This isn’t how Chuck Schumer imagined he’d end up as majority leader, but he’ll take it.

The New York Democrat, like most political pros, saw a path to the Senate majority through 2020 wins in Maine, North Carolina, and other competitive races. But their nominees flopped, with Maine’s Sara Gideon proving no match for veteran GOP Sen. Susan Collins and the candidacy of North Carolina Democratic nominee Cal Cunningham’s imploding in a sex scandal.

Schumer, though, finally won his long-sought prize in a pair of Jan. 5 runoffs in Georgia. Democratic candidates Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock each beat Republican senators in a long-red state where, nonetheless, President-elect Joe Biden defeated President Trump two months earlier.

Schumer will ascend to majority leader once Biden becomes president on Wednesday at 12 p.m. and Ossoff and Warnock are sworn-in to the Senate, which under Georgia ballot certification law must happen by Friday. Incoming Vice President Kamala Harris will be the tiebreaking vote in a Senate divided 50-50, ending the Republican majority that has held for more than six years. (Harris, a California senator for four years, is set to be replaced by Alex Padilla, California’s secretary of state.)

And with a Democratic president and a Democratic majority House, albeit narrowly, the party will have full control of elected government for the first time since President Barack Obama’s first two years in office.

Senate majority leader will be the latest political achievement for Schumer, the whip-smart, phone number-memorizing, cereal-loving Brooklyn native. Schumer has a tough task in taking the reins of the Senate amid Biden’s new administration, pushing confirmations and policy priorities through a 50-50 divided Senate.

That will require the 70-year-old New York Democrat to gain support from Republicans to meet the 60-vote threshold due to the filibuster, assuming it stays intact. And in his own caucus, ideological divisions span from Democratic socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont to centrist West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, setting the stage for intraparty battles.

Schumer has 46 years of career politician preparation for the job.

A Brooklyn-raised son of an exterminator and a homemaker, and the oldest of three children, Schumer graduated valedictorian from the public James Madison High School, also the alma mater of Sanders and the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. His first job was as an assistant for test-prep empire founder Stanley Kaplan, who said in his autobiography that Schumer scored “close to a perfect 1600” on the SAT. He still sometimes sprinkles his public comments with SAT vocabulary words.

“He is really the smartest one in the room,” said Jason Abel, now a partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP, who worked for Schumer as counsel from 2007 to 2011. “When you meet and discuss with him, you have to be prepared as a staffer.”

“I don’t know if he has a photographic memory, but he’s got a crazy good memory,” said Christopher Hahn, who was an aide in Schumer’s office from 2000 to 2005 and is now a Democratic pundit and radio host.

Schumer’s academic successes got him into Harvard, where he first started by focusing on science courses with his sights set on a chemistry degree. But a stint volunteering on Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s ill-fated 1968 Democratic presidential campaign, which helped force President Lyndon Johnson to end his own reelection bid, sparked an interest in politics.

“I said to myself, ‘Wow. A ragtag group of students and other assorted nobodies toppled the most powerful man in the world. This is what I want to dedicate my life to,’” Schumer recalled to the Harvard Crimson in 2018.

He became president of Harvard’s Young Democrats club, interned on Capitol Hill for New York Democratic Rep. Bert Podell, and wrote his senior thesis on congressional politics and time allocation.

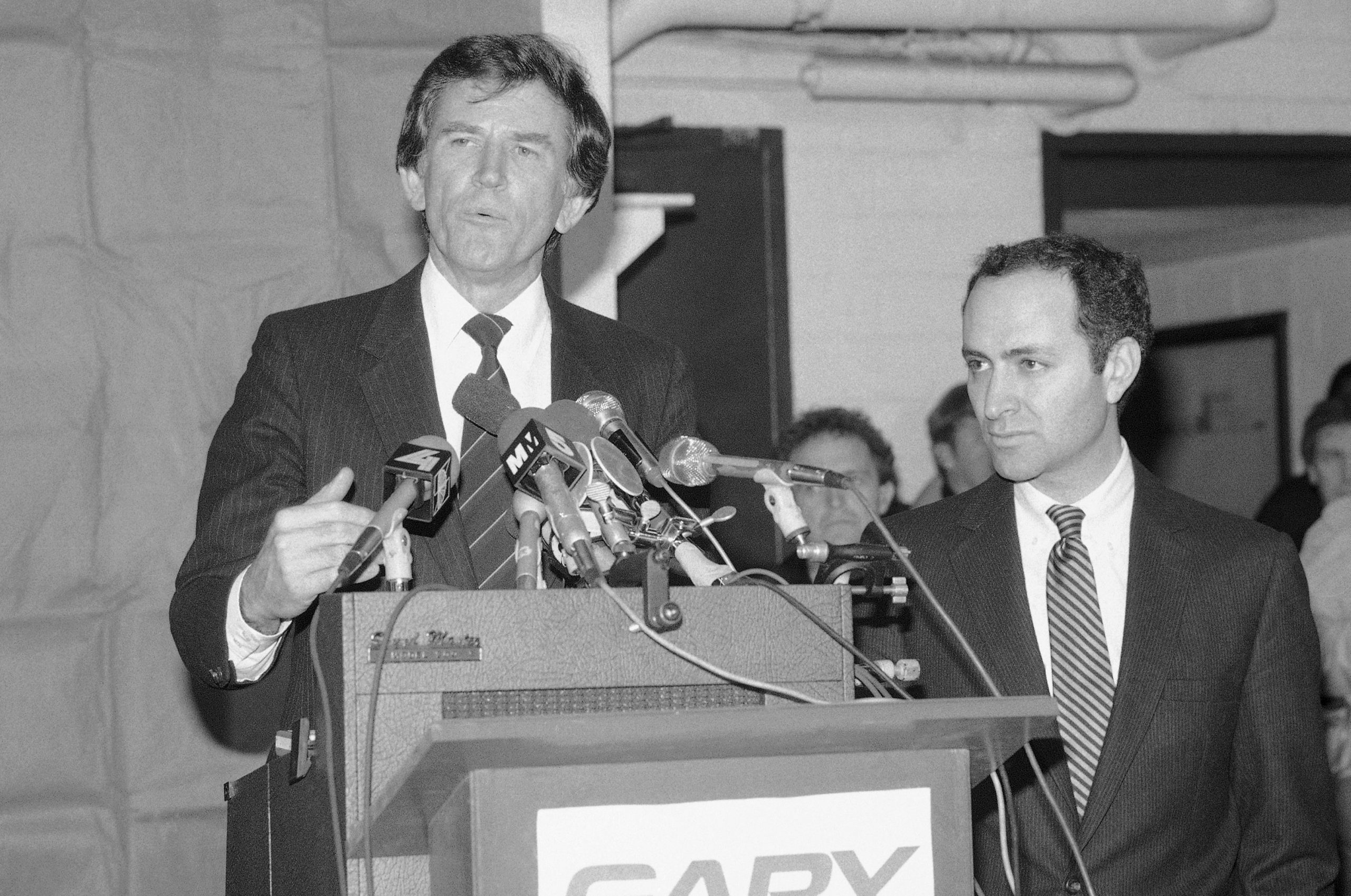

Schumer went on to earn a J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1974 and passed the New York bar. But he never practiced law and instead was elected to the New York State Assembly at 24 years old in 1974. Schumer won an open House seat in 1980 — the same year he married Iris Weinshall, now the chief operating officer of the New York Public Library and a key member of Schumer’s inner circle. They have two children together.

Jim Kessler, who worked for Schumer from 1993 to 2000, including as a legislative director, said that by then, Schumer was a “well-known and an immensely talented politician” who was “pretty well-respected and definitely aggressive legislatively.”

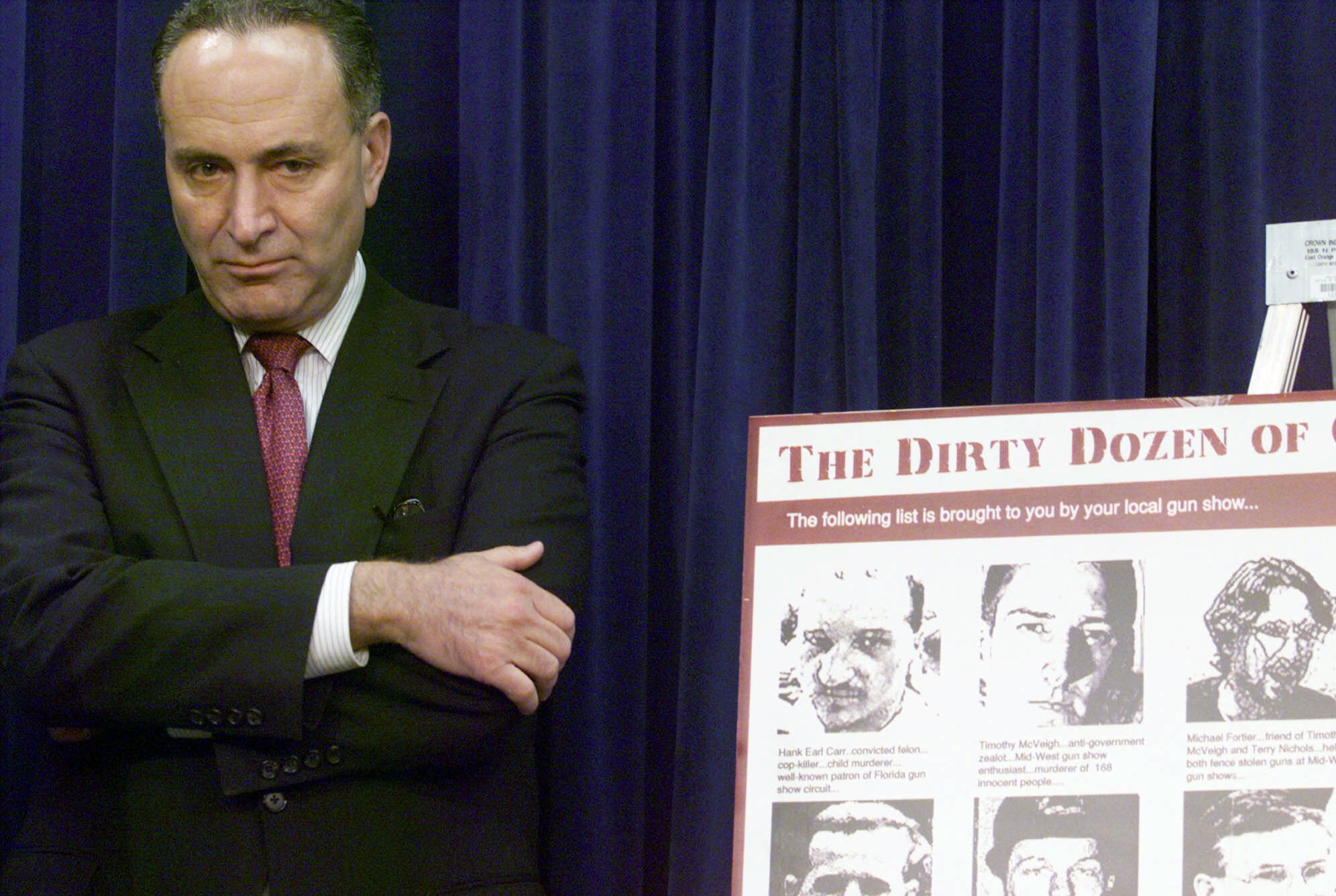

Schumer wrote the Brady Bill, which mandated background checks on gun sales and was signed by President Bill Clinton in 1993; was a lead sponsor of the 1994 crime bill; and also helped write the Violence Against Women Act, which Biden also frequently cites as one of his own achievements. He developed a reputation for mastering the media game — or, as some less charitable would say, having a taste for being in the limelight.

Schumer was “very strong on Democratic messaging,” said Kessler, a co-founder and vice president of the center-left think tank Third Way.

“He was light years ahead of others colleagues,” Kessler said. “But it wasn’t really recognized in the House caucus so much.”

At the time, some members of Congress who had been in office for 10 or 12 years “had virtually no contact with the speaker of the House,” Kessler said. On some issues that were an uphill battle within the Democratic Caucus, such as gun control legislation, Schumer would assemble his own whip team to get the votes needed to pass his legislation.

After Republican Newt Gingrich became speaker in 1995, Schumer took more of a lead on Democratic messaging. He analyzed what Gingrich’s “Contract with America” would mean for New York City families and helped replicate that for other members of the House.

But still, while Schumer was liked by many of his colleagues, he was a bit of an outsider. “They weren’t looking at him to take a leadership role there,” Kessler said.

It wasn’t until he joined the Senate that he eventually caught the notice of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, who put Schumer on the path to eventually becoming leader of the Senate caucus.

Schumer was elected to the Senate in 1998, defeating three-term Republican incumbent Sen. Al D’Amato, itself a noteworthy achievement that drew notice from Democratic colleagues. Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy took a liking to him. When fellow New York Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan retired after 2000, Schumer became the senior senator from the state during his first term.

“It’s one of the political and financial and news centers of the United States market, if not the world. So, being the senior senator from the state of New York is a big deal,” Hahn said.

But he was still low in the ranks of the Senate and considered running for governor of New York in the 2006 cycle.

Reid helped convince him otherwise. He put Schumer in charge of the Democrat Senatorial Campaign Committee, charged with recruiting Senate candidates and helping them get elected. His successes in the post created the foundation that helped Democrats briefly hold a 60-vote supermajority in 2009, during which time the Senate passed major legislation such as the Affordable Care Act.

“It just seemed that he was always in the center of everything. And we were getting a lot of accomplished, even in his first term. Usually, you know, a first-term senator, it’s difficult to get things done. But that did not stop Chuck Schumer,” Hahn said. “He was extremely hard charging.”

Former aide Abel said that Schumer attempted “to reach out to colleagues no matter how conservative they might be.”

“He was a legislator, and he likes to lead when it comes to legislation and work across the aisle,” Abel said.

Reid created a new leadership position for Schumer to fill starting in 2007, vice chairman of the Senate Democratic Caucus. And when Reid retired after 2016, it was Schumer, rather than No. 2 Senate Democrat Minority Whip Dick Durbin, who became leader of the caucus.

“I’m sure it was tough on both of them because they do like and respect each other quite a bit,” Kessler said.

Durbin threw his support behind Schumer before news of Reid’s plan to retire spread. But public posturing and feuding between the two men and their offices over whether or not Schumer had agreed to keep Durbin on as whip swept the headlines.

It was an end of the buddy-comedy persona crafted around the two men. Durbin and Schumer were for decades roommates in what was dubbed Capitol Hill’s “Animal House,” shared with then-California Democratic Rep. George Miller, who owned the house, and a rotating cast of other roommates. Schumer had one of the two (often unmade) beds in the living room and was accused by his roommates of hogging cereal (one of his favorite foods). Miller sold the house after retiring in 2015.

“He’s an eat-Chinese-food-out-of-a-card-carton-with-plastic-chopsticks guy,” Kessler said of Schumer. “If you wore a really expensive suit, he wouldn’t recognize it.”

The incoming majority leader is also famous for memorizing the phone numbers of every senator in his caucus and those of his aides — quite the change in leadership style from when he barely spoke to the speaker when he was in the House. Schumer held on to his flip phone for years, only giving it up in 2017.

At an event years ago, Kessler brought along his then-girlfriend, now his wife. “Remind me what her name is — I know her phone number,” Schumer said, Kessler recalled. While a lesser man might have been offended, Kessler said, he knew that Schumer would often call her when looking for him.

Schumer, his former aides say, is poised to manage the ideological divisions in the Democratic Party as well as anyone.

“When he became a Democratic leader, he almost immediately expanded his leadership team, and brought on not just Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren [of Massachusetts], but Joe Manchin and Mark Warner [of Virginia],” Abel said. Schumer helped recruit and coach Sanders (who attended the same high school as Schumer several years before him) and Warren in their first Senate runs.

“The way that the caucus stayed together through some very, very heated legislative battles over the last several years is proof of that style being effective,“ Abel said.

Schumer visits each of New York’s 62 counties every year, a tradition that not only keeps him in the good graces of voters but keeps him in tune with the widely varying Democratic Party, from dense New York City to the rural upstate, reflecting the United States as a whole.

Republicans are wary of Schumer and the coming trifecta of Democratic control of government, bracing for the possibility of massive changes such as increased gun control, student loan cancellation, climate policy regulations, tax increases, and steps toward “socialism.” The biggest fears include elimination of the filibuster, paving the way for expansion of the Supreme Court and eradicating its conservative majority, and cementing Democratic control of the Senate for years to come by making the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico states.

But a radical vision, former aides insist, is not the incoming majority leader’s style.

“There is nothing radical about Chuck Schumer,” Hahn said. “Chuck will work with them [Republicans] when he can. When there is a brick wall of opposition, he will do what he has to do to make sure that the world’s a better place” for middle-class families.

Kessler recalled a Schumer-ism that he expects will guide the new majority leader through legislative battles: “Bipartisan when we can but alone if we must.”