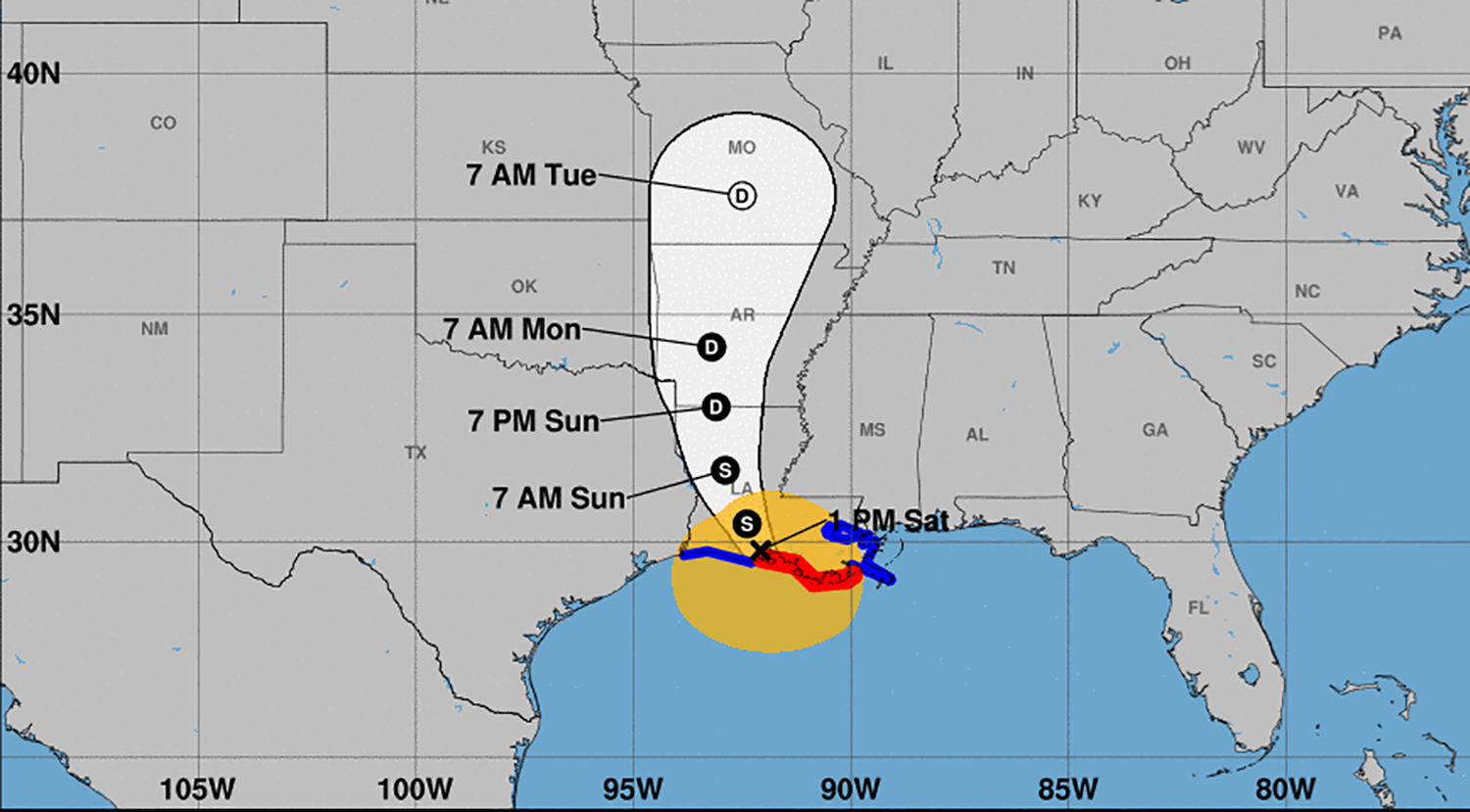

Hurricane Barry made landfall west of New Orleans midday Saturday, bringing with it a high-risk flooding event that could last for days in southern Louisiana.

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards said the slow-moving hurricane made landfall during a news conference at around 1:45 p.m. Moments later, the National Hurricane Center confirmed the landfall near Intracoastal City and announced an immediate downgrade to tropical storm strength.

Yet the stormy weather and the risks associated with it are from over. “I want to caution everybody. This is just the beginning,” Edwards said.

Barry was a hurricane for roughly three hours. The National Hurricane Center made that call just shy of 11 a.m. ET, determining the maximum sustained winds were 75 miles per hour, as the Category 1 hurricane was only dozens of miles south of the coast. Barry was the first named hurricane of the Atlantic hurricane season.

#Barry made landfall as a hurricane early this afternoon near Intracoastal City, LA. Although the center is now over land, the rainfall threat is just beginning for many locations. Continue to follow updates at https://t.co/tW4KeGdBFb and https://t.co/SiZo8ozBbn pic.twitter.com/2IFyKGpHtb

— National Hurricane Center (@NHC_Atlantic) July 13, 2019

Among its hazards are life-threatening storm surge to coastal areas of Louisiana and Mississippi, heavy rainfall and flash flooding, and strong wind and the threat for downed trees and power lines, according to the National Weather Service. Tornadoes are also possible. Over the next couple days Barry will continue to weaken and dissipate as it rolls through Arkansas and Missouri.

Flooding remains a significant concern as the ground is already saturated in places such as New Orleans, the streets of which flooded due to heavy rain on Wednesday. The National Hurricane Center said up to rain accumulations are expected to be 10 to 20 inches in south-central and southeast Louisiana and southwest Mississippi, and 25 inches of rain could fall in some isolated areas.

The weather event will be a major test for levees along the Mississippi River, some of which have a height as low as 20 feet. New Orleans officials have urged residents within the protection of city levees to stay home and hunker down rather than flee the city, though other towns in Louisiana such as Grand Isle opted for mandatory evacuation on Thursday afternoon. Floodgates in New Orleans were all closed by Friday evening as the National Weather Service issued a hurricane warning for the area.

By the afternoon, some levees not along the Mississippi River were being overtopped due to high water.

VIDEO: Per Plaquemines Parish officials, water has overtopped the back levee at Myrtle Grove and Pointe Celeste.

One homeowner nearby shared this 10AM view of the rising waters ahead of #TropicalStormBarry. #NBCNews pic.twitter.com/jNkzMXJrEV

— Morgan Chesky (@BreakingChesky) July 13, 2019

In Lafourche Parish, video from the South Lafourche Levee, posted by the local sheriff’s office, showed Louisiana Highway 1 flooded on Saturday.

VIDEO: View of LA 1 from the South Lafourche Levee. Video provided by Golden Meadow Police Chief Reggie Pitre. #TropicalStormBarry pic.twitter.com/lJRQoOFEpe

— Lafourche Parish Sheriff’s Office (@LafourcheSO) July 13, 2019

Water also appeared to rise above a levee in St. Mary Parish, near where Barry made landfall. Parish President David Hanagriff issued a mandatory evacuation for some residents and deputes went around knocking on doors to let people know as the water level rose.

REPORT: possible flow overtop levee in St Marys Parish bear Midway LA from Hwy 317 at 330 pm. Residents evacuating north @accuweather @breakingweather @NWSNewOrleans pic.twitter.com/59I9IbKIO4

— Reed Timmer (@ReedTimmerAccu) July 13, 2019

Last week Governor Edwards said the levees would likely not be topped by storm surging. He did, however, share concerns that floodwaters would be substantial, saying, “This is going to be a major rain event across a huge portion of Louisiana … Look, there are three ways Louisiana floods — storm surge, high rivers, and rain. We’re going to have all three.”

UPDATE: tree damage, power lines down across Morgan City, LA from #HurricaneBarry including this large tree crushing a vehicle. Thankfully no one was inside. This shows you one of the many dangers with going outside during a hurricane @breakingweather @accuweather pic.twitter.com/yzvxUPJ0bF

— Reed Timmer (@ReedTimmerAccu) July 13, 2019

Scary. Hurricane Barry tearing off a roof in Morgan City, Louisiana.?Maria Martinez @WGNOtv @HankAllenWX @StormHour @NWSNewOrleans @NWSLakeCharles pic.twitter.com/wjaN1dshjb

— Scot Pilie’ (@ScotPilie_Wx) July 13, 2019

More than 1000,000 Louisiana homes and businesses lost power even before the storm made landfall and the Coast Guard rescued 12 people, including some on rooftops, and a cat from Island Road in Cocodrie, Louisiana, was also rescued this morning. They were flown to a shelter in Houma, Louisiana.

#GOESEast watches as #HurricaneBarry, now a Cat. 1 storm, creeps toward southern Louisiana. Dangerous storm surge, heavy rains and high winds are already impacting the north-central Gulf Coast. Latest updates: https://t.co/1L8q1zg4eW pic.twitter.com/wqI2lr8c83

— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) July 13, 2019

Most flights in and out of Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport and Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport have been scrubbed.

The Louisiana National Guard has mobilized more than 2,500 of its Army and Air Guard members to respond to the storm. President Trump declared a state of emergency for Louisiana on Friday in advance of Barry’s impact, freeing up federal assistance to local response efforts.

Barry’s landfall comes nearly 14 years after Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana as a Category 3 major hurricane, overwhelming levees around New Orleans and creating a flooding disaster in the Big Easy. New Orleans constructed a $14 billion flood-mitigation system, comprised of a network of levees and floodwalls, after Katrina’s devastation killed more than 1,800 people in 2005.

Also at risk this weekend are the constellation of oil and gas rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, many of which are shutting off production and have been evacuated. Energy prices have already begun to surge in some places as a result.

The National Hurricane Center began tracking the area of low pressure sweeping over several southeastern states towards the warm waters of the gulf earlier this week. Forecasters colloquially called this a “home brew” system, as it developed over the waters of the gulf near the U.S. as opposed to off the west coast of Africa, which is not uncommon in the early part of the hurricane season.

Up until now, it has been a rather quiet Atlantic hurricane season, which officially began on June 1. There has only been one other named storm so far, Andrea, which formed into an organized tropical system in May south of Bermuda and quickly petered out.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is the parent agency of National Hurricane Center, predicted in May that the Atlantic hurricane season would be near-normal in 2019. They also predicted there would likely be between nine and 15 named storms with winds of 39 mph or higher, four to eight that could become hurricanes with winds of 74 mph or higher, and two to four major hurricanes that are Category 3, 4, or 5 storms with winds of 111 mph or higher.

The outlook reflected two “competing climate factors” this year. “The ongoing El Nino is expected to persist and suppress the intensity of the hurricane season. Countering El Nino is the expected combination of warmer-than-average sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, and an enhanced west African monsoon, both of which favor increased hurricane activity,” the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said.

In the Pacific Ocean, there has been a little more activity with three named storms, including Barbara, which had been a powerful Category 4 hurricane but dissipated and the remnants of which brought some soggy weather to Hawaii.