Imagine being about the fiftieth-best employee in an organization of 400 people and making $24 million a year.

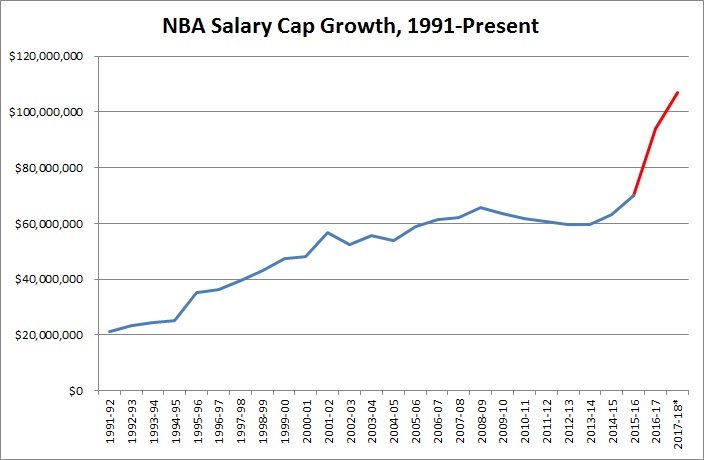

That’s the good life in the National Basketball Association, whose free agency period began Friday. Thanks to a nine-year, $24 billion television contract the league signed in 2014, salary caps for the NBA’s 30 teams will explode from $70 million to $94 million next year, with further growth well above $100 million expected in 2017 and beyond.

Such an economic boom is what enabled the Charlotte Hornets, a mid-market, decent club possibly on the rise, to offer Nicolas Batum, a solid, all-around player in his prime years, $120 million over a half-decade to remain in North Carolina. (Needless to say, Batum said yes.) Batum, 27, is known for his offensive versatility and ability to defend the wing, a coveted skill now that three-point shooting has become such an integral part of the professional game. The 6’8″ forward averaged a career-best 14.9 points per game last season, though not efficiently—he shot a subpar 42.6 percent from the field, and his three-point shooting wasn’t exact enough to offset it. Much of his value comes from the fact he’s a “box score filler”, in that he averaged six rebounds, six assists and a steal a night in the 2015-16 season. As NBA teams, paced by the nearly unconquerable Golden State Warriors, abandon traditional lineups with five distinct positions on the floor, players of Batum’s flexibility have added value.

But $24 million a year’s worth? There’s a good case the answer is yes. Measured in 2015 dollars, the NBA salary cap increased just 11 percent from 2001 to 2014. It increased by about that much from 2014 to 2015 alone. The $24 million jump next year represents a 34-percent year-over-year hike. In the 2017-18 season, speculation is that the cap will be between $107 million and $110 million. And so it goes as the NBA reaps the money from that TV deal.

Assuming Batum’s contract is structured reasonably with gradual inflation, his yearly cost won’t eat a percentage of Charlotte’s cap that prevents the team from pursuing other quality players or retaining young ones who are due for free agency. $24 million would represent 22.5 percent of the available money the Hornets have to spend on its roster in 2017-18—steep, but not past the amount most teams would be willing to spend on a core cog or legitimate top-three option. Batum was regarded between the fifty-fifth- and seventy-first-best player in the NBA heading into last season, and that was coming off a down year. He bounced back with several career bests in 2015. He’s the second-best player on a middling team and the third-best on a potentially good one, and can perform several functions for being just one guy.

Plus, like it is in any sport, teams don’t just have access to all players, priced perfectly, in a wide-open market. The depth of free agent classes varies by year. As it relates to this one, a player the caliber of Kevin Durant—the sublime, lanky Oklahoma City forward who plays like a guard—doesn’t come available often, and he has many suitors from which to choose. Teams often have to luck into a star via the draft to alter its fortunes, or be so adept with player development and coaching, a la the San Antonio Spurs, that they find ways to be competitive regardless of the quality of players in a given draft or free agent class.

Clubs like the Hornets are just trying to get better. They don’t have a top-10, franchise player who, complemented with the right people, can carry them deep into the playoffs. Short of that, they and teams like them are executing a roster management strategy—theirs includes obtaining versatile players—and attempting to improve with what’s available to them. Batum might be expensive for what he offers. But he’s arguably more expensive to let go.

The lesson to you professionals, as always: Make yourself indispensable to your organization. You, too, might end up earning $24 million a year someday.