hasn’t happened yet: how to fix the new catch rule. Adopt the standard that applies to running plays, namely, that the ground cannot cause a fumble. On a rushing play, if the runner hits the turf and the ball pops loose, the down is simply over. This season, if the receiver makes a catch and immediately goes down with the ball popping loose because of the ground, the play will remain live. Switching to the “ground-cannot-cause” standard should eliminate this problem. (While we’re messing with the catch, let’s revise the language used to describe receptions. On a leaping reception, announcers often say, “He caught the ball at its highest point.” The highest point of the pass is far above the level any person can leap to. What announcers mean is, “The receiver outjumped the defender.” So say that!)

Other new NFL rules for 2018 include stricter prohibitions against deliberate helmet-to-helmet hits; eliminating meaningless extra-point tries after time expires; and allowing the NFL command center to order a player ejected from a game in progress even if officials on the scene did not.

The new standard against vicious hits is an excellent idea but may prove difficult to enforce. In team sports, athletes always want certainty regarding what the officials will allow or not allow. There’s likely to be considerable uncertainty with the new helmet-to-helmet standard. But just read this 546-word NFL fact sheet about the rule. Players can keep all that in their heads at game speed, can’t they?

The no-meaningless-PAT rule may sound trivial—who cares about the meaningless try? Bettors, that’s who. As states begin to legalize wagering on professional sports, and as the NFL draws closer to throwing its arms around Las Vegas, the point spread will get more attention. By eliminating the meaningless PAT, the NFL has moved to eliminate one opportunity for manipulation of the spread. In and of itself that sounds good, but TMQ thinks the league is clearing the decks before saying that gambling on the NFL is okay. More on that next week.

As for the new remote expulsion rule, it’s a fine advance, even if, as may be likely, it’s rarely invoked.

At the 2009 Super Bowl that squared Pittsburgh versus Arizona, James Harrison, a dirty player, punched a Cardinals player; he was flagged but not tossed, as should have occurred. Harrison would go on to make a key tackle in the closing seconds to help the Steelers preserve a four-point victory. Had Harrison been ejected, the outcome might have been different.

Probably the new rule will need lead only to a couple of ejections on orders from league headquarters, and dirty play will decline.

Also, in 2018 a head-first slide will be treated the same as a feet-first slide: The ball will be dead at the point where the slide begins. Presumably this will discourage quarterbacks (or anyone “giving himself up”) from sliding head-first hoping to gain an extra yard, creating avoidable risk of brain trauma, or from causing a helmet-to-helmet contact penalty that is really the fault of the offense, not the defense.

This new slide rule is a change in the NFL officiating manual (which is slightly different from the rulebook) and may have more impact than meets the eye. In recent seasons, quarterbacks leaping through the air head-first have gotten credit for their advance till they hit the ground. Now, the ball will be dead where the leap began. This season, it may not be long till some scrambling quarterback reaches the 2-yard line and dives forward into the end zone. The crowd will go wild thinking touchdown, but the ball will be spotted at the 2.

There is talk that the mysterious NFL officiating-standards—not the rulebook, which anyone can inspect at a snappy 89 pages, but the manual that officials are supposed to employ to determine judgment calls—will suggest fewer replay reviews and reversals this season. TMQ has long maintained that calls on the field should only be reversed if they’re obviously wrong. When officials look at a replay over and over and over again, then it’s evidently not obvious what happened—so just let the call on the field stand.

Tuesday Morning Quarterback maintains replays could be simplified, and sped up, by a double-blind review conducted by an official who does not know what was signaled on the field. The reviewer would rule solely on whether the result of the play is “clear and obvious.” Depending on how this season’s replay situation unfolds, I may return to this proposal.

In other football news, this season the Rams and Saints will field male cheerleaders. Your columnist has been saying for years that if there are to be buff cheer-babes flouncing along the sidelines, there should be studly cheer-hunks as well. “With scantily clad cheer-babes part of marketing throughout the NFL, and increasing women’s interest in football, TMQ continues to believe the league is missing an opportunity by not fielding shirtless male cheer-hunks” – TMQ in a 2011 column that noted Woodrow Wilson spent his college autumn Saturdays as a male cheerleader.

With more cheer-hunks arriving (Baltimore already has them), Tuesday Morning Quarterback proposes this sideline strutting standard: Whenever the women go two-piece, the men should go shirtless.

Now, for TMQ’s NFC preview:

Arizona. Carson Palmer has hung his cleats by the fireplace and retired from athletics. Through a 16-year career that began as the first overall choice of the NFL draft, he threw an impressive 294 touchdown passes. But perennially, Palmer flamed out after New Year’s Day. He won just one postseason contest in that long career. In the month of January, Palmer was 1-8.

Considering TMQ declared pre-draft that Josh Rosen was the best rookie quarterback available, I’ll be rooting for him with the Cardinals. Of course if Rosen falters I will invent some bogus excuse to claim I predicted he would struggle.

For the moment, the Cactus Wrens’ signal-caller is Sam Bradford, signed to a free-agent deal that will pay him nearly as much in 2018 as will be received by Drew Brees, even though Bradford is an oft-injured gent who has been shown the door by three consecutive NFL teams.

New Arizona head coach Steve Wilks will begin the season as the NFL’s least-known head coach. Will he end the season the same way? Wilks did a solid job as defensive coordinator of the Carolina Panthers. In 22 years as a football coach, Wilks has held 15 jobs. This doesn’t make him weird—in the nomadic world of football coaching, it makes him normal.

Last season the Cardinals were lower-tier pretty much across the board: 19th in points allowed, 25th in points scored. Their leading rusher barely outgained a quarterback, Tyrod Taylor. The great wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald is back, but he’s slowing down with age—last season he averaged only 10.6 yards per reception and ran many hitch screens that seemed designed to pad his stats.

With a rookie quarterback, a rookie head coach, and an overall dearth of talent, it could be a long season for this franchise that just two years ago reached the NFC title game.

Atlanta. Kirk Cousins, who has never quarterbacked a playoff win, was at one juncture during the offseason the highest-paid NFL player ever, judged by guarantees. Guarantees are the only portion of a professional football contract that you can take to the bank. (For example, in early 2017 the Colts signed Johnathan Hankins to a “three-year, $30-million” contract that lasted only one year and paid $10 million, which was the guarantee; Hankins currently is OOF, for “out of football.”) Cousins’s deal had $84 million in guarantees, which is ho-hum by NBA standards but spectacular for the NFL.

Then Matt Ryan surpassed Cousins with a deal that contains a $100-million guarantee. On paper the deal will pay Ryan $28 million in 2023, when he will be 38 years old. I’ve got five bucks that says he will be unhappy with his contract well before then.

Considering that the Falcons have a flashy passing attack featuring Julio Jones, touts were surprised when Atlanta used its first draft choice on a wide receiver, Calvin Ridley. But the team had 30 “clean drops” last regular season: passes that hit the receiver right in the hands in stride but were dropped like a live ferret. That number was worst in league. The season culminated with Atlanta losing to the Eagles in the playoffs on a key Jones clean-drop in the end zone.

Since the Falcons are not in Green Bay’s division, in theory they should face the Packers every fourth year. Instead this year’s sked includes the Falcons’ fourth game against the Packers in three years. But Atlanta faithful will not be complaining, as their heroes are on a 3-0 streak in this rivalry.

In the 2016 season, Atlanta came within a few minutes of a Super Bowl win. In the 2017 season, Atlanta came within a fourth-quarter dropped pass of returning to the NFC title game. Considering the latter defeat was to Philadelphia, for consecutive campaigns the Falcons’ season has built up to a fourth quarter nail-bitter playoff loss to that season’s Super Bowl champion. So do not count the Falcons out, especially since they have the incentive of reaching the Super Bowl on their home field, in Atlanta, on February 3.

Carolina. New Panthers owner David Tepper paid an NFL-record $2.2 billion for the team and will get about $500 million in tax breaks, which makes his true cost around $2 billion, with around $200 million covered by the public. See this revealing article, by Katherine Peralta, spelling out how NFL owners can claim write-offs by pretending their franchises are depreciating (declining in value) even as each new NFL team sale sets a record.

After making his taxpayer-subsidized purchase, Tepper’s team will play in a stadium that is extensively subsidized by Carolina taxpayers. Like with so many other NFL teams, the owner is a billionaire receiving corporate welfare. How long till Tepper favors the public with a lecture about his risk-taking entrepreneurial virtues? How many North Carolina politicians wag-wag-wag their fingers about how entitlements to the old and sick must be reduced?

In 2016, the Panthers suffered a Super Bowl hangover from losing to Denver in the prior season’s finale. In 2017 they were back to normal except when facing the Saints: Carolina finished the season 0-3 versus New Orleans but 11-3 versus all other teams.

In 2017, Cam Newton seemed like a college kid again, which normally would be a good thing, but in this case was not: He ran the ball too often, leading the team in rushing with 754 yards. The Panthers had just employed their first-round draft pick on a tailback, Christian McCaffrey. He rushed 117 times—Newton rushed 139 times. That’s right: The quarterback ran more often than the first-round-drafted tailback. This is not good overall, and really not good in the contemporary pass-wacky NFL.

When Newton did drop back to pass, the results were not bonnie, as a Scot would say. (There’s a Scotland TMQ item upcoming.) the Panthers finished 28th overall for passing offense, a terrible stat for a team with a quarterback chosen first overall. In the playoffs at New Orleans, trailing by five points, the Cats reached 1st-and-10 on the Saints 21 with 41 seconds remaining and were seemingly poised for victory. Instead, Carolina went incompletion, intentional grounding, incompletion, sack—season over.

It’s an indicator of how quickly fates can change in team sports that the same New Orleans defense that staged this high-pressure, last-minute stand would, the following week at Minneapolis, allow the Vikings to go the length of the field to win as the clock expired. But from the Panthers’ standpoint, the final 41 seconds of last season were a study in frustration, which has pretty much been the team’s theme since the Super Bowl comedown.

Father-son fun facts: Panthers backup quarterback Garrett Gilbert is one of football’s leading vagabonds. An Austin prep star who complied a hard-to-believe 12,537 yards in high school, Gilbert has since been with a total of seven Division 1 and NFL programs, searching for a home. He threw four interceptions in the 2010 national championship game that the University of Texas lost to Alabama and basically still hasn’t recovered. (Neither has Longhorns football.) Give him credit for refusing to quit!

Garrett’s dad Gale Gilbert also was a longtime backup quarterback in the NFL and holds one of the fun-fact goofy distinctions in sports lore: the only player ever to lose the Super Bowl in five consecutive years. Gale was the scout-team quarterback when the Bills went woe-for-four, then on the wrong end of the big game again the following year as clip-board-holder for the Chargers.

How Long Would the Kessel Run Take at Warp 6? NASA recently launched the Parker solar probe, which will explore the photosphere of the sun. At a peak speed of about 432,000 miles per hour, Parker will be by far the fastest manmade object. That’s fast enough to reach Mars in only a few days. (Estimates to follow take into account only peak velocity, not the time required for acceleration and braking—more on that later.) But as fast as 432,000 mph sounds, it’s only 0.06 percent of the speed of light. At the maximum zing of the Parker probe, it would take around 7,000 years to reach the star system closest to ours.

Numbers like that raise the serious question of how to comprehend the immensity of interstellar distance. They also raise a fun question: How fast are things going in science fiction?

In Star Wars, very-long-distance travel is depicted as nearly instantaneous. Ships pop into hyperspace, then pop out at the destination. No acceleration or braking complications here, since there doesn’t seem to be any speeding up or slowing down. Occasionally we see characters talking onboard faster-than-light battlecruisers as blurry stars go by in the distance. How could you see blurry stars if the ships are moving far faster than the light emitted by the stars? Of course the physics of what might happen under impossible circumstances are, to say the least, conjectural. Anyway, Star Wars offers little hint on how fast stuff is moving, other than really, really fast.

The latest Star Wars movie, Solo, does offer some mumbo-jumbo about why Han Solo said the Millennium Falcon made the Kessel Run in “12 parsecs,” which are a unit of distance, not of time. Perhaps the physics of FTL travel in that faraway Star Wars galaxy depend on how many sequels are greenlit.

Then there’s the ever-confusing warp numbers of Star Trek. One of the first episodes of Star Trek: The Original Series, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” takes place at the rim of the galaxy, which the Enterprise is said to have reached in a few days. The rim of the galaxy is about 25,000 light years from Earth, making top speed of the Enterprise during this journey about 2.5 million times the speed of light. But in the series Star Trek Voyager, which is set about 100 years after Captain Kirk, the Voyager is stranded 70,000 light years away, where coming home is said to require 75 years at maximum warp. That makes the top speed of Voyager about 1,000 times the speed of light: less than one percent of top speed of Starfleet vessels from a century before.

In your columnist’s favorite Star Trek episode, “The Paradise Syndrome,” first broadcast in 1968, the Enterprise needs a few hours at warp 9 to travel the distance an asteroid will move in 59 days. Since no asteroid moves at more than a minute fraction of light speed, that makes warp nine much slower than the speed of light.

On Star Trek: The Next Generation (the Picard-and-Data version, set about a century after Kirk and Spock), an Enterprise shuttlecraft travels two light years in 20 minutes. That’s about 50,000 times the speed of light, or 50 times faster than the Voyager, which is said to be more advanced than the Enterprise of that time.

Then there’s the new iteration, Star Trek Discovery, which is a prequel, happening 10 years before Kirk and Spock, and a century before Picard and Voyager’s Captain Janeway. The MacGuffin of Discovery’s first season is the invention of a stardrive that can move a ship “90 light years in 1.3 seconds.” This is about 25 billion times the speed of light! At 25 billion times the speed of light, crossing from from one edge of the Milky Way to the other—an unthinkable expanse—would take a couple of minutes. By way of comparison, the Parker solar probe would need 175 million years to cross the Milky Way.

I won’t tell you how the first season of Star Trek Discovery turns out, except to add that in the Star Trek mythology, Starfleet’s best ship more than a century later, the Voyager, has 0.000004 percent of the peak speed of the Discovery. Oh—and Discovery’s drive system is, for intents and purposes, actually powered by a MacGuffin!

As for acceleration and braking, the higher the top speed, the larger a consideration acceleration and braking become, unless it’s all instantaneous, like in Star Wars. Because the Parker solar probe will never land anywhere, it only has to speed up. If it also had to touch down, shedding speed would be central to the mission profile. Should there ever be a manned Mars mission employing chemical rockets of today’s basic type, braking would be as important as acceleration and would consume a lot of time and fuel, adding duration to the journey while subtracting crew or payload.

In sci-fi this isn’t a constraint. For all the nuttiness of Star Wars and Star Trek—telekinesis and precognition, teleportation by disassembling living molecules, “tea, Earl Gray, hot” made of pure energy—my favorite scene is when a Starfleet ship captain commands, “All stop!” The vessel goes in a snap of the fingers from far faster than the speed of light to full stop.

Star Trek Discovery fun facts: Weapons hits on the hull still cause electrical fires on the bridge; tiny, cramped crawlways are still the only access to critical buttons; prison guards still bring firearms into cells, where prisoners easily snatch them away; security officers the audience has never seen before still are killed in the first scene after they come onscreen; intruders still need mere seconds to seize total control of a Starfleet vessel, easily done from any computer terminal; the main viewscreen on the bridge still makes blinding flashes that cause the crew to cover their eyes, though it would seem an electronic viewer (it’s not a window) would be set not to generate harmful degrees of brightness; away teams still beam down to mysterious uncharted planets on foot with only small arms and radios, rather than sending drones first. At least this is realistic: 230 years into the future, there is still no cure for snoring.

Chicago. Undrafted tight end Trey Burton, who’s started just five games in four years in the NFL, signed with the Bears during the offseason for $18 million guaranteed, which is major money for a career backup. But then Burton has thrown a touchdown pass in the Super Bowl, which only two previous Bears, Jim McMahon and Rex Grossman, have done. Who’s Burton? The guy who launched the end-around touchdown toss to Nick Foles on fourth-and-goal.

Let’s hope the Burton deal proves out, since the Bears have been making numerous free agent gaffes. During the 2017 offseason Chicago gave big contracts to Mike Glennon and Markus Wheaton, both of whom are already gone, as the Eagles (the band, not the team) would say. Released by the Bears, Wheaton is now with the Eagles (the team, not the band), and if he plays well in 2018, the Bears’ player-personnel reputation will sink even further.

General manager Ryan Pace also botched the money-management aspect of the NFL when it came to cornerback Kyle Fuller. Rather than negotiate with Fuller in good faith, Pace out-thought himself, then ended up having to match a Green Bay contract offer that contained a salary-cap time bomb. The move was clever for the Packers: They’d either get a young star without having to trade a draft choice, or they’d force a divisional rival to overspend. To top off these follies, Chicago extended a megabucks contract to Allen Robinson, who missed 2017 with a severe injury.

Just to prove it was no fluke, Pace engaged in a lengthy food-fight dispute with the agent for top draft choice Roquan Smith, who ended up being the final member of the 2018 NFL draft class to sign. The dispute concerned whether future-years guaranteed payments would be voided should Smith be arrested or otherwise land in hot water. If the Chicago Bears are so worried about this that they are willing to mess up their prize rookie’s first season, then don’t have a spat with an agent—change the culture of football.

Bears stat not for the faint of heart: Mitch Trubisky started 12 games for the Bears in 2017 and threw only seven touchdown passes.

City of Tampa. There’s under the radar, there’s stealth technology, there’s the Romulan cloaking device—and then there’s the 2017 Tampa Buccaneers. Did you see any of its games? Hear anyone mention this team in any context? Can you name any starter other than Jameis Winston? And if you named Winston, probably the reason you knew his name wasn’t good.

Few teams in recent years have engendered as little interest as the 2017 Buccaneers. City of Tampa was last in overall defense and last in passing defense; the Bucs surrendered 38 points to a Cardinals team that would finish the season near the bottom for scoring. Determined to rise to average on defense, in the offseason Tampa traded for defensive end Jason Pierre-Paul, signed defensive end Vinny Curry, used its first draft choice on defensive tackle Vita Vea, and then, after trading down to add picks, used its next two choices on defensive backs.

Maybe this will help, but TMQ thinks little will change until the Buccaneers replace their utt-bugly uniforms. Even Tampa fans hate the unis. “Looks good, plays good” is the sports maxim. Did you catch Golden State’s gorgeous gray-and-yellow The Town unis? The Warriors looked good, played good. In Tampa it’s looks bad, plays bad.

During the suspension of Winston, perpetual vagabond Ryan Fitzpatrick will command the Bucs’ huddle. Fitzpatrick quarterbacked for seven NFL clubs and posted an impressive 119 career starts, yet has only one winning season in the pros. None of this matters, because at Harvard, he beat Yale.

Dallas. Weren’t the Boys supposed to be the next monster team? Since kickoff of a home postseason game versus the Packers, Dallas is 9-8 and last season posted just won quality victory, over playoff-bound Kansas City. (The Cowboys defeated Philadelphia on New Year’s Eve, but the Eagles had locked up home field and were resting starters.)

Yeah, sure, there was a secret conspiracy to keep Ezekiel Elliott off the field—that was the excuse from Boys’ boosters. I was recently in Dublin, where a guy at a pub said, “The pedophile priests were sleeper agents who were put into the church to discredit it.” Anytime you’re calling on conspiracies to explain failure, you’re in deep.

As for this season, Jerry Jones told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that he trusts Elliott “as much as he trusts himself”—which may be true! Fun fact: to Texans the venerable Star-Telegram is known as the Startle-Gram.

At least the Dez Bryant nonsense is over. Dallas ended up waiving Bryant because nobody wanted his contract: Any team acquiring Dez in a trade would have acquired the obligation to pay him $25 million. Or was the real reason that nobody wanted Bryant the player? He brings his own sideshow, and unlike the much-lamented Ringling Brothers, his sideshow is not entertaining. That the Cowboys failed to deal with the Bryant sideshow hurt them more last season than the Elliott suspension.

Bryant caught 58 percent of the balls thrown to him during his time in Dallas, versus Antonio Brown catching 66 percent of balls thrown to him in Pittsburgh. At Brown’s rate, Dez would have caught 69 more passes for the Boys—nearly an entire extra season of receptions. Why would any team want a prima-donna who whines nonstop, gets high pay, and then drops passes? Why did Dallas tolerate him so long?

Detroit. Ah, for Thanksgiving Day of 2013. Donald Trump was just a cheesy reality-show host. Paul Manafort was just a yes-man for a Ukrainian tyrant. Robert Mueller had retired from the FBI and gone to teach a yawn-inducing seminar at Stanford. Hillary Clinton still had 33,000 emails about yoga poses and muffin recipes on her private server. And on Thanksgiving Day 2013, the Detroit Lions had a 100-yard rusher.

They haven’t since. To go more than four seasons—2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017—without a 100-yard rusher is quite the feat, even in today’s pass-wacky NFL. Just to prove it was no fluke, last season the Lions finished last in rushing with barely half the yards-per-game of the leader, Jacksonville.

Passing success, especially average gain per attempt, is more important than rushing prowess. But the two most recent Super Bowl entrants both were solid on the ground, the Eagles finishing third and the Patriots tenth. Last season, nine of the top 10 teams for rushing reached the playoffs.

Detroit’s inability to run the ball isn’t just a quirk. It’s a core reason the Lions have not won a postseason game under megabucks first-overall-draft-choice Matt Stafford. For that matter the Lions have not won a postseason game since the elder George Bush was president.

Presumably new head coach Matt Patricia understands Detroit must be able to pick up first downs on the ground and will revamp the Lions’ Arena-League-style offense. Among Patricia’s first moves was to sign power back LeGarrette Blount. Like Dez Bryant, Blount has a way of wearing out his welcome. He was kicked off his college team and has been shown the door six times in the NFL, including twice by New England. But he carries the football into the end zone. In the last two seasons, Blount has 25 rushing touchdowns. That’s more than the entire Detroit Lions team in the same period.

In 2017 the megabucks Stafford tied for league worst with seven lost fumbles. Tom Brady played in more games than Stafford and lost fewer than half as many fumbles. Russell Wilson was hit hard a lot in 2017 and lost fewer than half as many fumbles. Stafford is often carless with mechanics, the ball rolling around on the ground being the result. Patricia will change him or bench him, regardless of his paycheck.

Green Bay. During the offseason, Aaron Rodgers met the Dalai Lama. Perhaps this autumn Rodgers will float cross-legged above the huddle. (My neighborhood gym is call-button 2 in the elevator from the car park. There’s a yoga studio at button 3. When the elevator is full of patrons with yoga mats slung over their shoulders on the way to the studio I think, “Shouldn’t they just ascend to floor 3?”)

The 2017 campaign was essentially erased from the Packers’ record books and repressed from fans’ memories, as the injury to the team’s frontman meant a generation of Wisconsin fans who had seen nobody but Brett Favre and Rodgers at quarterback suddenly were watching Brett Hundley and Joe Callahan. Under Rodgers, Green Bay has been a high-scoring club; without him the Packers were shut out twice. Presumably the team expects Rodgers to regain his form, as Green Bay did not draft a quarterback of the future—though the Packers did trade down to acquire an extra 2019 first-round selection, in case a top young signal-caller is needed a year from now.

Jordy Nelson, long Rodgers’s favorite target, was shown the door in free agency. Touts expressed surprised that Rodgers held his tongue about this move. TMQ suspects the reason was that Rodgers knows every salary cap dollar saved is a dollar that can go into the max contract the Green Bay quarterback seeks.

Cap space not spent on Nelson was also redirected to signing Jimmy Graham, who last season caught 10 red-zone touchdown passes—not bad considering that last season he played in Seattle’s sputtering offense. Graham once was seen by touts as unstoppable, but with the Seahawks in 2017 he struggled. Then again, so did the whole team. Much of Green Bay’s 2018 outcome will depend on how Graham performs.

At the Weekly Standard there is no ideological litmus test but a rigid sports requirement that one root for the Packers. The Standard’s many on-staff Wisconsin faithful may not want to hear this, but Tuesday Morning Quarterback thinks Green Bay has entered the downslope of a talent cycle. Titletown may be in for hard times. Perhaps that extra high pick in 2019 will begin the next up cycle.

Green Bay and the Seahawks, who have played some monster matchups in recent years—their 2015 NFC title pairing was fascinating in both athletic performance and tactics—both may be pushing the ground-floor call button in the standings elevator this season.

Sked note: Pack faithful can breathe easy that this season’s Bills-Packers tilt is in Wisconsin. The Packers have never won a game in Buffalo.

Jersey/A. The G-Persons have two Lombardi trophies since 2008 began, which only New England can match. But Jersey/A has not won a playoff contest since its 2012 Super Bowl victory. Considering the Giants’ face-painted crowd goes into hysteria mode if their charges do not win every single game by 50 points, there’s a local sense of panic surrounding this franchise, though arguably only New England is more accomplished in the NFL recently than the Giants.

The G-Persons had major offensive line issues last year. In a puzzling move, Santa Clara broke the bank to sign away Jersey/A center Weston Richburg, though Richburg was coming off a so-so season. This signing helped the Giants, who were able to invest the salary cap savings in acquiring left tackle Nate Solder, one of the league’s best linemen. (Solder note: In a classy move, he took out an ad thanking Patriots fans for cheering for him, and the ad wasn’t under a Russian-trolls tab at Facebook—it was in a traditional print edition of the Boston Globe.) Jersey/A used its second-round draft choice, #34 overall, on guard Will Hernandez. Assuming the blocking improves, as is likely, Eli Manning suddenly will look young again.

Jason Pierre-Paul and his negative energy field are gone; Saquon Barkley is added. When TMQ looks at Barkley he sees Marshall Faulk. If Evan Engram, the team’s first-round choice in 2017, progresses as a sophomore—young tight ends often struggle because the pro position is so different from the way tight ends play in college—the additions of blockers and Barkley, plus the development of a tall, fast tight end, could give Jersey/A power on offense.

Though the media attention went last season to quarterback melodrama and the incompetence of then-coach Ben McAdoo, the red flag was on defense, where the Giants dropped from second against points in 2016 to 27th in 2017. If the Giants’ defense can improve—which won’t be hard, since it was ranked 31st last season against yards—the crowd may break out the face paint.

Jersey/A invested a 2019 third-round choice in cornerback Sam Beal during one of the league’s intermittent supplemental drafts. Beal is already hurt and out until next season. Of course, most injuries are just random luck. But the supplemental draft is viewed by many touts as cursed, and this is the latest example.

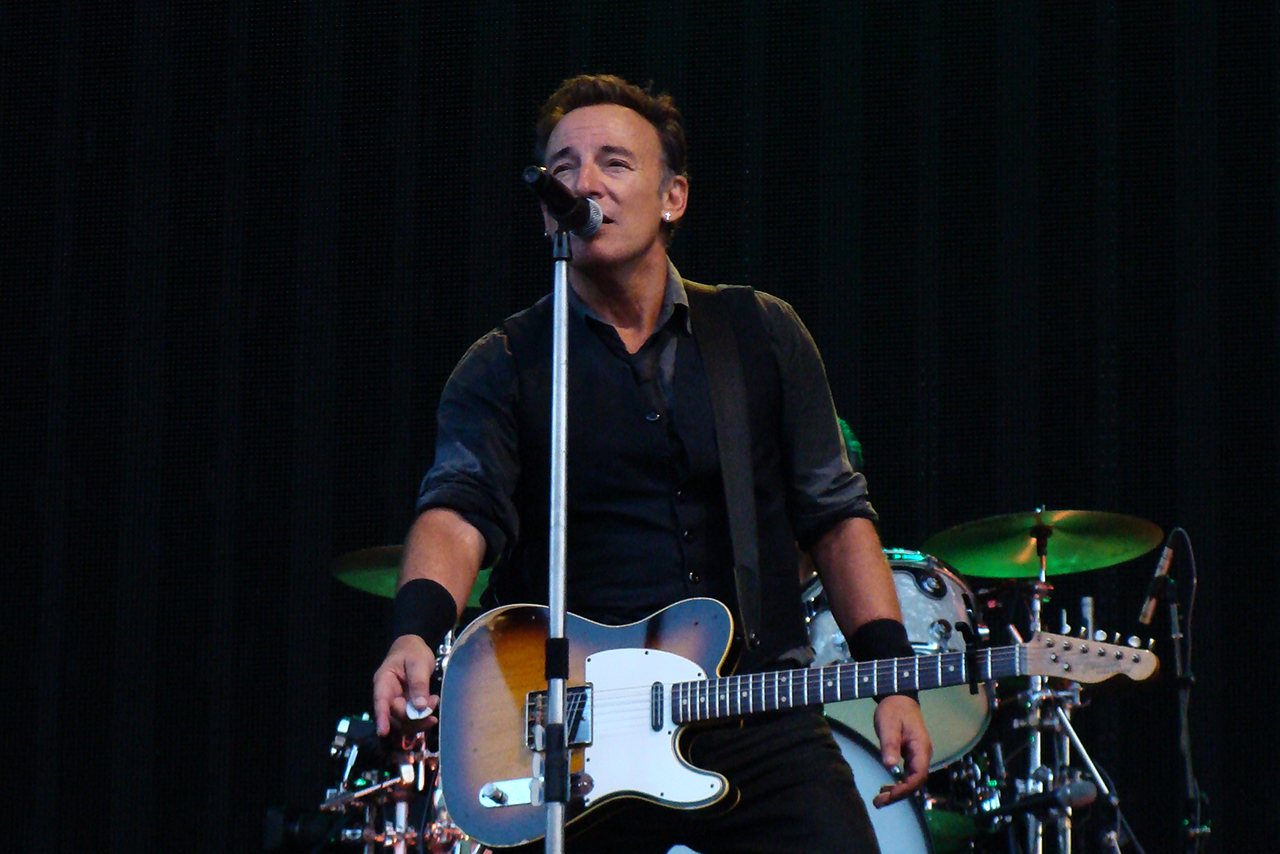

Both Jersey teams perform at MetLife Stadium, which turns blue for the Giants and green for the Jets. The stadium is in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Tuesday Morning Quarterback thinks the town should change its name to The Swamps of Jersey (factually accurate, plus tourism appeal for Springsteen fans), while the stadium should change its name to Somewhere, which reflects the New York-New Jersey confusion (plus has a nice postmodern ring).

Suppose these changes occurred. Then when a broadcast begins the announcer could say, “Hello everybody and welcome to today’s game from Somewhere, in The Swamps of Jersey.”

LA/A. The Rams went from the league’s lowest-scoring team, at 14 points per game in 2016, to its highest-scoring, at 30 points per game in 2017. Over a single season, more than doubling average points scored—that’s none too shabby. But then LA/A wheezed out in its playoff contest at home, posting just 13 points. So were they a flash in the pan?

This team has lots of roster turmoil even by the standards of the NFL, and that continued during the current offseason. Out are Robert Quinn, Trumaine Johnson, and Sammy Watkins; in are Ndamukong Suh, Aqib Talib, and Marcus Peters. Suh got a one-year deal, what agents call a “prove it” offer. The Dolphins were deeply disappointed in Suh’s lack of effort—as the 1990s draftnik Joel Buchsbaum liked to say, “Looks like Tarzan, plays like Jane”—and cut him basically on the day his final guaranteed payment conveyed. What are the odds the Rams will be any happier?

In recent months the Rams have conferred monster contract extensions on Brandin Cooks, Todd Gurley, and Rob Havenstein, all good players yet none with an expiring deal. But Aaron Donald, the Rams’ best player and among the top athletes in pro sports, remains in a contract impasse. LA/A could have bound Gurley for three years for about $25 million by holding him to his existing contract then using the franchise tag later. Instead the team inked him at more than $40 million guaranteed, while putting off money for Donald. Maybe such contract maneuvers will pan out, but they seem puzzling.

Early in the season the Rams have three straight in their building, followed by three straight on the road. Considering LA/A averaged just 63,392 fans in attendance last year despite a playoff run—good for 26th out of 32 teams—the Rams may perform before larger crowds on the road than at home.

Fun fact: last season both Los Angeles NFL franchises combined to average 88,727 tickets sold—less than the Dallas Cowboys alone drew, at 92,721.

Minnesota. The Jaguars and Vikings reached their conference title rounds largely on the strength of being ranked one-two in pass defense. Then both got torched. Jacksonville at least played a close game at New England; Minnesota was blown off the field in Philadelphia, 38-7. The collapse of the Minnesota secondary was total, as if the Vikes forgot how to play football. Minnesota allowed Nick Foles (sure, a great story, but also a backup) to pass for 352 yards, three touchdowns, and no interceptions. In the aftermath, for the fourth time in the last seven years, Minnesota spent a first-round draft pick on a defensive back.

Last season’s Vikes came the closest any team has ever come to playing in the Super Bowl on their home field. Minnesota reached the conference title round; the furthest a team had ever advanced before a home-field Super Bowl was the divisionals. A Super Bowl at home would have been highly advantageous to the Vikings, but an NFC title game on the road proved too much. Minnesota would finish the season 8-1 at home and 6-3 on the road, with its home loss a close contest but blowout road losses at Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. On the season, the Vikings won only one road game against a team that would reach the playoffs.

Explaining why he choose Minnesota in free agency, Kirk Cousins said, “The statistics show that it’s favorable to play indoors consistently.” That is true for individual athletes. For the team, Minnesota needs to improve outside the confines of its warm, friendly dome, with all the Thor-costumed guys, to avoid another Ragnarök. The Vikes team that was destroyed outdoors at Philly looked like an entirely different squad from the team that played so well indoors.

Via free agency, the Vikes essentially traded quarterbacks, Case Keenum for Cousins—tossing in the $84 million they guaranteed to Cousins, the first fully guaranteed large deal in NFL annals.

Cousins put up nice stats in a dysfunctional situation with the Potomac Drainage Basin Indigenous Persons. But his career record is 26-31-1; he’s never won a playoff game; for each of the last two seasons he’s looked terrible in money time, honking away winnable late-December games that Washington needed to reach the postseason. Mark Sanchez has a 41-37 career record with four playoff victories, and the sports world considers him a punchline. Cousins has a losing record with zero playoff wins, and a Brink’s truck parked at his door.

New Orleans. Last season the Boy Scouts pulled up one snap shy of reaching the NFC title contest, where they would have given the Eagles a better game than did Minnesota.

The Saints face a structural problem akin to that of the Vikings: They’re a lot better indoors in ideal conditions, but the playoffs are held in January, which often means going outdoors in bad weather. (The indoor-field Lions also face this problem but solve it by not making the playoffs.) In the postseason New Orleans is 6-5 indoors and 2-5 outdoors. More troubling, the Saints are 2-7 away from home in the playoffs. The one true road victory for New Orleans came at Philadelphia in the 2013-14 Wild Card—the other victory away from the Superdome was in the 2010 Super Bowl over Indianapolis. One road postseason victory in the history of a 51-year franchise is not much to write home about.

Lately the Saints have started slow, not getting serious about the season until autumn leaves begin to fall. In 2014, New Orleans opened 0-2; in 2015 and 2016, 0-3; in 2017, 0-2. Playing uphill after honking the first couple of games is not a formula for success, especially considering the NFL postseason format overvalues games within the division. That makes the Saints’ Week 3 date at division rival Atlanta the equivalent of a September playoff game.

Sophisticated observers (me, for example) lauded the Eagles for 4th-down success last season. New Orleans led the league in 4th-down conversion percentage, going for it 15 times and converting 12. Sean Payton may not be a 4th-down zealot like Doug Pederson, but he isn’t shy when the odds say to keep the kickers on the sideline.

Last season Drew Brees, now 39 years old, took every New Orleans snap at quarterback. Like 41-year-old Tom Brady, Brees can’t stand coming off the field, even late in games that are out of reach in either direction. Some stars who totally own their positions, such as Brady and Brees, never want to come out of the game even when, objectively, they should. Coaches should overrule their stars’ desires.

Aware of Brees’s age—if the city is to win another trophy with him, it’s now or never—the Saints traded away their 2019 first-round draft choice to reinforce for 2018. A year ago, they traded away their 2018 second-round choice to reinforce for 2017, and this almost worked. It’s now or never! Tomorrow will be too late!

Whatever happens, do not underestimate Brees’s ability to light it up. He has thrown for at least 5,000 yards in a season five times. All other quarterbacks in NFL history combined have thrown for 5,000 yards in a season a total of four times.

Philadelphia. In last season’s finale, the Eagles allowed the most offensive yards ever at the Super Bowl (613) and the most passing yards ever at the Super Bowl (505). So it’s hard to laud the Eagles’ defense. Yet at the end, when Philadelphia needed a stop, it got one. Leading 38-33 with 2:16 remaining, New England holding a time out, and facing comeback master Brady, the Eagles produced a sack-strip fumble recovery that effectively concluded the NFL season.

The scoreboard and clock situations were very similar to the endgame dynamic at the Super Bowl in 2008, when the Giants got a last-second sack (though no fumble) that effectively concluded the Patriots’ run at a 19-0 perfect finish.

On the sack-strip by the Eagles, defensive coordinator Jim Schwartz called the same front and pass rush combo that Jersey/A employed on the decisive down of 2008. Maybe that’s just a coincidence. But Schwartz is a smart guy (Georgetown University graduate) and a walking encyclopedia of defensive football. Your columnist wondered at the time if Schwartz recognized the Patriots were in the same situation they’d faced in 2008 and made the same call that vexed them once before.

For the Nesharim’s trophy season, most attention, including from this column, went to Doug Pederson’s willingness to go for it on 4th down. But the team’s defense should not be overlooked. In its first two postseason contests, Philadelphia surrendered a total of 17 points. Then Philadelphia got lit up at the Super Bowl—but the Patriots got lit up, too. Perhaps there was something in the water that day. Along the way to the trophy, Eagles defenders mounted this impressive accomplishment: The defense did not allow a score in the final two minutes of the fourth quarter for the entire season.

In addition to not allowing another 613-yard performance, the Philadelphia defense needs to get better on the road. Last season the Eagles gave up 12.4 points per game at home but allowed 25 away, which was above the league average for points allowed on road dates. Those first two postseason contests, in which the Eagles gave up only 17 total points, were at home. On the road in the Super Bowl, the Eagles let the scoreboard spin for 33 opponent points. This home-road variation is a leading indicator.

Philadelphia won the Super Bowl despite injuries that sidelined its starting quarterback, in whom the franchise had invested a king’s ransom, and stars Jordan Hicks and Jason Peters. Should all return to form, the team coming off a season-ending shower of green confetti will receive a major infusion of talent. Most Super Bowl winners are weakened the following season, by salary cap problems. If Wentz, Hicks, and Peters are all okay, the Eagles will be strengthened for their season of title defense.

Here’s a gripe from a purist. In recent seasons, as part of protecting quarterbacks, NFL officials have allowed offensive tackles to line up steadily farther off the line. Since the tackle must “rock back” to pass block, being off the line of scrimmage is an advantage. On half a dozen snaps of the Super Bowl, the Eagles’ offensive tackles were a full yard behind the center’s butt—see the third quarter touchdown pass to Corey Clement—which should have drawn flags.

The song is In olden days a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking / now anything goes. Just as in the Warriors-Cavs finals, when the NBA seemed to decide that anything goes with the supposedly-illegal moving screen, in the Super Bowl it was anything goes with the line of scrimmage. Let’s clean this up, please, zebras.

Defending champion fun fact: If, as expected, the Eagles start Jason Peters and Lane Johnson at offensive tackles, they will be starting two men who weren’t offensive linemen in high school. And here is the winter 2017 Reddit thread mocking the Eagles for wasting money on the washed-up Nick Foles.

Santa Clara. The good news for 49ers fans is that new face-of-the-franchise Jimmy Garoppolo has never lost a start; the bad news is that he has started seven times. After that modest body of work, Santa Clara signed Garoppolo to a megabucks deal that guarantees $90 million, while the league declared him one of the NFL’s Top 100 players. This gent who has never completed a full season, let alone started a postseason contest, gets significantly more pay than five-time Super Bowl victor Tom Brady and is being treated by the league as an accomplished star. He hasn’t done squadoosh!

Maybe everything will work out. But Tuesday Morning Quarterback has two words of warning for 49ers fans: Rob Johnson.

The Niners lost nine straight to open 2017, then won five straight to finish. Was this because Garoppolo took over? That was the reasoning behind the mega-contract and NFL-administered hype. But football is a team sport: It’s hard to view his seven touchdown passes over five starts as utterly transformative.

Just as TMQ is not yet sold on Garoppolo, TMQ is not yet sold on this team. An interesting roster battle is Jonathan Cooper versus Joshua Garnett. Both are recent number-one-drafted guards. It’s rare for guards to go in the first round; to have two recent first-round guards on the same roster is rarer. Cooper, chosen seventh overall in 2013, has been shown the door by the Cardinals, Patriots, Browns, and Cowboys. If he’s let go by the Niners, that’s all she wrote.

Garnett, chosen 28th overall in 2016, missed 2017 with an injury. He was one of two first-round picks in the year Chip Kelly administered the 49ers’ draft. During his stint running the Eagles, Kelly spent a first-round choice on Marcus Smith, who never started an NFL contest. If Garnett falls off the Niners depth chart, that would mean two first-round busts for Kelly in just four seasons of running NFL drafts—one of the many reasons Kelly is no longer in the NFL ranks.

The 49ers used a 2018 second-round pick on speed merchant Dante Pettis of UDub, vulgate for the University of Washington (as opposed to Washington University, which is in Missouri.) Last season the Official Wife of TMQ walked into the den just as the camera went closeup on Pettis preparing to field a punt. The closeup showed Pettis wore no knee protection; the nude knee is a trendy among speed merchants.

Me: “I don’t know why the coach doesn’t tell him to wear knee pads.”

(Pettis proceeds to run the punt back for a touchdown.)

Official Wife: “That’s why.”

Pettis posted an NCAA record nine punt runback touchdowns. He has a chance of being the next Devin Hester, which would be huge for Santa Clara.

Seattle. The Seahawks brought power-rushing back into fashion and used the run to win the 2014 Super Bowl, yet last season tied for last in the NFL with a mere four touchdowns on the ground. Many things have gone wrong for the Blue Men Group: injuries, dissention, reaching the downslope of a talent cycle. But it all starts with an inability to run the ball.

With 26 seconds remaining in the 2015 Super Bowl versus New England, Seattle had 2nd-and-goal on the Flying Elvii 1 and was holding a time out, so it could execute at least two plays. Seattle came in with the league’s top-rated rushing attack. All Seattle had to do was run straight up the middle and … well, you know the rest. The football gods have been punishing the Seahawks ever since, surely thinking, “I find your lack of faith disturbing” (the best book title in years).

From the start of Russell Wilson’s career, the Seahawks went on a 42-6 tear in Seattle. Then came November 2017, and since, they are 1-4 at home. Is it inability to run the ball, or is it losing at home, that has changed the Hawks? Pick your poison. Both are bad.

Since last season ended, the Seahawks lost Kam Chancellor to a career-concluding neck condition (Chancellor is smart not to press his luck) while offloading stars Richard Sherman, Michael Bennett, and Cliff Avril. Sherman was waived; Bennett was traded to the defending champion Eagles for a backup and a swap of late draft selections; Avril was put on waivers because of an injury. Developments like this show the magic is gone. Whatever mojo got Seattle the trophy in 2014 and within one run up the middle of the trophy again in 2015 no longer is present. And Seattle has already spent some 2019 draft choices.

Washington. R*dsk*ns president Bruce Allen can exhale: At long last he is rid of Kirk Cousins! Not Cousins the player, Cousins the symbol of management ineptitude.

To start the 2012 draft, Allen traded the sun, moon, and stars for Robert Griffin III, then departed New York City aboard Chainsaw Dan Snyder’s private jet. On the third day of that draft, head coach Mike Shanahan used a late pick on Cousins. Allen, long since out of town, found out and was furious. He knew that Shanahan was saying—to the rest of the league, in code—that Allen had botched the Griffin trade.

Allen had, in fact, botched the Griffin trade, which turned out to be the worst R*dsk*ns transaction since the 1968 day when the team sent a first-round draft choice for Gary Beban, then put him on waivers without Beban ever starting a game. Having Cousins around setting set passing records at Washington reminded everyone how badly Allen screwed up. Now Cousins is gone. Whew—what a relief!

Just to prove it was no fluke, Allen also paid Cousins about $50 million without ever making a bona-fide attempt to sign him to a long-term deal, thus achieving the worst of both worlds: big salary cap expenditures without stability at quarterback.

Bruce Allen so badly wanted to get Cousins out of town that the Potomac Drainage Basin Indigenous Persons ended up paying $71 million in guarantees and a young star, cornerback Kendall Fuller, to acquire Alex Smith and rationalize letting Cousins walk. (Washington also surrendered a third-round draft pick for Smith but is likely to get a third-round pick back in the NFL’s fog-shrouded free agent compensation process.) As the season gins up, expect from the sports media inscrutable leaks—perhaps using ESPN’s notorious “sources say” formulation—disparaging Cousins and praising Smith. Allen and his cronies will try to plant such reports hoping to make the Persons’ quarterback decisions look less clumsy, winning Allen an extra year of highly paid bumbling.

Smith is a good quarterback early and a letdown late. With the Chiefs, he was a consistent winner in the regular season but 1-4 in the playoffs, despite home playoff dates. This won’t matter in our nation’s capital because in eight years of Allen calling the shots, the R*dsk*ns haven’t won a playoff game anyway.

Recently the R*dsk*ns have been unable to stop the run, finishing last in rushing yards allowed in 2017. The team responded by investing consecutive number-one draft choices in defensive linemen from Alabama, Jonathan Allen and Da’Ron Payne.

Scouts and personnel directors feel safe in picking from the Crimson Tide roster because the Southeastern Conference has become a Triple-A league for the NFL. But the Tide is such a stacked team, players may make each other seem better than they really are. Several highly drafted Alabama athletes of recent years have been disappointments as pros, including Dee Milliner, Chance Warmack, Rueben Foster, Reggie Ragland, Cyrus Kouandjio, and of course Trent Richardson.

The Persons employed their second-round choice on running back Derrius Guice, who’s already out injured for 2018. As TMQ annually notes at draft time, head coaches and general managers flatter themselves by asserting the guys they drafted should have gone higher, since if this is so, then the people doing the picking are smarter than everyone else. Washington coach Jay Gruden took this to an all-time high by saying of Guice during summer camp, “We thought he might be the first player picked in the draft.” If the guy who was actually chosen 59th might have been chosen first overall, then Washington’s brain-trust must be way smarter than everyone else.

As for Chainsaw Dan, he purchased a team that was the epitome of sports success—titles, locally loved, financed its own stadium, years-long waiting list for season tickets—and has brought nothing but negativity. In 19 seasons under Chainsaw Dan, the team has posted two playoff wins. In the 19 previous seasons, Washington posted 16 playoff wins and three Super Bowl crowns.

On the upside, since the election of Donald Trump, Snyder is no longer the worst chief executive in the Washington, D.C. area. And the season-tickets backlog problem is taken care of. Once fans waited years for a chance at a R*dsk*ns season ticket. Now there is walkup admission on gameday, though the team has reduced stadium capacity by covering thousands of seats.

Next Week. Why the 2018 season will be the last great season of professional football. Plus Tuesday Morning Quarterback’s Super Bowl pick, bearing in mind this column’s motto: All Predictions Wrong or Your Money Back.