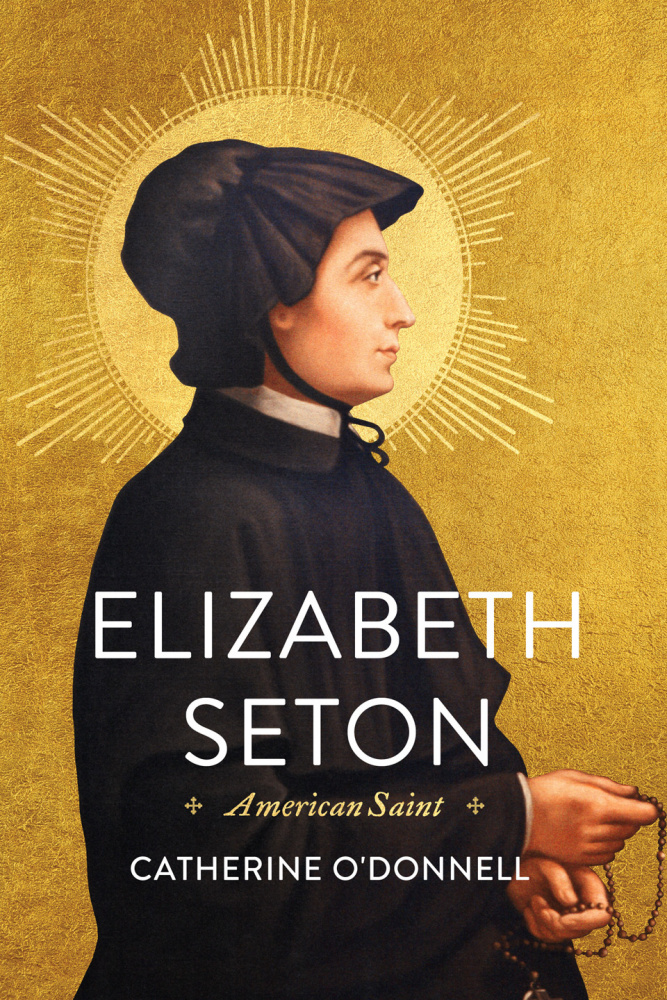

Elizabeth Seton

American Saint

by Catherine O’Donnell

Cornell, 508 pp., $36.95

In a damp, cold quarantine station in Italy, a woman nurses her dying husband. The year is 1803, and the woman, 29-year-old Elizabeth Ann Seton, struggles to pray. “My eyes smart so much with crying, wind and fatigue that I must close them and lift up my heart,” she writes in her journal. The family’s voyage from their home in New York, meant to relieve William Seton’s tuberculosis, has only brought him to death’s door. As their young daughter looks on, Elizabeth spends “the night listening for her husband’s breath and ‘kiss[ing] his poor face to feel if it [is] cold.’” Finally, William, after whispering “May Christ Jesus have mercy and receive me,” draws his last breath. Nine years after she married the man she called her “beloved treasure,” Elizabeth faces financial ruin, the rearing of five fatherless children—and religious uncertainty.

This is not the only tragedy that Elizabeth Seton would endure. Hers was a time of war, economic crisis, and ravaging disease, and each of these would touch her life. Yet she would found the Sisters of Charity. She would create a forerunner of the parochial school system. And she would become the first American-born Catholic saint.

Biographer Catherine O’Donnell asserts that Seton has been overlooked. “During the decades in which historians have explored the lives of women and the centrality of religion to early American life, Elizabeth Seton has rarely figured in histories of her era, and she has not been the subject of a new scholarly biography,” O’Donnell writes. “Yet by founding a successful religious community, she created spiritual and practical possibilities for generations of American girls and women.”

Born Elizabeth Ann Bayley in 1774, she was the second of two daughters of Episcopalian parents living in New York City. Her mother died when Elizabeth was 3 years old. Her father, a busy and renowned physician, quickly remarried, and his second wife so disliked having her stepdaughters around that she frequently shipped them to upstate New York to spend weeks at a time with relatives. It was while wandering through the upstate wilderness as a child that she first felt a connection to the divine—the earliest inkling of faith in what would be a lifetime of spiritual searching.

As an adolescent, she longed to escape the home in which she felt neglected: Her stepmother was hostile (and, O’Donnell speculates, abusing laudanum) and her father was aloof, often abroad, and likely carrying on an affair with another woman. One night, Elizabeth came close to suicide. Although she envied the tranquil life that her devout Protestant neighbors appeared to lead, she did not feel particularly attached to the Episcopal church and considered institutional religion too rigid. Instead, she felt drawn to philosophy and adopted a stoic attitude toward pain and suffering.

When Elizabeth fell in love with the wealthy merchant William Seton, marriage presented a welcome chance to get away from her turbulent life. As a well-off wife, she found herself drawn to supporting a benevolence society that served poor widows. “She felt compassion for New York’s destitute women,” O’Donnell writes, and found in that charitable organization “a way to turn her fears for her own family into useful action.”

The Setons bore five children of their own, but their house was also filled with young relatives. When Elizabeth was pregnant with her third child, six of William’s half-siblings also lived with them. Seton’s motherly duties left her little time for quiet contemplation. “I am so entirely occupied with [children],” she once complained in a letter, “that I have no time to indulge reflection.” O’Donnell adds, “If she sneaked away for a moment to think or read, ‘[she would] hear a half dozen voices calling Sister, or Mamma.’”

Still, she used every spare moment to hunt for peace and intellectual independence by reading and by taking notes in a commonplace book. She perused the Bible and Christian sermons, and pored over Rousseau (“dear J. Jacques,” she called him). With each new text, her perspective about life moved further from religious indifference to a hunger for divine truth. This intellectual interest was ignited into an intense devotion to her Christian faith after she met Episcopalian minister John Henry Hobart. Moved by his emotional sermons, she attended services as often as she could; after one in particular, she felt she had experienced a “Birth day of the Soul,” she wrote to a friend.

After William Seton died in Italy and, as Elizabeth awaited the ship that would bring her and her daughter home, she enjoyed the hospitality of the Filicchi family, longtime friends and devout Catholics. When she attended Mass with them, she found the liturgy, art, and piety of the worshippers so moving that she returned again and again. As O’Donnell puts it, the “woman who sailed for Italy with a ‘treasure’ of handwritten Episcopalian sermons [from Hobart] sailed for home a Catholic in all but name.”

Upon returning home, Seton shared with her pastor and family her desire to convert. They responded with surprise and scathing criticism; they saw Catholicism as heretical. For almost a year, she struggled over the decision. Still drawn to the Catholic Mass, she found herself wishing to believe what she still could not: “I cried in an agony to God,” she wrote, “to bless me if he was there [in the Eucharist], that my whole Soul desired only him.” Finally, she decided that she could no longer endure the Episcopalian liturgy; it now seemed to her a “pantomime.” She was received into the Catholic Church in March 1805.

With her newfound faith, Seton had a strong desire to devote her life to God. If she could have, she would have been a contemplative nun, and she dreamed of entering an Ursuline convent in Montreal. However, her children—the youngest was just 3 years old in 1805—still required her attention. She found another way to fulfill both dream and duty: by pouring herself into founding a new religious community, what would come to be called the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph.

Inspired by the Ursuline order and the French Daughters of Charity, in 1809 Seton and a handful of other women gathered in rural Emmitsburg, Maryland, to live a communal life of prayer and service through teaching. In conjunction with a group of priests, they established two boarding schools—one for boys, one for girls—which Seton’s own children attended. Next door, Seton lived with the Sisters of Charity and became “Mother Seton” to them. She gained a reputation for her religious fervor and tireless dedication to her work, and the community grew.

Seton would lose not only her husband but several friends and children to tuberculosis. But even after she herself caught the disease, she continued to work until the very end. “She donned the black flannel she’d set aside during the worst of her illness and resumed writing . . . the letters that had so long formed an important part of her voice as Mother,” O’Donnell writes. In 1821, surrounded by her Sisters and surviving daughter, she died at the age of 46.

Seton’s example touched countless others—those she knew personally and those later inspired by her. The priest who became her spiritual counselor, Simon Bruté, was “as eager that Elizabeth counsel him as he was willing to counsel,” according to O’Donnell. Protestant and Catholic leaders alike sought her advice. By the end of her life, Seton “had developed and shared her thinking [with the Sisters] in hundreds of pages of reflections, translations, and meditations, as well as in the words of Bruté’s sermons that she’d influenced or simply written.”

The task of running a religious community and a school weighed upon Seton, who still treasured her moments of solitude for reading and reflection. But through her determined work, writes O’Donnell, she created “a distinctive set of teachings about the nature and practice of charity, sacrifice, and love that would animate her spiritual daughters’ lives of benevolence for generations to come.”

Her commitment to guide the Sisters in their prayer and work helped the community thrive. Within the first two years, they had to change houses twice in order to accommodate the growing numbers. Their school for girls, St. Joseph’s Academy (which eventually united with its brother school, Mount St. Mary’s College), developed the reputation of a welcoming, affectionate place that forbade corporal punishment and attracted families from a variety of denominations.

But even when the schools and community enjoyed a positive reputation, things did not always run smoothly. Seton led the Sisters of Charity with such ardor that she frequently clashed with the priests appointed as her superiors; her religious vow of obedience was not always easy to keep. Of one priest, she wrote, “[He] remains now as uninformed in the essential points as if he had nothing to do with us.” Another priest collaborator likened her to a “gold brocade, rich and heavy indeed, but hard to handle.”

O’Donnell gives Seton the detailed portrait that she deserves—one that highlights her journey of faith, her contribution to Catholicism and education, and her “struggles over health and money, the dispossessions of war, the labors of motherhood.”

In the book’s epilogue, O’Donnell includes a passage from a remembrance written not long after her death:

On September 14, 1975, in a ceremony before some 150,000 people in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Paul VI declared Seton a saint. Today, her legacy includes not just the 4,000 members of the Sisters of Charity Federation but also the thousands of people who pray at churches named after her in over 40 states—as well as the countless schools that have erected statues honoring her dedication to children, education, and God.