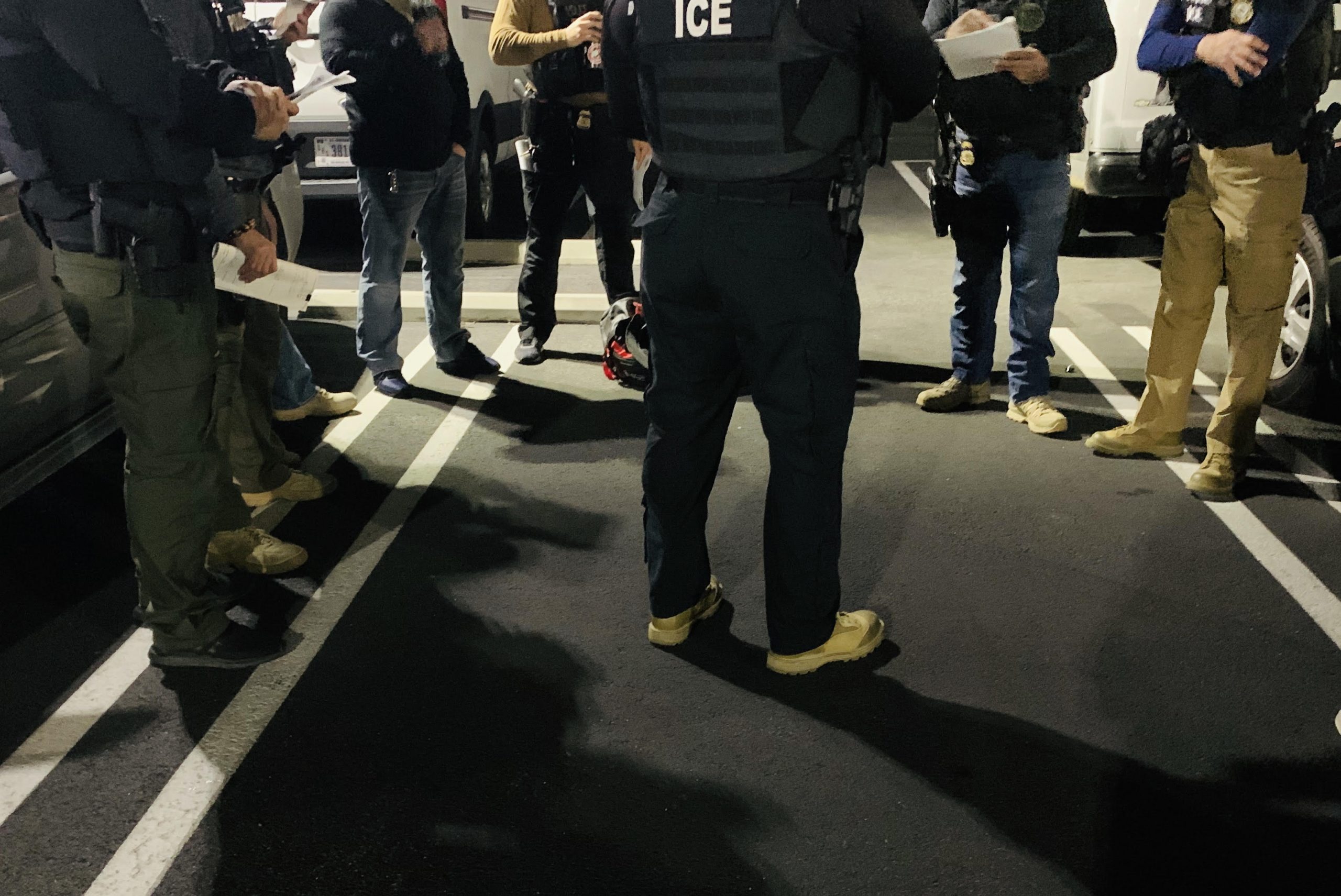

ORANGE COUNTY, California — It is 4:32 a.m., and downtown Santa Ana is quiet but for a dimly lit parking lot where 10 federal immigration officers are strapping on bulletproof vests before embarking on today’s operation.

A five-minute huddle kicks off what will be a more than five-and-a-half-hour mission by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers to arrest six people who are residing here, about 30 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles. The six are illegally in the country and appeared on ICE’s radar when they were arrested by local law enforcement. Otherwise, they likely would have gone unnoticed and not become a priority for removal.

David Marin oversees the nearly 600 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations officers in the region. He says today’s operation may look like raids to bystanders, but his officers will not be running into every house on a block or arresting groups of random people — they are looking for specific individuals. Their approach is more surgical and less aggressive.

“It’s not Live PD. It’s not Cops. We’re not going to be running around and chasing people,” Marin says during our two-mile drive from the parking lot to the first spot they will stake out this morning. He’s wearing an earpiece and constantly surveying our immediate area. Most of the arrests the Santa Ana-based officers will attempt today are planned for when the people leave their homes in the morning. They do it then to avoid going inside, where children or weapons may be present.

Due to the state’s various “sanctuary” policies, local law enforcement usually cannot turn someone over to ICE, or even notify the agency, when someone in custody makes bail or is released. But most of the seven counties in this region help ICE to the legal extent they can.

Los Angeles County is the only one that has cut all cords, and because the Los Angeles County Jail is the largest jail system in the country, its approach has massively curtailed the number of people it can easily transfer into custody, Marin explains. In fiscal 2019, ICE asked that 11,000 people who were booked into the jail be turned over. Approximately 500, or 5%, were turned over because they committed one of dozens of serious crimes, such as murder or rape, that are among the exceptions to the sanctuary law barring local police from turning over detainees.

Los Angeles Sheriff Alex Villanueva pushed ICE out last June, shuttering its round-the-clock presence at the jail. The 1,400 people whom ICE would normally have taken into federal custody each month were suddenly out of immediate reach, and resources had to be used to find them. With 19.5 million people living in Marin’s area of responsibility, approximately 1 million of whom are illegally present, he says, he has to prioritize which ones his staff will pursue. Other federal entities go after illegal immigrants with terrorism ties, leaving ICE all the others.

“For us, it’s criminals: those who have been arrested by local law enforcement, those who have a final order of removal, those who have been through the system —they’ve been ordered removed but never left,” Marin says. “In addition, it’s those that have been deported and they’ve returned — that’s another huge population that we have here in Southern California.” The standards on who is targeted was set in the Bush administration, changed halfway through the Obama years to focus on the worst offenders, and changed back to the Bush standard under President Trump.

These daily operations, unfolding simultaneously across major U.S. cities, are what grow the year-end count of interior arrests to tens of thousands. Each day, hundreds are arrested in predawn operations such as the one about to unfold in Santa Ana. This morning alone, 70 officers in the region are out. The people they are pursuing have taken from weeks to more than a year to pursue, depending on officer caseloads and available information on the person.

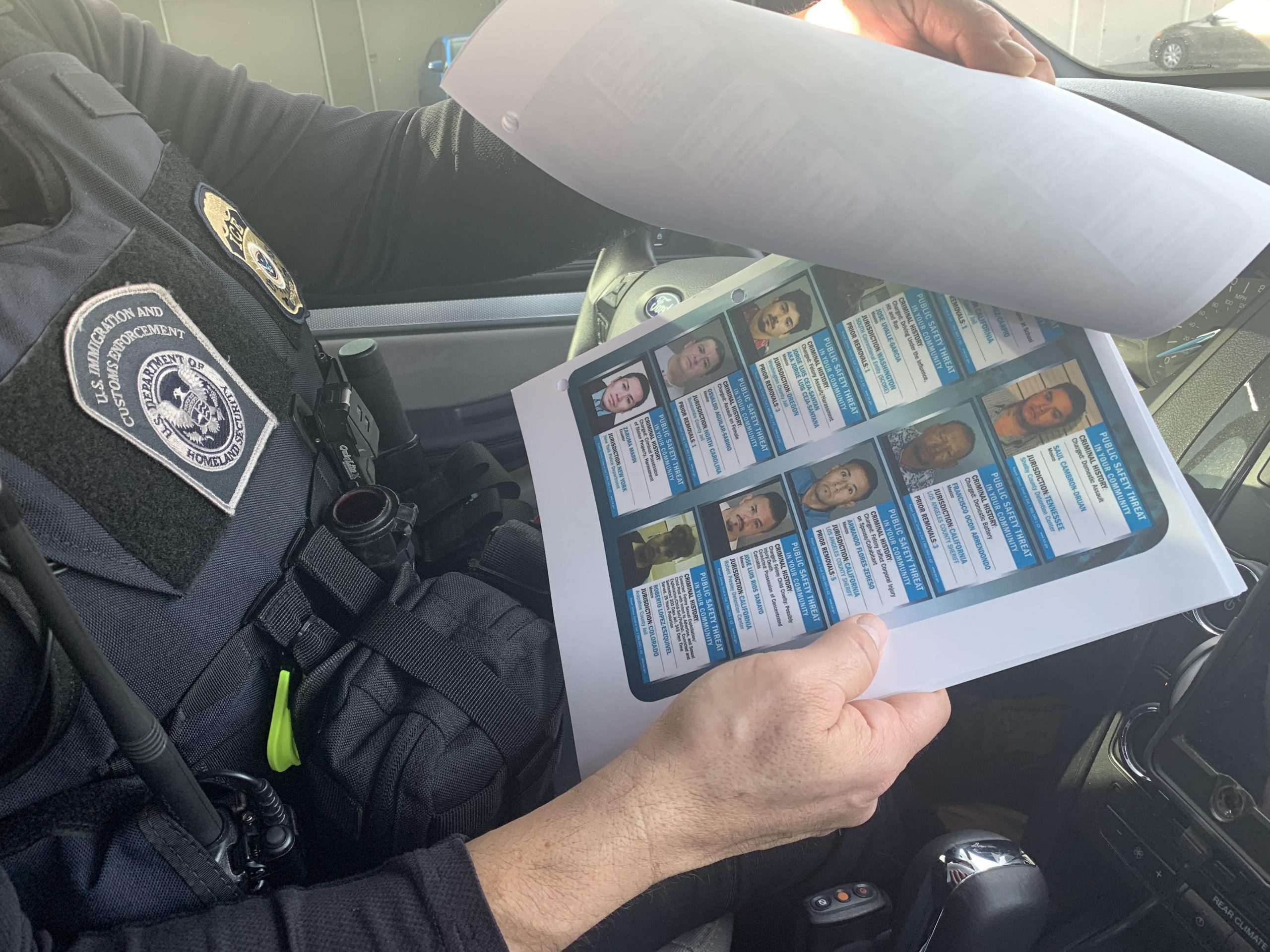

All six men who officers hope to find today have been convicted at least one time for driving under the influence, or DUI. Marin recently directed his hundreds of officers to focus on finding DUI offenders, as well as those who have committed crimes against children or domestic partners.

Two of the six people whom officers are seeking today were Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals beneficiaries, a program that was created during the Obama administration for immigrants who were illegally brought into the country as children. DACA recipients are protected from deportation as long as they keep a clean criminal record.

We pull up around 5 a.m. near the spot a 40-year-old Mexican man who has two DUI convictions is expected to appear. He was originally arrested for illegally crossing the southern border in 1999, returned to Mexico, then attempted it again, this time with success. He has been arrested half a dozen times since then, on top of the two DUI convictions he received. ICE asked to take him into custody at the jail twice but says the requests were ignored. Marin says it has taken 10 months since he was last released to go after him, due to resource constraints.

ICE has been surveilling this man for days to determine the safest way to take him into custody. Schools, hospitals, and churches are out of bounds. Marin says the man’s wife normally drops him off at his car, usually parked at the same spot on a specific street corner. Officers want to nab him here because they do not need a warrant to make an arrest on public property, unlike at his home, where people can refuse to leave. But these types of arrests are risky because the person could use the vehicle to run over officers, lock himself inside, or use a weapon inside the vehicle against officers.

We are sitting a block down from the corner. Other officers are posted in unmarked cars around the same area. The normal drop-off time comes and goes with no sign of the man. Marin says this is not unusual, even after lots of planning. They will try to find him another day. It’s almost 6:30 a.m.

We move on to a nearby home, where six officers hope to find the second target, a 22-year-old who was also a DACA recipient and has been convicted three times of DUI and released by local law enforcement, despite ICE asking for notification beforehand. Instead of waiting for this man on the street, officers hope to find him at his home. They silently walk up the incline driveway and surround the home and two-story residential building behind it. One officer takes the back. Marin flashes his flashlight into a side window, an officer bangs on the front door, while another stands on the front lawn with his back to the house as he watches the street.

After several minutes of knocking, the officer at the front door comes down from the stoop to report that a resident said the person they are looking for lives in a different house next to this property. The group runs to the back looking for the street number they were just given and then spot the new home. Officers knock on the door and look around the property. Two people come out of the side door and speak with officers through a 7-foot-tall fence that blocks anyone from getting inside. The resident said the man they are looking for does not live here any longer and returned to Mexico six months ago.

It’s another unsuccessful bust for Marin’s team. The larger group breaks up again to go after two more people at separate locales. It’s almost 6:45 am, and one person is In custody from an arrest that others in the group made while we were at the first house. We head to the third location — it will be another stakeout for a man they say walks to his car from a nearby home at a certain time.

Marin says they are looking for a 28-year-old Mexican man who illegally crossed the southern border in 2018, was caught by Border Patrol, and returned to Mexico that day — then was caught again illegally crossing and returned again to Mexico. At some point between then and last month, he finally made it past Border Patrol and into the country. ICE knows that because he was arrested on Dec. 16, 2019, for DUI and having an open container of alcohol. ICE officers in multiple cars sit near his car for more than two hours with no sighting. The wait is occasionally interrupted by passersby who stop to take pictures of Marin’s vehicle and tags, which he says they will share online to alert people that ICE is in the area.

Other officers in Santa Ana arrested a second person who has been taken to the agency’s in-town booking center. He will either be transferred to the Adelanto Detention Center north of Los Angeles or, if the person is from Mexico and has previously been removed, returned south of the border that afternoon.

Officers will call it quits late morning with just two of the six people they wanted to find in custody. Marin shrugs it off. He says taking someone off the street before they can commit another DUI, one that could kill a citizen or noncitizen next time, is at least something.