If the European Union were simply a club of nations, a forum through which neighboring states could arbitrate their disputes, no one would have a problem with it. And Britain wouldn’t be holding a referendum on June 23 on whether to leave.

What makes the EU different from every international association is that it legislates for its member states. Its foundational treaty, the Treaty of Rome, doesn’t simply bind its signatories as states; it creates a new legal order, with precedence over the national laws of the member nations, directly binding upon individuals.

When you join the EU, you don’t simply agree to do certain things. You subordinate your courts to the European Commission and the European Court of Justice. These bodies habitually make new laws that go way beyond anything you signed up to when you joined. And, under the doctrine of “direct effect,” those new laws have automatic force within your country, not requiring parliamentary implementation.

Americans have traditionally been touchy about national sovereignty, and with reason. The Founding Fathers understood that sovereignty is the basis of accountable government. To this day, the United States is arguably the most reluctant nation on Earth to sign international treaties and conventions.

But I wonder whether the Americans opposed to, say, the United Nations or the International Criminal Court have any idea how lucky they are to have the luxury of worrying about those bodies rather than the EU.

Let me give you an example of what real loss of sovereignty looks like. The EU treaties provide for freedom of movement within the 28 member states, a right that has been creatively interpreted over the years to mean reciprocal social security entitlements, voting rights and much else.

Seeking a better deal from Brussels prior to the referendum, Prime Minister David Cameron asked for a cap on the number of EU nationals entering the U.K., but was told that such a cap would be illegal.

Suppose for the sake of argument that he had tried to go ahead anyway, and had passed an Act of Parliament limiting net inward migration from the rest of the EU to 100,000 people a year.

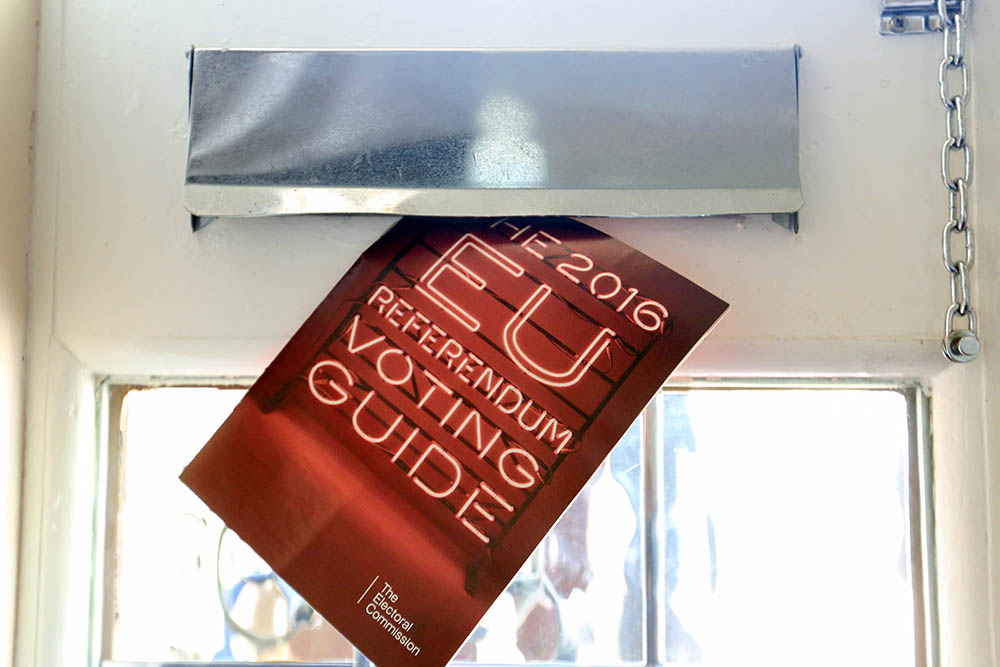

Britain is holding a referendum on June 23 on whether to leave the European Union. (Bloomberg Photo)

The EU wouldn’t need to take Britain to court for breach of treaty; the 100,001st entrant would simply demand residence rights directly from the British courts; and they, obedient to the doctrine that gives EU rulings precedence over national statues, would uphold the claim.

OK, you might say, so how is that different from Pennsylvania accepting the jurisdiction of federal institutions? It’s not. The honest case for the EU is precisely that it will eventually become a federation, like the United States of America. Continental leaders are open about this.

“I work, dream and live for the United States of Europe,” said Italy’s leader, Matteo Renzi. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has explained how it will work: The European Parliament will become the USE’s chief legislature, like the U.S. House of Representatives, while the Council of Ministers, which represents the 28 national governments, will become an Upper House, like the Senate.

In Britain, unlike on the Continent, no mainstream politician admits to being a Euro-federalist. British members of Parliament know that precious few of their voters feel European. Britain’s closest links — links of language and law, habit and history, custom and kinship — are to the other Anglosphere democracies. The idea that we are part of a cultural continuum that includes Austria but not Australia is ridiculous.

When Pennyslvania agreed to confederate, and later federate, with the other 12 states, it did so as part of a pre-existing nation. James Madison noted at the time that the 13 colonies had long been bound by language and law and “similitude of religion.” The same is not true of Europe, where attempts are being made to forge a single state out of very different nations.

A better parallel would be if the U.S. accepted the superior jurisdiction of the Organization of American States; if it recognized a Pan-American Parliament in, say, Managua, which had the power to overrule acts of Congress; and if it accepted the Pan-American Peso, administered by a Central Bank in, let’s say, Brasilia, as its currency.

Cameron originally promised a referendum under pressure from Euroskeptics within his own party and the U.K. Independence Party; but the campaign is cutting across party lines.

It’s true that the sovereignty argument is generally more appealing to Conservatives, and the two most prominent Leave campaigners are Tory MPs Boris Johnson, the former Mayor of London, and Michael Gove, the lord chancellor (i.e. the man who oversees the judicial system).

Yet there is also a palpable class divide. Many traditional Labor voters are sick of a system that seems to be designed by and for lobbyists and corporate affairs types. I see the split every day on the campaign trail.

U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron originally promised a referendum under pressure from Euroskeptics within his own party and the U.K. Independence Party; but the campaign is cutting across party lines. (Bloomberg Photo)

The strongest support for Vote Leave is among low-income voters. Speaking to a conference of CEOs from multi-nationals recently, I wondered whether I would have any friends in the room at all. In the event, the waitresses, receptionists and cameraman all made a point of assuring me of their support.

The Remain side seems almost to have gone out of its way to emphasize its elitist credentials. It campaigns chiefly through the medium of letters to the London Times signed by grandees: professors one week, captains of industry the next, environmentalist pressure groups the next.

Understandably, seeing a coalition of politicians, civil servants and assorted dignitaries, many voters suspect a plot against the common man. And they’ve got a point. Almost all the organizations represented in these letters — the universities, the lobby groups, the big businesses — get grants of one kind or another from Brussels.

Concerns over sovereignty, in other words, are supplemented by a sense that the EU has become a racket, a way of redistributing wealth from the little guy to the people (including, for now, this author) lucky enough to be inside the system.

Who will win? As I write, the opinion polls are finely balanced, and it seems likely to come down to turnout on the day. The Remain side is confident that it has the advantage here, because rich and well-educated voters are traditionally likelier to cast their ballots. But I’m not sure that’s true this time.

There is, as both sides privately admit, an asymmetry of enthusiasm. Leave is organizing big rallies; Remain is organizing genteel seminars. Leave is campaigning on the streets; Remain is campaigning with targeted mailshots. Leave has thousands of volunteers stuffing leaflets through letterboxes; Remain, financed by Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan and the rest, purchases demographic data.

Leavers know exactly why they are voting: They want to take back control of their taxes, their laws, their borders, their democracy. Remain’s argument, by contrast, is essentially negative: Whatever is wrong with the EU, it contends, the alternative may be worse.

As the letters from the grandees failed to shift opinion, Remainers have begun to sound increasingly shrill. Leaving will endanger peace, Cameron says. It will please Russian President Vladimir Putin and delight the Islamic State. It will cause a recession, says the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

It will mean that Britain is never allowed to host the Olympics, says the Labor Remain campaign. It will trigger an ecological calamity, says the last Labor leader, Ed Miliband.

Now it’s possible that these scare-stories might have some kind of cumulative effect. Although people might laugh at each claim individually, the relentless scare-mongering might nonetheless create a mood of uncertainty. “They’re probably talking tosh,” the swing voter might say, “but why take the risk?”

Risk-aversion is deep in the human genome. It largely explains why 80 percent of British referendums have favored the status quo, a figure in line with other advanced democracies. As a Remain friend, who’s also a Conservative MP, put it to me: “It’s like banks. Everyone moans about their bank, but hardly anyone can be bothered to move their account.”

Maybe. Then again, if you thought the bank might fail, you’d move pretty sharpish. When Britain joined what is now the EU, back in 1973, it looked like the future. Western Europe had experienced extraordinary economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s, while Britain, which spent 30 years inflating away its World War II debt, had fallen further and further behind.

The Remain side seems almost to have gone out of its way to emphasize its elitist credentials. (Bloomberg Photo)

Today, the picture is reversed. Continental countries are struggling with twin migration and monetary crises, unlike the U.K., which had the good sense not to join either the passport-free area or the euro. Over the past five years, incredibly, Britain has created more jobs than the other 27 EU states put together. Many voters have concluded that reorienting away from the enervated eurozone is the safer choice.

The EU is showing its age. It’s a leftover from the top-down, dirigiste, big-bloc 1950s. But the rest of the world is going in the opposite direction. In an era of Skype and cheap air travel, regional customs unions look obsolete. The idea that we should meekly acquiesce in the rulings of transnational bureaucracies seems terribly 20th century.

What will happen if Britain votes to leave on June 23? Initially, not very much. Referendums are advisory in the U.K. and, although it is politically unthinkable that the government would defy the result, there would be no rush. My best guess as to when the separation would legally take effect is July 1, 2019, to coincide with the election of a new European Parliament and the appointment of a new European Commission.

Whenever it falls, the day Britain formally withdraws will look just like the day before.

All the technical standards that the U.K. has had to adopt over 45 years will remain in place unless and until they are disapplied; the trade arrangements will remain unchanged until one side or the other changes them; the reciprocal deals on healthcare and the like will be left in place unless either Britain or the remaining EU decide to abrogate them.

Brexit, in other words, is a process, not an event. Lord Rose, the former boss of the famous retailer Marks and Spencer who chairs the Remain campaign, inadvertently gave the game away when he said: “It’s not going to be a step change, it’s going to be a gentle process.”

He went on, before his horrified spin-doctors could shut him up: “Nothing is going to happen if we come out of Europe in the first five years, probably. There will be absolutely no change. Then, if you look back 10 years later, there will have been some change, and if you look back 15 years later, there will have been some.”

Quite. Still, it’ll be worth it. Apart from recovering our freedom, we’ll have shown that we’re prepared to disregard the hectoring of international bureaucracies, megabanks and every foreign leader from whom Cameron could call in a favor — including President Obama, who inadvertently boosted the Leave campaign with what was seen as a ham-fisted intervention last month.

Take another look at your Declaration of Independence. See how aptly the colonists’ grievances might now be leveled against the EU: “a jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution”; “abolishing the free system of English laws”; “declaring themselves invested with the power to legislate for us”; “obstructing the Laws for the naturalization of foreigners.”

Leave campaigners, appropriately, are calling June 23 “Independence Day.” Americans, of all people, should sympathize.