The Medal of Honor is the nation’s highest award for battlefield valor, and every citation can be an emotional rollercoaster, even written in dry, bureaucratic language.

All recipients, living or dead, are proven heroes, but the list of people can be daunting to go through. As Americans reflect on the sacrifices of troops this Memorial Day weekend, here is a sampling of recipients from every major conflict from 1900 until now.

Army Spc. Ross McGinnis, Iraq war

AP Photo

McGinnis saved the lives of four fellow soldiers on patrol when his vehicle was attacked in Northeast Baghdad on Dec. 4, 2006.

While McGinnis was manning the .50-caliber machine gun on top of the vehicle, an insurgent threw a fragmentation grenade inside. McGinnis, age 19, yelled “grenade … it’s in the truck!” At this moment, he had the choice to either jump out of the vehicle or cover the grenade and prevent others from injury. Without hesitating, he jumped on the grenade. McGinnis’ platoon sergeant, Cedric Thomas, recounts how he saw McGinnis quickly “pin down” the grenade. Thomas said, “He had time to jump out of the truck … he chose not to.”

McGinnis, a private first class at the time, was posthumously promoted to specialist. Doing what he did was a matter of kindergarten math, McGinnis’ parents said. “The right choice sometimes requires honor.” He was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 6, 2008.

Army Staff Sgt. Robert Miller, Afghanistan war

Wikimedia Commons

In January 2008, Miller volunteered to lead a team of Afghan National Security Forces and coalition soldiers on a combat patrol along the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Their mission was to confirm enemy forces were in a specified compound and help get Air Force bombs on the target.

The coalition was moving toward the suspected building through a narrow valley. When they got close enough, there was a boulder that couldn’t be moved by ordinary means. Staff Sgt. Eric Martin recalled, “We had to come to a stop again and blow that boulder. I believe that’s when the enemy was tipped off.” As the coalition was maneuvering into position, they started taking enemy fire. According to Martin, there was nothing unusual about the fight, until bombs started dropping and the coalition fired heavy weapons at the compound.

Martin said Miller was always prepared for a fight and had packed heavy firepower that night. As the fight got within 50 feet, the coalition leader, Capt. Robert Cusick, was wounded immediately and Miller became the commander. “[Miller] bounded forward; we moved back,” Martin said. While Martin and his teammate tended to their wounded captain, Miller kept moving forward, throwing grenades and constantly shooting. Miller’s actions supressed the enemy until backup could arrive. “He saved lives that day…it was in his personality.” This was the last time his teammates saw Miller alive.

Miller’s teammates said it was his concern for the team that drove him. “It’s about doing the right thing and not letting our brothers down.” Miller was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor Oct. 6, 2010.

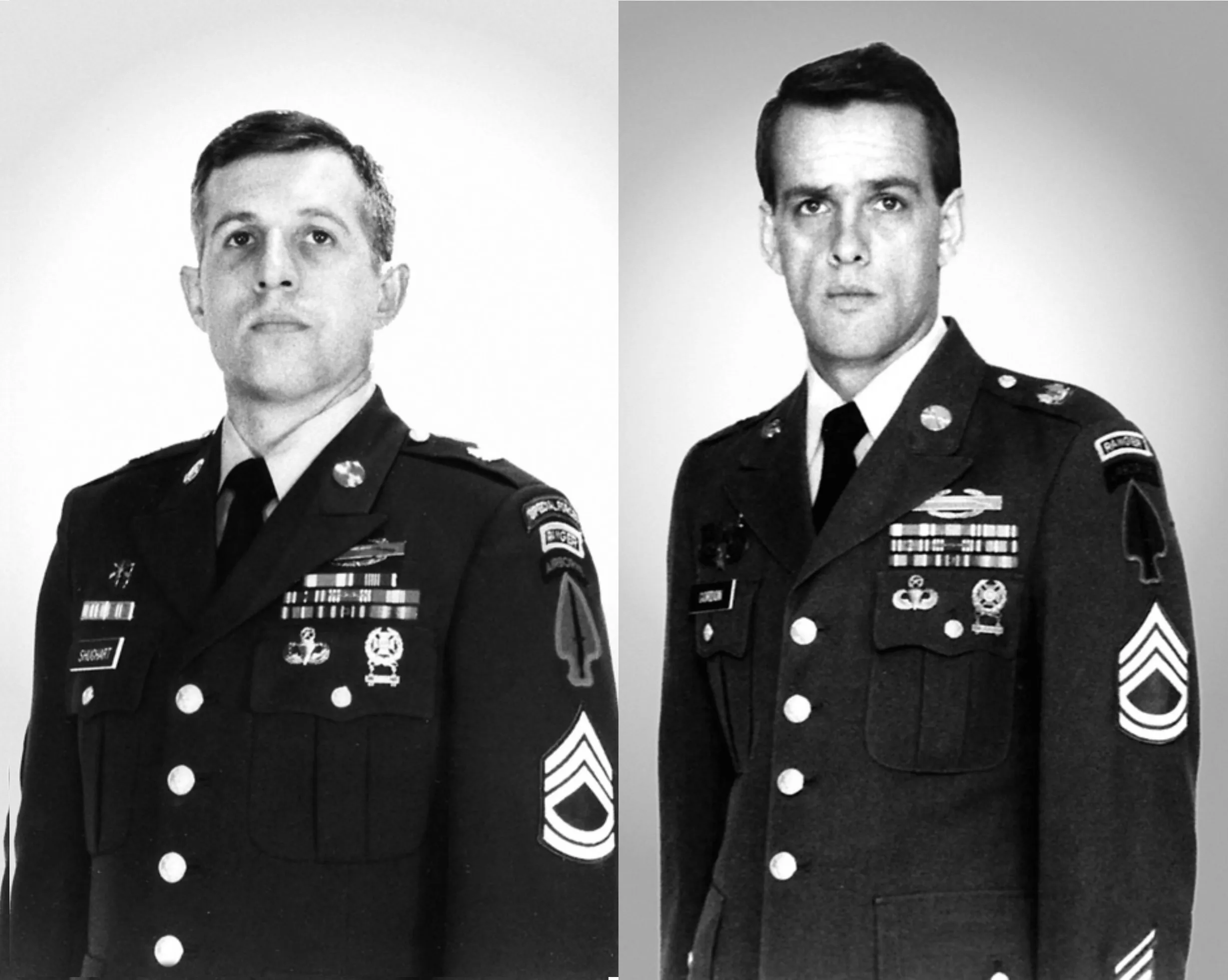

Army Master Sgt. Gary Gordon and Sgt. 1st Class Randall Shughart, Somalia

Wikimedia Commons

The streets of Somalia, Mogadishu, were filling with armed insurgents, American troops were pinned down, and a Black Hawk helicopter was just shot out of the sky. Yet Gordon and Shughart volunteered for what would be a suicide mission to rescue the doomed helicopter pilot.

Gordon and Shughart, Army Delta Force snipers, were circling over the Black Hawk crash site when they saw a growing mob of armed militia troops getting closer. After three frantic requests back to headquarters, their mission to rescue the helicopter pilot was approved. Gordon and Shughart knew there was no backup. There was no one who would be able to save them.

The plan was to maneuver Gordon and Shughart’s helicopter onto the crash site, but that was quickly scratched. A barrage of insurgent gunfire and rockets hit their own helicopter. Gordon and Shughart were forced to jump out 100 meters away from the downed Black Hawk while their helicopter pilot flew the injured bird back to base. Chief Warrant Officer 3 Michael Durant, the severely injured helicopter pilot, recounts his experience saying, “I never saw where they came from … it was a surreal feeling. I mean it was like this awful situation that you just realized you’re in is now suddenly over.”

As the militia mob encompassed them, Gordon and Shughart shot in every direction. It is unclear who died first, but Durant recalls a Delta operator “sounding almost irritated” when he was hit. The remaining operator had no option but to continue clearing the streets of the militia. He went to the downed helicopter, found extra ammunition, and took to the streets. For as long as he could, the remaining operator did everything possible to overcome the mob. Eventually, the opposition was too much and the remaining Delta operator was killed.

According to Durant, “Without a doubt, I owe my life to those two men and their bravery. Those guys came in when they had to know it was a losing battle. If they had not come in, I wouldn’t have survived.” Gordon and Shughart were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on May 23, 1994.

Navy Capt. William McGonagle, Eastern Mediterranean

Wikimedia Commons

When McGonagle received the Medal of Honor, it was not done in standard fashion. In fact, the medal was presented by the Navy secretary in a secluded part of the Navy shipyard near Washington.

McGonagle was in command of the USS Liberty in 1967 when it was attacked by Israeli forces. The Liberty was an intelligence gathering ship sent to the Mediterranean by the National Security Agency to spy on Soviet pilots.

One day, for no foreseeable reason, Israeli fighter jets and attack ships converged on the Liberty. The ship was “in international waters, properly marked as to her identity and nationality, and in calm, clear weather when she suffered an unprovoked attack,” according to an official report. Machine gun fire, rockets, napalm and torpedoes rained down on the Liberty. One torpedo even tore a 40-foot hole in the ship, according to a report.

McGonagle, on the bridge, was severely injured from shrapnel and napalm burns. Even so, he refused medical attention so he could maintain command of a badly beaten ship. McGonagle said his crew is what inspired him to stay despite profusely bleeding. “I would lay down on the deck, and put my leg on the captain’s chair to stem the loss of blood,” he said. The captain stayed at his post the entire time, navigating by using the North Star so he could lie down.

Finally, 17 hours after the initial attack, U.S. forces arrived to help. Israel later apologized for the attack, saying it was a case of mistaken identity. But survivors have maintained the attack, which killed 34, was deliberate. McGonagle died March 3, 1999, at 73 years old.

Army Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez, Vietnam War

AP Photo

In May 1968, 12 special operators were sent deep into the jungle to gather information on enemy movement. Helicopters dropped the team into the dense forest, but quickly after beginning their patrol, they met heavy resistance. The radios lit up, “Get us out of here!”

Benavidez was at a nearby base and is said to have volunteered to rescue the special operators without anyone asking. “I’m coming with you,” Benavidez screamed as he raced toward the helicopter preparing to launch a rescue mission. He didn’t even bring his M16, only a bowie knife, according to reports.

The special operators were surrounded. Benavidez grabbed his medic bag and jumped out of the helicopter, racing toward the wounded men. Before reaching them, he took a bullet in the leg and shrapnel to the face. Continuing on, he reached the troops and started to dress wounds and hand out ammunition. He then called in “danger close” airstrikes. As the battle progressed, Benavidez was coughing blood. A soldier reportedly asked him, “Are you hurt bad, Sarge?” He replied, “Hell no.”

When the rescue helicopter landed, Benavidez famously said to his fellow soldiers, “Pray and move out.” Benavidez took seven major gunshot wounds, 28 pieces of shrapnel, and both arms had been slashed. Benavidez was told that his one-man battle was extraordinary. He replied, “No, that’s duty.” After years of bureaucracy, Benavidez was presented with the Medal of Honor Feb. 24, 1981. He died Nov. 29, 1998, at 63.

Air Force Capt. John Walmsley, Korean War

Wikimedia Commons

Walmsley was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for the daring risks he took to drop bombs on targets during the Korean War. Walmsley, a former flight instructor, piloted a B-26 belonging to the 8th Bombardment Squadron. He was developing strategies for searchlight attacks against enemy convoys.

Korea was resupplying its army overnight through truck and train convoys. One night, Walmsley discovered an enemy supply train near Yankgdok, Korea, as he flew over. This train was a high value target, according to a report. Walmsley identified and dropped bombs on the train, eventually running out. The train, as a result, was disabled.

Instead of returning to base, Walmsley called for more friendly aircraft to complete the destruction of the train. While flying, he used his searchlight to expose the train. This, however, made him an easy target for the enemy. Walmsley made two low-level passes over the top of the train to guide the other B-26s. Before he could complete another pass, his plane took enemy fire. The damage to the aircraft was catastrophic and he crashed into the mountains nearby. Walmsley was a combat veteran and had already completed 25 combat missions. His courageous actions allowed his comrades to continue the fight even at the cost of his own life. Walmsley was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor June 12, 1954.

Navy Rear Adm. Richard Nott Antrim, World War II

Antrim earned the Medal of Honor for his bold actions in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Then-Lt. Antrim, the executive officer of the USS Pope, was taken prisoner when the Japanese sunk his ship. Antrim was the senior most surviving officer.

While in Japanese custody, the allied prisoners received brutal punishment for breaking petty rules. One day in April 1942, Antrim witnessed a fellow prisoner being sentenced to 50 lashings for not bowing to a guard. After 15, the man was unconscious. Antrim then offered himself to be beaten in place of his unconscious comrade, stepping forward and saying, “I’ll take the rest,” according to a report. Silence ensued at the compound and Antrim repeated, “I’ll take the lashes.” A loud roar erupted from the prisoners and the Japanese didn’t know what to do.

The Japanese officer in charge saluted Antrim for his selfless disposition. From that moment on, the Japanese ceased harsh punishments and a new level of respect for the men who were taken prisoner from the battlefield emerged. Antrim, along with the other prisoners, was released August 1945 at the end of the war. For his heroism, President Truman awarded Antrim the Medal of Honor in 1947. The admiral died on March 7, 1969, at age 61.

Marine Lt. Col. Ernest Williams, Dominican Republic Occupation

Williams earned his Medal of Honor during the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic. He was the leader of a 12-man force tasked with overtaking an enemy fortress that was holding hostages.

As Williams’ team rushed the compound, eight were hit by rifle fire. He pressed on with the four remaining men. Williams threw himself into the door of the fortress just as an enemy soldier was closing it. He forcefully barged in and started firing at the guards inside. Williams narrowly escaped death from a rifleman and continued on to find the hostages.

It only took a few minutes for Williams and his men to gain control of the fort and the 100 prisoners kept hostage there. Williams’ brave act to put the prisoners before him earned him distinction. He died on July 31, 1940.

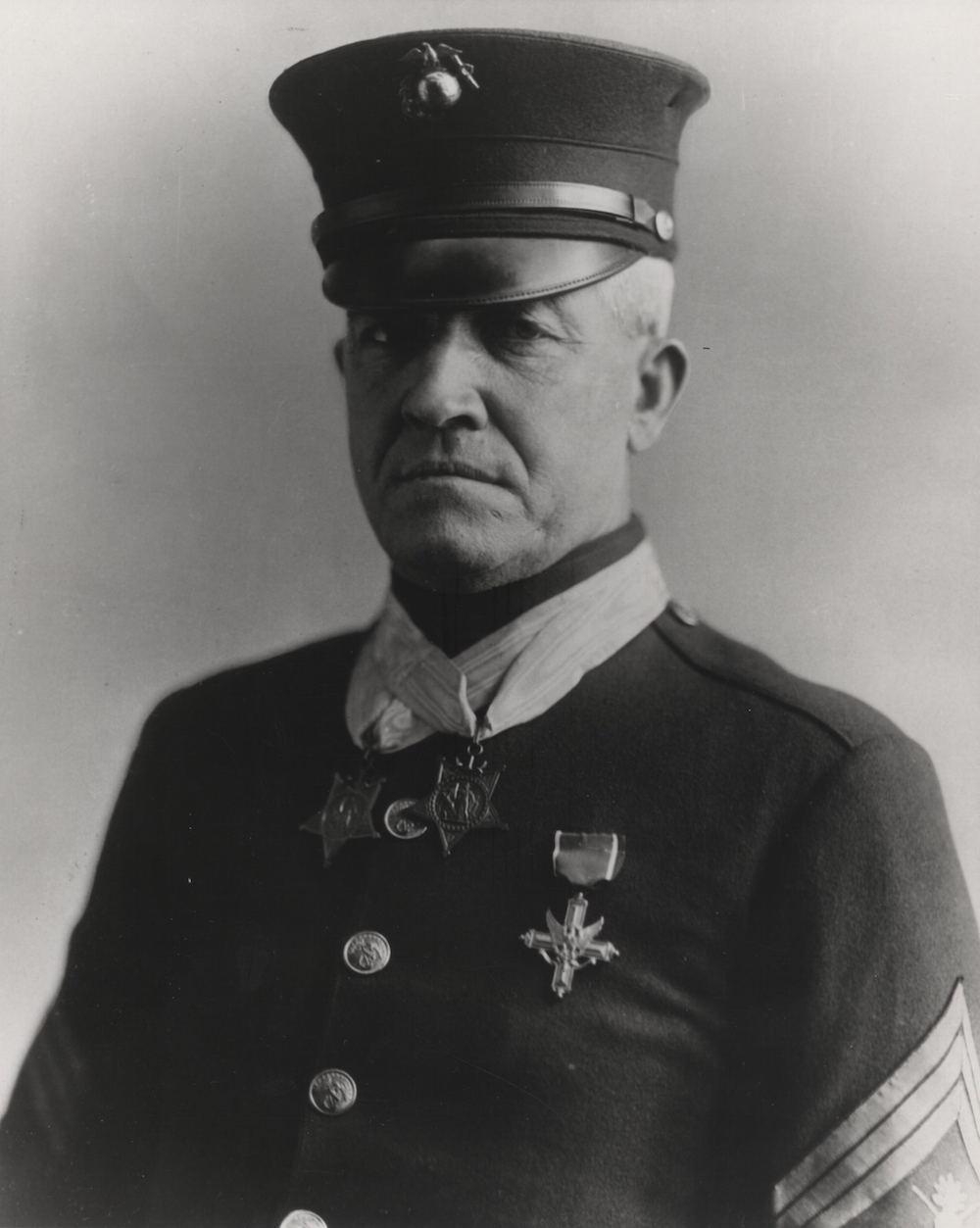

Marine Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler, Invasion of Haiti

AP Photo

Butler, in his second action to be awarded a Medal of Honor, led an attack against a Cacos compound in Haiti in October 1915. Butler had already been ambushed by 400 Cacos and was setting up a 700-Marine attack. The attack was successful and cleared all Cacos except a small compound.

A team of about 100 Marines and sailors were put under Butler’s command to mount an attack against the fort. On Butler’s order, the team surrounded the fort and engaged the Cacos in hand-to-hand combat. The entire battle lasted 20 minutes. Only one Marine was wounded and 51 Cacos’ were killed.

Butler received his first Medal of Honor Dec. 4, 1915 for his actions in Vera Cruz and a second Medal of Honor the following year for his actions against the Cacos. He continued serving in the Marines for 16 more years and died June 21,1940 at age 58.

Army Cpl. Sidney Manning, World War I

Manning was on an assault on a fortified position overlooking the Ourcq River in France in July 1918. During the assault, Manning’s platoon commander and sergeant took casualties, leaving him in command.

While severely wounded, he led the remaining 35 men to gain an advantage on the enemy. Ruthless in his pursuit, Manning led his soldiers forward. Finally, after gaining the upper position on the enemy, Manning realized that only seven of his original 35 men remain alive. The enemy was now only 50 meters away. Manning’s platoon consolidated as he held off the enemy. He refused to take cover until his remaining soldiers did so.

Manning suffered a total of nine wounds in the battle but survived. His courage and leadership through the mid-summer battle earned him the Medal of Honor Dec. 31, 1919. Manning died Dec. 15, 1960 at age 68.

Marine Gen. Christian Schilt, Nicaragua Occupation

Wikimedia Commons

Schilt was one of the first Marine Corps aviators ever when he selflessly evacuated fellow Marines from a harsh combat zone in 1928.

Then-Lt. Schilt, in the midst of a Nicaraguan civil war, got word that two Marine patrols had been attacked by rebels. The Marines were cut off and unable to be resupplied. With no landing strip for an airplane around, the Marines had to burn down part of the town.

Over three days, Schilt voluntarily made 10 separate flights into the hostile area. Schilt and his Corsair biplane had to overcome “hostile fire on landings and takeoffs, low-hanging clouds, mountains, and tricky air currents,” according to a report. His flying ability those three days are described as “almost superhuman skill combined with personal courage of highest order.”

Schilt’s efforts to resupply the troops, evacuate 18 wounded Marines, and bring in a relief commanding officer directly led to three lives being saved. He was awarded the Medal of Honor July 9, 1918 and went on to serve a distinguished 40-year career in the Marine Corps. Schilt died Jan. 8, 1987, age 91.

Marine Sgt. Maj. Dan Daly, Boxer Rebellion

Wikimedia Commons

Sgt. Maj. Dan Daly and Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler are the only double recipients of the Medal of Honor. At 5 feet, 6 inches and 132 pounds, Daly was a force to be reckoned with. His actions responding to the Boxer Rebellion earned him his first Medal of Honor.

Daly was deployed on the USS Newark when they got the call. Marines were inbound to China because a secret organization called the Boxers had declared war on China and all countries with diplomatic ties. Once in China, the Marines took up positions along the wall of the consulate. As the Marines disembarked the ship, they started to go back for supplies, leaving Daly as the sole Marine on guard.

Shortly after, the Boxers realized Daly was the only one at the consulate and attempted a strike. The Boxers thought they had an easy shot at Daly, but they were sorely mistaken. The next morning, when the other Marines returned, there were 200 enemy bodies scattered on the ground.

Daly received his first Medal of Honor in 1901 for actions in the China Relief operation. He continued serving in the Marines, earning a second Medal of Honor in 1915 during the U.S. Haiti occupation. Daly died April 27, 1937 at the age of 63.